Men's Y Sex Chromosome Is Here To Stay Despite Being 'Puny'; Evolution Will Prevent Male Fertility Genes From Demise, Study Says

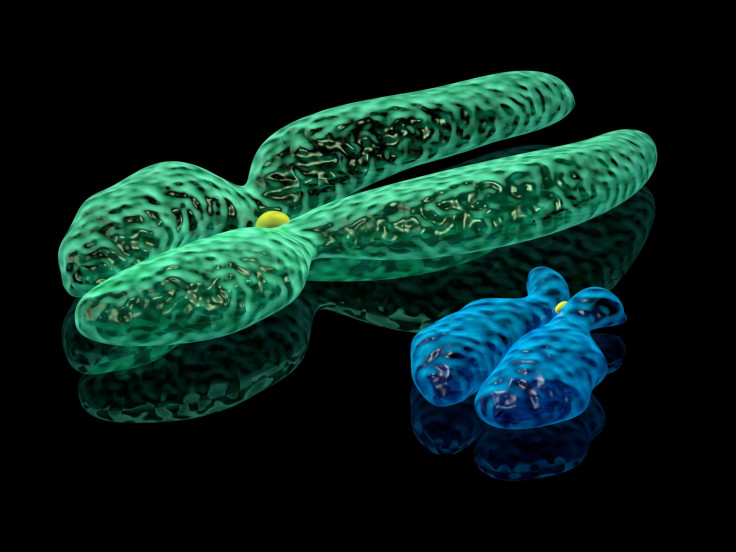

When compared with the X sex chromosome, some view the uniquely male Y sex chromosome as a shadow of its former self that will eventually diminish and disappear. But the findings in a study in PLoS Genetics conclude otherwise, challenging the notion that the genes contained on this relatively small strip of DNA are unimportant and disposable.

"The Y chromosome has lost 90 percent of the genes it once shared with the X chromosome, and some scientists have speculated that the Y chromosome will disappear in less than 5 million years," observed lead author of the study and evolutionary biologist, Melissa Wilson Sayres, who is part of the Department of Integrative Biology at the University of California, Berkeley. "Our study demonstrates that the genes that have been maintained, and those that migrated from the X to the Y, are important, and the human Y is going to stick around for a long while," she explained in a press release.

Decline In Genetic Stature

The Y chromosome is one of two sex chromosomes that humans and almost all mammals have. It is equipped with the genes that are responsible for the development of testis, and thus carried the blueprint for maleness. The idea that this chromosome is practically superfluous — or is at least approaching a state of redundancy — partly stems from the fact that it doesn’t recombine its genetic information with another chromosome to maintain an optimal genetic tool kit like the other 22 chromosomes do. It is also suspected that the Y chromosome’s modest 27 unique genes compared with thousands contained on other chromosomes has to do with the mating record of males not being as successful as females’ throughout history, which means fewer types of Y chromosomes have been passed on to subsequent generations.

This has led to the view that the Y chromosome has become a genetic “wasteland” that’s waiting to be put out of its misery in a matter of geological seconds. Yet experts like Dr. Jennifer Hughes, a research scientist at the Whitehead Institute, has pointed out the increasing appreciation for the Y chromosome’s biological functions and medical relevance, especially with regard to male fertility.

Chromosomal Redemption

In the current study, Wilson Sayres and other Berkley colleagues compared the Y chromosome of eight African and eight European men and found patterns of variation indicating that rather than diminishing into obscurity, natural selection is actually maintaining its genetic content because it plays such an important role in male fertility. "Melissa's results are quite stunning,” observed Berkley colleague and study co-author, Rasmus Nielsen, in the release. “They show that because there is so much natural selection working on the Y chromosome, there has to be a lot more function on the chromosome than people previously thought."

This lack of genetic variation of the Y chromosome is observed across the entire world and is actually what makes this sex chromosome so interesting and informative; by hardly changing over millions of years, it becomes a unique genetic time capsule that can be used to chart the course of human history, the authors explain. Furthermore, the Berkley researchers showed that the Y chromosome’s limited variation and small size doesn’t entirely have to do with fewer males successfully passing on their genes to the next generation. They calculated that such a scenario would require less than a fourth of males to have passed on their Y chromosome to the next generation throughout history, which they view as highly unlikely. Instead, they figured that evolutionary pressure was also involved with cutting the chromosome down to size. “We show that a model of purifying selection acting on the Y chromosome to remove harmful mutations, in combination with a moderate reduction in the number of males that are passing on their Y chromosomes, can explain low Y diversity," Wilson Sayres said.

Of the 27 genes that are on the Y chromosome, Wilson Sayres’ team found that 17 of them have been around for over 200 million years while the rest were acquired more recently. Male infertility has been linked to one or more copies of these newer genes getting lost along the reproductive way.

Source: Wilson Sayres M, Lohmueller K, Nielsen R. Natural Selection Reduced Diversity on Human Y Chromosomes. PLoS Genetics. 2014.