Mapping Spread of Alzheimer's Disease Gives Clues to Stopping Progression

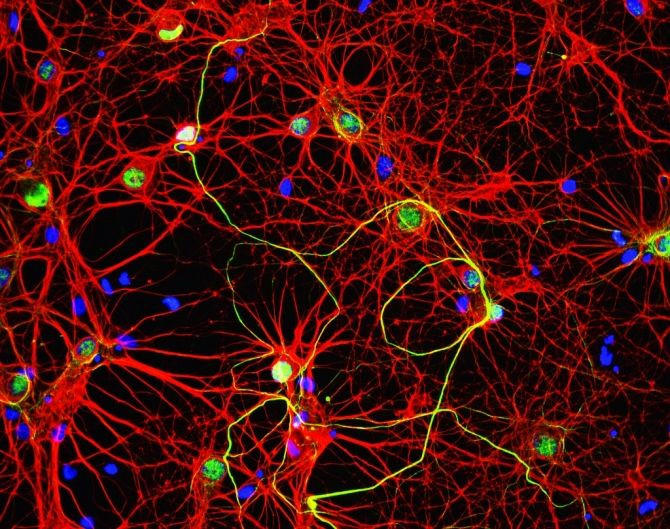

New research shows that Alzheimer’s disease may spread throughout brain regions by way of circuits known as synapses that link one brain cell to another.

The new study, published on Wednesday in the online journal PloS One, raises hope that researchers may soon be able to stop Alzheimer's disease and other neurological diseases from progression.

Alzheimer's disease, the most common form of dementia, has no cure and it worsens at it progresses, eventually leading to death. The illness is characterized by the build-up of amyloid-beta protein plaques and fibrous tangles composed of abnormal tau proteins in neurons called brain cells.

Tau is present in normal brains, and exists in individual units that are essential to neuron health. However in the cells of brains affected by Alzheimer’s, tau proteins bunch into twisted structures called neurofibrillary tangles that are considered a hallmark of the disease.

Researchers from Columbia University Medical Center used mice that were genetically engineered to accumulate deposits of tau in the entorhinal cortex, an important memory center of the brain where abnormal tau protein starts to deposit in people.

Researchers mapped the progression of abnormal tau in the brains of people affected with the mental illness by periodically analyzing the brains of the experimental mice over a period of 22 months.

The results showed that as the mice aged, the abnormal tau protein spread along a linked pathway, spreading from the entorhinal cortex to the hippocampus to the neocortex, parts of the brain that are essential to form and store memories. While the experiments were done on mice, researchers said that the pattern is very similar to the progression of Alzheimer’s in people.

Researchers also observed signs that tau travelled from brain cell to brain cell across synapses, linking points that allow one nerve cell to communicate with another.

These findings may lead to new methods for diagnosing and treating Alzheimer’s disease. The most effective approach to treat the illness may be the way cancer is currently treated, through early detection and treatment, before it has a chance to spread, according to co-author Dr. Scott Small, professor of the Taub Institute for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and the Aging Brain at CUMC.

"First, it would suggest that imaging tools that can detect entorhinal cortex dysfunction will be particularly helpful in diagnosing the earliest stages of the disease," researchers said in a statement.

"The implication of our study is that if it were possible to 'treat' Alzheimer's when it was first detected in the entorhinal cortex, this would prevent spread," they explained.

Senior author Dr. Karen Duff, professor of pathology at CUMC said that treatments for the brain disease could also target tau during the extracellular phase, as it moves from cell to cell.

"If we can find the mechanism by which tau spreads from one cell to another, we could potentially stop it from jumping across the synapses — perhaps using some type of immunotherapy. This would prevent the disease from spreading to other regions of the brain, which is associated with more severe dementia," Duff explained.

Previous imaging studies have also supported the pattern of spread that was documented in the new research. However, those findings failed to “definitively show” that Alzheimer’s spreads directly from one brain region to another, Small said.

"In the past, we have asked many of our colleagues in the field of Alzheimer's research what they mean when they say 'spread'. Most think that the disease just pops up in different areas of the brain over time, not that the disease actively jumps from one area to the next," researchers said.

"Our findings show for the first time that the latter might be true," they concluded.

Published by Medicaldaily.com