How Fecal Microbiota Transplants Boost Healthy Gut Flora And Fight Infections

Fecal transplants are essentially a donor’s feces mixed with a saline and placed into another patient by colonoscopy, endoscopy, or enema. It sounds gross, but it’s a ground-breaking therapy that cures people of a severe gut infection caused by the bacteria Clostridium difficile, which causes C. diff. colitis and debilitating diarrhea.

Fecal microbiotica transplants (FMT), also referred to simply as fecal or stool transplants, are meant to restore the good or “healthy” bacteria in a patient’s gut after they’ve been overthrown by sickness or the destructive effects of antibiotics. Ironically, though antibiotics are meant to kill bad bacteria, they end up destroying good bacteria in the stomach as well, which can pave the way for a C. diff. colitis infection. While fecal transplants aren’t very well known or used that often, they have a 90 percent success rate with little to no side effects.

“After months on antibiotics, it is amazing to see how quickly a fecal transplant can help people,” Dr. Bret Lashner, a gastroenterologist at the Cleveland Clinic, writes on HealthHub. “In my practice, I have performed eight of these procedures to date. So far, there has been an excellent success rate and those that respond do so within two weeks. It is a therapy that works.”

The Donor Prepares

Before the procedure can take place, the patient needs to find a donor: a friend or relative who’s willing to donate a sample of their stool. First, the donor must be tested for Hepatitis A, B, and C; as well as the HIV virus, syphilis, and parasites. They must also not have taken antibiotics for up to three weeks before the transplant, not have chronic diarrhea, inflammatory bowel disease, or colorectal cancer, and not have any sexually-transmitted diseases.

As preparation, the donor has to take a capful of Miralax (a laxative) before they go to bed the night before in order to help get their bowels moving. In the morning, they’ll collect a “fistful-sized amount of the stool in a ‘hat’” from a pharmacy, according to the Cleveland Clinic. This must then receive 500 cc of saline, then be dissolved as much as possible in a blender. Afterwards, the mixture must be filtered through a coffee filter to eliminate any particles, poured into a plastic container and kept cold in a cooler until it arrives to the endoscopy unit. This mixture has to be used within 6 hours in order to be useful.

The Patient Prepares

The recipient must also be tested for Hepatitis, HIV, syphilis, and parasites; then they have to simply follow a typical preparation for a colonoscopy. This involves making sure you’ve completely cleaned out your colon and rectum – and in order to do that, you’d need to follow a special diet the day before (no solid foods, only clear liquids like plain water and tea). Patients may be asked to avoid eating anything after midnight the night before the exam, and also will need to take laxatives the day before and the morning of as well. Once the patient arrives at the endoscopy unit, they’ll take two loperamide tablets to help slow digestion.

The Procedure

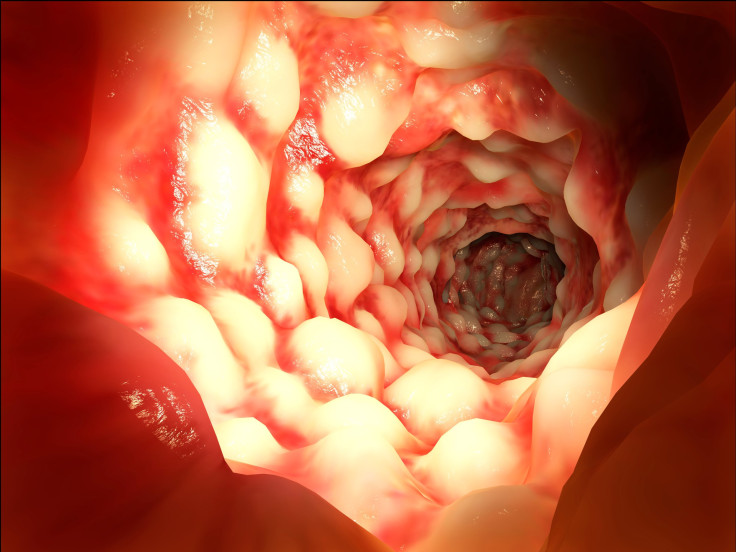

First, the doctor will insert an IV into your vein to pump sedatives and fluids into your body. The fecal transplant is typically carried out by a colonoscopy: a process that allows the doctor to view the insides of your large intestine, which includes your rectum and colon. Colonoscopies are used to check on your innards, making sure you don't have ulcers, colon polyps, tumors, or internal bleeding in your intestines.

In the fecal transplant, however, instead of carrying a camera through your intestines the way a colonoscopy does, the procedure involves the colonoscope entering then being withdrawn, which releases the donor stool into the colon.

The Aftermath

The procedure, overall, is quite simple. And once you've recovered from the sedatives (and have someone drive you home), all you have to do is rest to feel better.

Some patients go through several rounds of antibiotics before their bacterial infection is so severe that they have no other choice but to undergo a fecal transplant; but nearly every case is successful and in some, life-saving. Whereas antibiotics are sometimes ineffective and even damaging (ironically causing infections in some cases due to bacterial imbalances in the gut), fecal transplants, however strange-sounding, can cure them.