History Of Autism And Vaccines: How One Man Unraveled The World’s Faith In Vaccinations

Vaccination rates plummeted and infection rates of preventable diseases skyrocketed when the world started to believe vaccines caused autism, but the rapid rise of autism rates tell a different story. An infographic has been designed to inform parents and other skeptics of the truth behind the relationship between vaccinations and autism and why it even started in the first place.

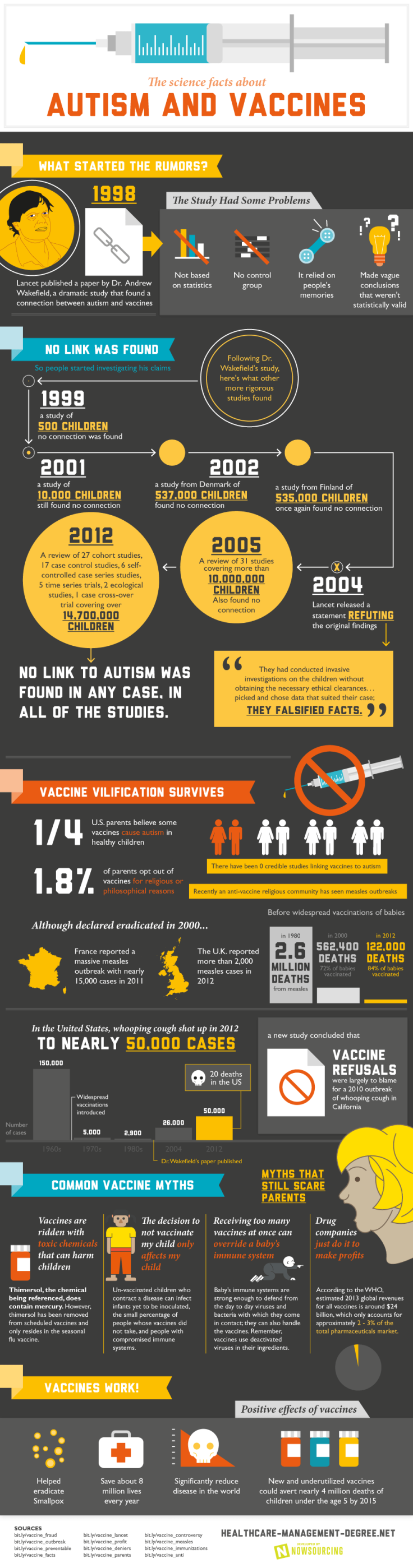

Why did people begin thinking that childhood vaccines such as the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) shots, cause autism? The birth of this falsehood was fathered by Dr. Andrew Wakefield, a British surgeon and medical researcher who published a study in The Lancet in 1998 claiming to have found a connection between vaccines and the onset of autism.

Autism is a brain development disorder that causes social, cognitive, and communication impairements. It can range from very mild to very severe and does not discriminate by ethnicity or socioeconomic groups, as it can happen to any child. Currently, research points to a genetic predisposition of autism in addition to an environmental component. The sharp rise in autism diagnosis over the last 20 years cannot be attributed solely to genetics, so research presses on, according to the National Autism Association.

When the paper was published it spread like wildfire across the world, instilling fear in parents and pediatricians alike. But after a decade-long investigation of unraveling Wakefield’s research and studies of 25,782,500 children, researchers concluded there was no causal relationship between vaccines and autism. Wakefield’s paper was retracted in 2010 due to the paper’s scientific limitations, which were not based on statistics, lacked a control group, relied on people’s memories for vaccination records, vague conclusions not based on statistical outcomes, and the use of such a small group of 12 children as test subjects.

Researchers scrambled to find the answer, and by 1999 they had conducted a study using 500 children. No connection between autism and vaccines was found. But just to make sure, scientists went back to the drawing board and two years later another study was published using 10,000 children. Studies using 537,000 children were evaluated in Denmark, and then an additional 535,000 children were studied in Finland. Not only could no one reproduce Wakefield’s findings, but they couldn’t even find a link anywhere in their own research.

In 2012, a meta-analysis was conducted using 14,700,000 million children. No link to autism was found in any of the 58 studies researchers analyzed, yet the leftover of Wakefield’s small but dramatized findings have left millions of children unvaccinated.

Today, one out of four parents believes vaccines cause autism in otherwise healthy children, and there has consequently been a steady decline in vaccinations. In the past 20 years, vaccines given to infants and young children will prevent 322 million illnesses, 21 million hospitalizations, and 732,000 deaths throughout their lifetime, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Yet, there were nearly 50,000 people in the United States who contracted whooping cough, which caused 20 deaths in 2012 alone. Whooping cough is a highly contagious respiratory tract infection that is completely preventable if a child is vaccinated. Before Wakefield’s paper was published, there were only 2,900 cases throughout the 1980s. It's currently on the rise, and an additional 5,400 children in California were reported to have confirmed whooping cough cases as of July 8.

There are new and underutilized vaccinations waiting to treat children, if only their parents were informed enough to understand they’re non-threatening. They have the power to prevent nearly four million deaths of children five years and young by 2015.

Published by Medicaldaily.com