Huguette Clark, Copper Heiress, Leaves Money To Hospital, Nurse: What Defines An Appropriate Caregiving Relationship?

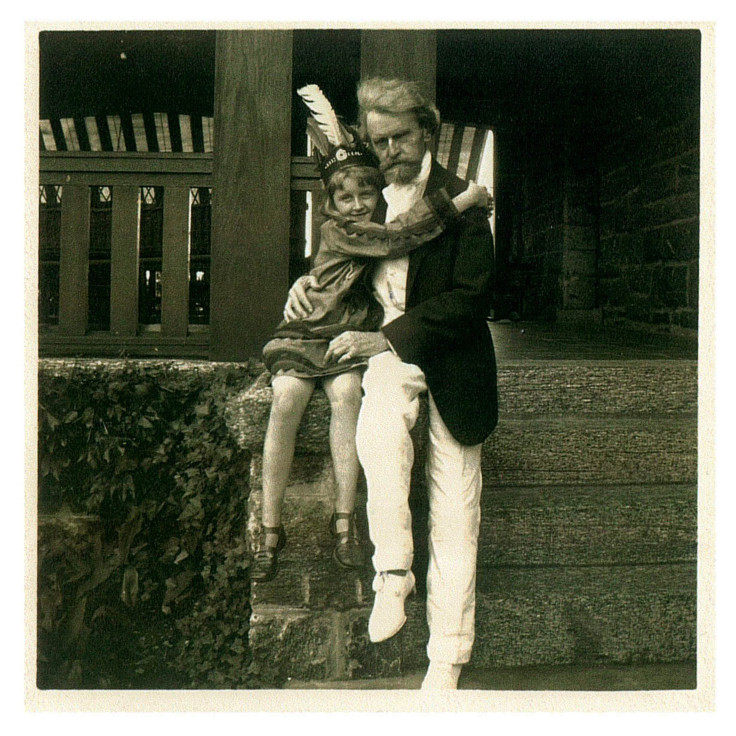

Jury selection is due to start tomorrow in a civil trial disputing the will of Huguette Clark, a childless and reclusive heiress who died in 2001 at age 104. She left behind an estimated $300 million, all of which she inherited from her father, Senator William A. Clark, who made his fortune from copper mines, a railroad, and land sales. According to the New York Times, her would-be heirs are all half-relatives, the descendants of her father and his first wife.

Meanwhile, her intended heirs are her caregivers and the hospital where she lived. Although she owned a 42-room Manhattan apartment, an oceanfront mansion in California, and a 52-acre estate in Connecticut, Clark died in a hospital room at Beth Israel Hospital where she had lived in good health since 1991. After receiving treatment at that institution for advanced skin cancer and malnutrition, her doctors advised her to return home. Instead, she insisted on staying and paid $400,000 a year outright to do so.

She also paid an enormous amount in gifts. The Boston Globe reports that her nurse, Hadassah Peri, has already received nearly $31 million in cash, presents, and property, and she may get $30 million more if Clark’s will is upheld. The disputed will also signifies her primary physician, Dr. Henry Singman, as the beneficiary of $100,000, though he plans, according to the Boston Globe, to relinquish this before testifying at the trial. That said, Clark has reportedly already given him $500,000 or more in cash, covered some of his own medical expenses, and paid part of his granddaughter’s college tuition. Additionally, Beth Israel received a $1 million bequest, a multimillion-dollar painting by Edouard Manet, and hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash gifts from Clark.

The Real Story?

In an excerpt from Empty Mansions by Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr., the authors offer the painful details of Clark’s nearly 20 years in the hospital. She entered a frightened and lonely recluse with skin cancer of her face that was so bad she could not hold food in her mouth. In her first days, she wrapped herself in sheets like a homeless person, according to an excerpt published in Business Insider. After receiving appropriate care, Clark was rarely sick and required no daily medications other than vitamins.

The case raises many questions, including, what constitutes appropriate and ethical behavior on the part of caregivers?

In a study published in Health Communications, researchers from the University of Kansas investigated two metaphors frequently used to describe the doctor-patient relationship: paternalism versus consumerism. Paternalism focuses on obligations, assumes the doctor is beneficent, and implies trust, the researchers suggested, while consumerism focuses on rights, assumes the doctor is self-centered, and replaces trust with accountability. Whereas paternalism assumes that principles of good medical care override individual treatment preferences, consumerism presumes that the patient's own values dominate. According to the authors, paternalism also assumes that third-party intervention is inappropriate whereas consumerism may require such supervision.

“Conflict may develop when doctor and patient approach the relationship using differing metaphors,” wrote the authors.

In the case of Clark and her contested will, the relationship between her and her caregivers seems to blend principles of both consumerism and paternalism. She knew her own mind and made her own decisions, yet her doctors and most especially her nurse, Peri, are claiming they treated her as they would a family member. Peri worked for many years from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., 12 hours a day, seven days a week, 52 weeks a year; she brought soup from home and exchanged loving phone calls late into the night. That said, Peri also received unimaginable gifts from Clark — a Manhattan apartment, among them — that most family members never expect from ailing relatives to whom they give equally extraordinary care.

In the end, a court will be burdened with unravelling the ethical dilemma underlying this unusual relationship between a patient and members of the institution where she died. In doing so, it may very well arrive at a new and more pertinent definition of the caregiver-patient relationship.

Source: Beisecker AE, Beisecker TD. Using Metaphors to Characterize Doctor--Patient Relationships: Paternalism Versus Consumerism. Health Communications. 1993.

Published by Medicaldaily.com