Medical Marijuana Isn't As Well Understood As It Could Be, Thanks To Federal Restrictions On Research

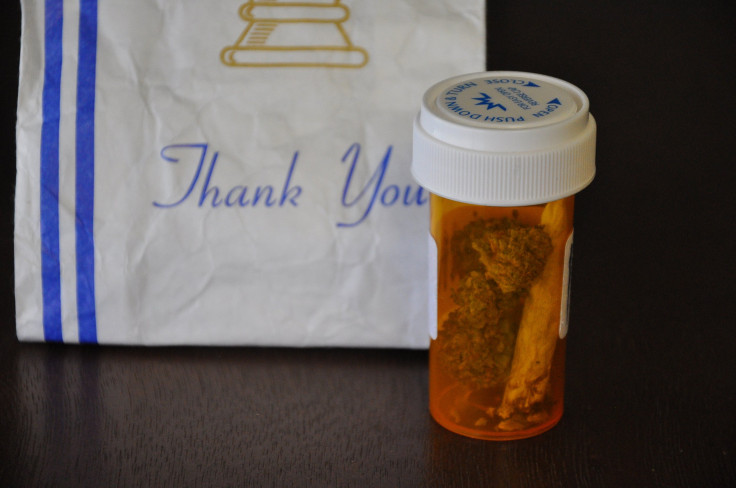

Marijuana use is no longer the taboo it once was. It’d be hard to justify even calling it a taboo, considering it’s a big topic of debate among presidential candidates, and it’s been legalized for both medical and recreational use in several states. Still, though, government policies that have remained largely unchanged for decades are inhibiting researchers from fully exploring marijuana’s medical benefits.

Tuesday’s Brooking’s Institution report took on the challenge of navigating the numerous legal and regulatory barriers to de-stigmatizing marijuana research, explaining how the U.S. government has held back scientific research that the medical community needs. The report argues that since states and the public are growing more open to the idea of medical marijuana and legalization, the federal government should keep pace.

A Scientific Issue, Not A Marijuana Issue

Currently, many patients and doctors are using a “learn-as-you-go approach” to medical marijuana, a situation that would be considered unreasonable for any other substance.

“This same conversation would be had if such barriers hindered the study of morphine or diazepam or Propofol or any other drug,” the report, written by John Hudak and Grace Wallack, states. Yet, of all the controlled substances that the federal government regulates, cannabis is treated in a unique manner in ways that specifically impede research.

The problem, one of the authors says, is about scientific freedom rather than laxness about marijuana, which stems mainly from marijuana’s classification as a Schedule I drug by the Drug Enforcement Administration — the most strictly regulated group of drugs, and one that assigns a tag of “no medical value” to its inhabitants.

This is a bit of a conundrum, since it is the strict regulations on marijuana research that have kept scientists from cementing the substance’s place in medicine. Though it is possible to obtain the necessary licenses and go-aheads necessary to legally research cannabis, the hassle of the process and the stigma surrounding the plant are enough to drive many researchers away. Both of these issues, according to the report, could be addressed by rescheduling marijuana to Schedule II.

“Federal recognition of an accepted medical use for marijuana would be an important signal to the medical and policy communities that this avenue of research is supported — or at least that it is not something the government is actively skeptical of,” the report reads.

For those imagining a floodgate of marijuana acceptance in popular culture, it’s OK to relax — reclassifying the substance would put it in the same category as cocaine, methamphetamine, and oxycodone, drugs considered dangerous and taboo by most people. It’s also important to note that states still have a say in the matter.

“If the federal government rescheduled marijuana, many states would follow suit, but states could also choose to impose more stringent restrictions on researchers using marijuana for medical research,” the researchers write.

Even when — and a big if — marijuana is rescheduled, a plethora of barriers remain for researchers. Restrictions on the number of growing operations allowed for government-approved research efforts is one example, one of the things researchers suggest several executive actions could remedy.

Freedom for scientists to study marijuana more freely would not only benefit those who are open to medical marijuana, but those who are skeptical as well — more research can only mean more certainty when it comes to the effects of cannabis.

Published by Medicaldaily.com