How Exactly Does Cancer Spread? Researchers Learn To Trigger Metastasis

Cancer cells that stay in one place can often be targeted and removed. Most of the 580,000 cancer deaths in the United States happen because the cancer has spread to other parts of the body in a deadly process called metastasis.

Now researchers in New York City have come closer to understanding what causes cancer migration. By using new observation techniques and by tweaking genetic commands, they essentially turned on and off a key protein in metastasis called Rac1. The findings, published Sunday in the journal Nature Cell Biology, offer fresh hope that new drugs could someday shut down the spread of cancer.

"Rac1 inhibitors have been developed, but it wouldn't be safe to use them indiscriminately," says Yeshiva University's Dr. Louis Hodgson, who led the study, in a statement. Their research was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

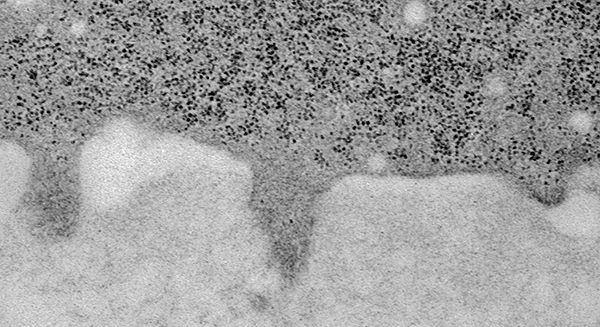

The actual mechanisms for cancer migration are little protrusions from cancer cells called invadopodia — invasive feet. These nubs stick out into the space between cells, releasing an enzyme that destroys the intercellular material and pulling the cell toward blood vessels. Floating through the blood stream, cancer can easily reach other parts of the body.

If invadopodia are the foot soldiers, Rac1 is the general telling them what to do. But until this study, according to Yeshiva University, no one had actually seen Rac1 in action. To understand the protein's role, the researchers deployed a fluorescent biosensor, like protein dye, on invasive breast cancer cells taken from humans and mice. With it, they could watch "exactly when and where Rac1 is activated inside cancer cells," the university said.

What they saw turned previous beliefs about Rac1 on their heads. Before, scientists thought increased amounts of the protein caused more cancer invasion. In fact, the opposite is true: When invadopodia were most active, there was less Rac1 in the cells. Higher Rac1 levels turned off the invadopodia.

Hodgson and his team tested their observations through genetic manipulation. As with any protein, DNA sequences in cancer cells order the creation of Rac1. When the researchers silenced those sequences, Rac1 levels dropped, and the cancer spread faster. Hodgson says this new knowledge will be vital for drug development.

But there's still a long way to go; you can't just turn off all the Rac1 genes in a cancer patient's body. "Rac1 is an important molecule in healthy cells, including immune cells," Hodgson says. "So we'd need to find a way to shut off this signaling pathway specifically in cancer cells."

Source: Hodgson L, Condeelis J, Miskolci V, Bravo-Cordero J, Moshfegh Y. A Trio-Rac1-Pak1 Signalling Axis Drives Invadopodia Disassembly. Nature Cell Biology. 2014