The HemeChip Detects Sickle Cell And Other Blood Diseases In A Flash, May Help Developing Nations

It’s no bigger than a credit card, but it may someday save the lives of countless infants in struggling nations.

At the 57th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology (ASH) Monday, a team of researchers, hailing primarily from Case Western Reserve University (CWRU) in Cleveland, Ohio, presented their ongoing work on a mobile device capable of detecting a number of genetic blood disorders — including sickle cell disease — in a much more efficient fashion than conventional tests available currently. Aptly called the HemeChip, the device would enable formerly undiagnosed infants to receive the prompt medical care they’d need early on, preventing later health complications and even death.

"While sickle cell newborn screening is standard in the U.S., very few infants are screened in Africa because of the high cost and level of skill needed to run traditional tests," explained project researcher Dr. Little, Associate Professor at the CWRU School of Medicine, in a statement. "This new mobile technology provides an easy to use, cost-effective tool that takes us closer to standardizing newborn screenings on mobile devices, thus simplifying diagnosis. It could make a huge difference in developing nations worldwide, enabling early treatment for this disease." Little is also Director of the Adult Sickle Cell Anemia Program at the Seidman Cancer Center of University Hospitals, which is affiliated with CWRU.

A Chip Off The Old Block

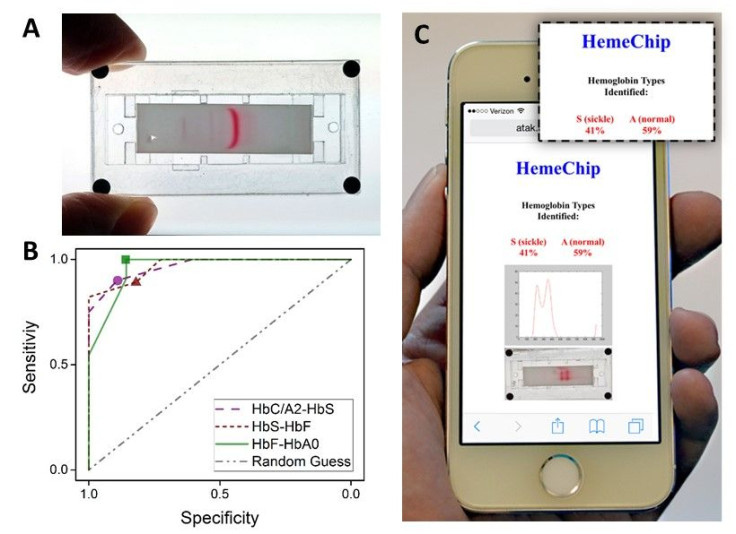

Hemechip uses a battery-powered technique known as cellulose acetate electrophoresis to identify a person’s varying types of hemoglobin, a protein that helps red blood cells transport oxygen throughout the body.

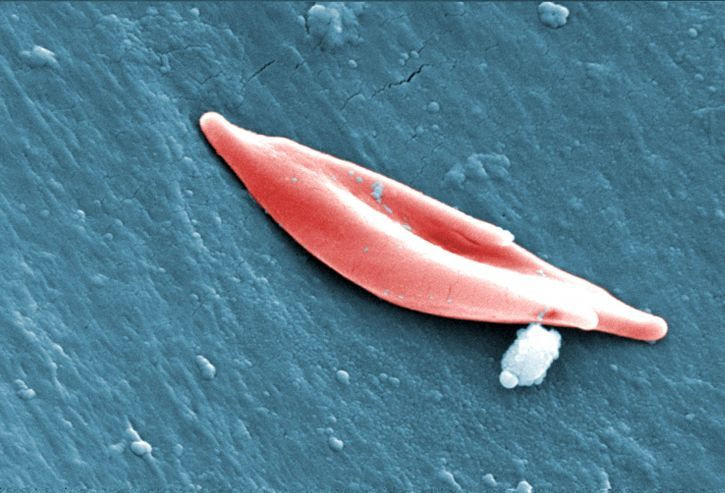

People with sickle cell disease (SCD) possess two copies of a gene that makes their body produce defective hemoglobin (HbSS), which in turn creates abnormally shaped red blood cells. Shaped like a crescent, these cells often get stuck in the bloodstream or quickly die off, regularly depriving the body of oxygen and causing fits of pain, fatigue (anemia), and other chronic issues. Those with only one copy of the sickle-cell gene have sickle cell trait (SCT), and while they usually have few health problems, their hemoglobin is noticeably different as well (HbAS).

Depending on how far the hemoglobin from a blood sample travels along the HemeChip, the user can easily tell whether someone has SCD, SCT, or a milder form of SCD caused by having one copy of the sickle cell gene and a copy of another hemoglobin mutation (HbC).

In previous versions of the project, which has won several awards, including the 2015 Student Healthcare Technology Prize, HemeChip was able to obtain test results in less than 30 minutes, while requiring no more than a finger prick’s worth of blood, and its building materials added up to less than $5. In the paper presented Monday, the device’s accuracy was comparable with existing testing methods and it is now able to transmit the results to a smartphone or similar device via cloud computing in an easy to understand format.

The importance of something like HemeChip is hard to overstate, with the project members citing research from the World Health Organization stating that 70 percent of deaths attributable to SCD in Africa could have prevented with early detection and medical intervention. It’s estimated that over 6 million people alone in West and Central Africa currently have SCD.

For the next step in HemeChip’s development, the project researchers will look to travel to Ghana to test out their device in the real world.

Source: Ung R, Alapan Y, Noman Hasan M, et al. Point-of-Care Screening For Sickle Cell Disease By a Mobile Micro-Electrophoresis Platform. 57th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology. 2015.

Published by Medicaldaily.com