Redemption In Liberia: A Hospital's Painful Recovery From Ebola

The cries of young children ring around the hospital as hundreds of patients, packed tightly together on wooden benches and surrounded by boxes of syringes piled high, wait to be seen.

Nurses shout to be heard as they rush through the dimly-lit corridors, past peeling, faded posters proclaiming 'Ebola is real!' and prompting people to 'Smile!' and 'Say Thanks!'

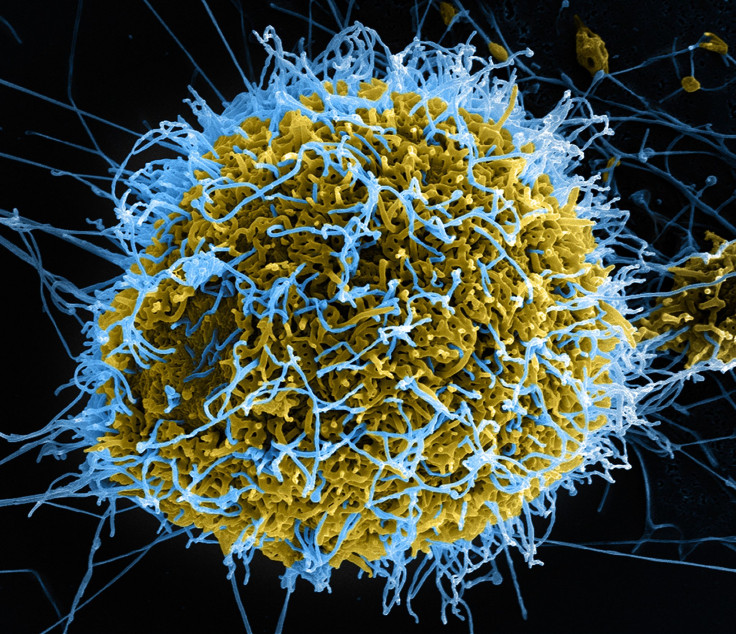

But the patients at Redemption Hospital in Liberia's capital Monrovia have had little to be happy about or thankful for in the wake of the world's worst Ebola outbreak, which has killed 11,300 people in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone since 2013.

The epidemic, which was declared over in Liberia for a third time earlier this month, hit the West African nation the hardest with 4,800 deaths, and ravaged its under-resourced, fragile health system.

Redemption was at the center of Liberia's outbreak, treating the capital's first case of the deadly virus in June 2014, which surged through the hospital, killing 12 doctors and nurses and a string of patients, before forcing the facility to shut down.

"When Ebola struck, we lacked protective equipment, running water was sporadic and there was waste everywhere, said Dominic Rennie, administrator of Monrovia's only free general hospital.

"We had two or three patients in each bed as we wouldn't turn people away... conditions were ripe for Ebola to spread."

The hospital reopened in January last year with a host of reforms - from fewer beds and an Ebola isolation unit to infection prevention measures for staff, such as handwashing and always using and disposing properly of protective gear.

While Redemption and other facilities were revamped as the epidemic ebbed and came under control, the changes may be difficult to sustain in the capital and across the country as vigilance fades and emergency funds dry up, health experts warn.

These improvements could even come at a cost to patients, said Jude Senkungu, a doctor for the International Rescue Committee (IRC).

"The time-consuming triage process (checking patients for Ebola symptoms before admitting them to hospital) could prove fatal for those arriving with critical injuries," he said.

REFORMING REDEMPTION

The Ebola epidemic in Liberia overwhelmed the West African nation's weakened health system, which was slowly recovering after a 14-year civil war that ended in 2003.

Liberia had one of the world's lowest doctor-to-patient ratios - 50 doctors for 4.3 million inhabitants, one for every 90,000 people - before Ebola hit, and spent just $44 per citizen on health in 2013 - half of the average for sub-Saharan Africa.

"Most health facilities were destroyed by the war - Liberia had to start over from scratch," said IRC country director Aitor Sanchez-Lacomba, adding that reconstruction of infrastructure and implementation of basic health services only began in 2010.

In the emergency ward at Redemption, on the site of a former market in a congested slum on Monrovia's outskirts, doctors step over boxes, buckets and stools as they rush between patients.

While the clutter acts as a reminder that the hospital is in transition, it is a far cry from the chaos before and during Ebola, Senkungu said.

"You could barely even move at times as the ward was full of people slumped in chairs, or on the floor, attached to drips."

Redemption stopped receiving inpatients in August 2014 as Ebola swept through the hospital, and became a holding center for suspected cases while a treatment unit was set up nearby.

Most of Redemption closed in October - it continued to admit outpatients with other illnesses, but fear meant few came - to be decontaminated and reformed before reopening in January 2015.

Now, amid the bustle of traders and traffic inching past the hospital entrance, patients are greeted with disinfectant, hand-washing stations, temperature checks and triage - where arrivals are assessed and suspected cases sent to a new isolation unit.

Inside Redemption, the hospital now has 175 beds compared to 215 before Ebola, stocks of gloves, masks and gowns, constant running water, and a new incinerator to dispose of waste.

"Long gone are the days of having more than one patient in a bed or one baby in each crib," said Rennie, with a faint smile.

TURNING PATIENTS AWAY

While Liberia struggled to contain the Ebola epidemic as the number of infected hit 10,000, its response to fresh outbreaks in July and November was vastly improved, health experts say.

"The flare-ups were a huge test for the health system - but they were contained to just a handful of cases each time", said Anouk Boschma, International Medical Corps country director.

Yet alarm was raised in November over the failure to send a suspected Ebola patient directly to a treatment unit, and fears linger over the vigilance of health workers.

"With new measures and protocols, changing old habits and behavior takes time... it is not helped by a lack of mentoring or supervision in health facilities," Boschma added.

A lack of trust from the public presents another challenge, said Pierre Mendiharat from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

The number of Liberians visiting health facilities dipped after the flare-ups, followed by a spike in the number of child patients suffering toxic symptoms due to medication provided by families and traditional healers, the MSF program manager said.

"Fear and mistrust are a huge problem... you need suspected Ebola patients to visit health facilities not only for their own health - but to isolate them so they don't transmit to others."

While many facilities are now stocked with protective equipment and drugs, and staff trained in infection prevention, a transition from emergency to long-term funding means progress may be difficult to sustain, experts say.

At Redemption, a world away from politics and aid issues, Senkungu and his colleagues face a daily struggle to get by.

"We now have to turn patients away, it is upsetting for all of us," he said, walking past a bright blue mural featuring 12 doves - one for each of the hospital's staff who died of Ebola.

"We care for the poorest people in Monrovia, who cannot afford to go elsewhere. What will happen to them?"

(Reporting By Kieran Guilbert, Editing by Ros Russell; Please credit the Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers humanitarian news, women's rights, trafficking, corruption and climate change. Visit www.trust.org)