How Does A Blood Transfusion Change Your Body And DNA?

It can be an icky thought to imagine someone else’s blood flowing through your own veins. Blood is one of the bodily fluids through which all sorts of diseases can be transmitted. And adding to the weird factor, blood carries a person’s DNA, the signature that is supposed to be unique to their body.

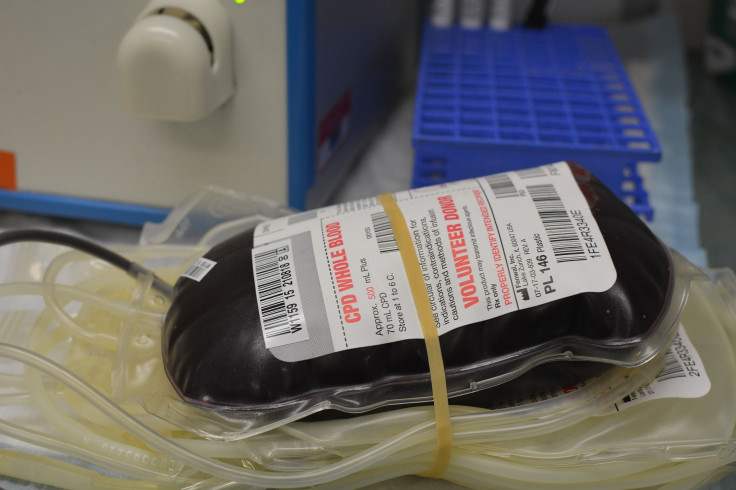

But when it’s life or death, another person’s blood could be the only option. Transfusions are a common procedure. The U.S. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute notes that about 5 million Americans get one every year — either a transfusion of the whole blood or just certain parts of it, like platelets, plasma or red or white cells. That could be due to injuries or surgeries that cause blood loss; bleeding disorders like hemophilia in which the blood does not clot properly; infections that inhibit the body’s ability to make blood; and other illnesses, like anemia, cancer and autoimmune disorders.

Although scientists in Singapore have recently found a way to turn skin cells into blood cells in mice, that method has yet to be tested on humans. With the exception of some people who can donate blood ahead of an elective surgery to then be transfused back into their bodies afterward, the blood will come from a kind-hearted donor. The good news is you will continue being yourself after receiving donor blood — even if you have a little of the other person mixed in.

Scientific American explains that when donor blood is mixed into the body with a transfusion, that person’s DNA will be present in your body for some days, “but its presence is unlikely to alter genetic tests significantly.” It is likely minimized because the majority of blood is red cells, which do not carry DNA — the white blood cells do. That publication notes studies have shown that highly sensitive equipment can pick up donor DNA from blood transfusions up to a week after the procedure, but with particularly large transfusions, donor white blood cells were present for up to a year and a half afterward. Still, even in those latter cases, the recipient’s DNA was clearly dominant over the donor DNA, which is easily identifiable as “a relatively inconsequential interloper.”

The real risks from a blood transfusion come from the body’s reaction to the strange blood. The Mayo Clinic lists an allergic reaction, fever, an overload of iron in the body, or a serious but rare condition in which the white blood cells of the donor blood attack your bone marrow, a form of graft-versus-host disease. “It is more likely to affect people with severely weakened immune systems, such as those being treated for leukemia or lymphoma,” the organization says. It is also unlikely for the donor blood to be carrying an infection, as blood banks screen for those, but in extremely rare cases it may transmit HIV or hepatitis.

To learn more about blood donation, visit the New York Blood Center or the American Red Cross.