Local Public Services Less Likely To Answer Emails From People With Black Names

Racism in the United States is rarely as blatant as it once was. Gone, mostly, are the public declarations of hatred towards another person’s characteristics; and when they do occur, they are often shouted down for the incoherent mess that they are.

But discrimination and prejudice — of many different shades — still lingers, hidden in the cracks of our psyche and expressed in far subtler ways. One such way may be in how public servants treat those who ask them for assistance, new research published by the Institute for the Study of Labor suggests.

The researchers, primarily from the University of Southampton in the UK, found that emails sent to over 19,000 local public service providers in the U.S. — which included libraries, county clerks, sheriffs’ offices, and school districts — were more likely to be answered when the sender was clearly identified as white as opposed as black.

In particular, white senders were 15 percent more likely to get a reply back from sheriffs’ offices than their black counterparts. According to the authors, it’s a small but real prejudice that could have lasting negative effects on minority groups who try to interact with these organizations — not to mention patently illegal.

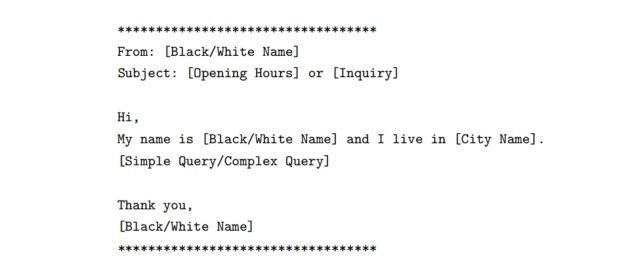

Following in the footsteps of previous experiments, the authors created a base email template that they would then send out to six different types of services run by the local state government — which included county treasurers and job centers in addition to those aforementioned. The email template contained either a simple request (when are opening hours?) to more complicated inquiries (what are the forms needed for school enrollment?), and were signed by one of two names previously known to be seen as clearly white or black. "Jake Mueller" and "Greg Walsh" were the white names, whereas "DeShawn Jackson" and "Tyrone Washington" were used as black names.

“Given a response rate of 72% for white senders, emails from putatively black senders are almost 4 percentage points less likely to receive an answer, they concluded. “We also find that responses to queries coming from black names are less likely to have a cordial tone.”

By less cordial, the researchers meant that black-sent emails were less likely to have the recipient address them by name in the follow-up reply. There was little difference in the success rate between simple and complex emails, though the latter was slightly more likely to be answered.

Of the six providers, only job centers had a similar response rate between blacks and whites, though the racial difference seen in emails sent to county treasurers and clerks was not considered statistically significant. The difference in response rates from school districts, libraries, and sheriffs’ offices ranged from 3.4 to 7 percent. And of the 19,079 providers in total, slightly more than half were school districts.

The authors also sent out a second run of emails that attempted to control for the possibility that those who saw a black name were less likely to answer them because of perceived poor socioeconomic status. In other words, that these public servants had not discriminated against the name because it were black-sounding, but because they assumed black people are more likely to be poor — a shining difference of course.

They did so by crafting the email to include the sender’s lucrative-enough profession, that of a real estate agent. But again, black names came up short.

“We find the racial gap to be 3.6 percentage points, namely almost identical to what we estimated in the first wave where there was no occupation signal,” they wrote. “This provides evidence that the differential response to white versus black names is not specific to black names that are associated with low socioeconomic background, but is also present when we compare emails sent by individuals who belong to a middle income occupational group.”

Additionally, when they were able to determine the racial identity of the email recipient, they noticed a smaller race gap when a black-named email was sent to a black-named recipient. There’s also the possibility that this effect could be worse the blacker-sounding the sender seems. While "DeShawn Jackson" and "Tyrone Washington" are distinctly black names, Jackson is a last name that many white people have whereas Washington is almost uniformly held by black individuals. And sure enough, the latter name received less replies back than the former.

Though these overall numbers could be considered small, they add to a larger picture of research showing similar discrimination in the job and housing markets, among many other fields of life. And they could point to an overall prejudice seen in public service sectors — after all, if a black parent’s email to their local school district gets ignored, the rest of their attempted interactions with school staff may not turn out any better.

“Besides being illegal, discrimination by public service providers is particularly startling, since governments could be major players in the effort to eradicate discrimination in American society,” the authors wrote. “For instance, school districts and libraries can play an important role in closing the educational achievement gap of black children.”

Unfortunately, there’s no simple solution to be found by the authors, though they do offer some prudent recommendations.

“The persistence of such practices despite their illegality suggests that they will not be eradicated through a quick legislative fix,” they concluded. “Possible interventions include hiring policies aimed at increasing diversity among the workforce or promoting racial matching between employees and the communities they serve.”

Source: Giulietti C, Tonin M, Vlassopoulos, M. Racial Discrimination in Local Public Services: A Field Experiment in the US. Institute for the Study of Labor. 2015.