MS Symptoms May Be Predicted By Antibody Detected In Your Blood Years Before Warning Signs Appear

Worldwide, more than 2.3 million people are affected by multiple sclerosis (MS), a chronic, unpredictable disease of the central nervous system. A new study supported by the German Ministry for Education and Research has discovered a particular antibody that is found in the blood of people with MS may be present long before the onset of the disease and its symptoms. "Finding the disease before symptoms appear means we can better prepare to treat and possibly even prevent those symptoms,” study author Dr. Viola Biberacher, Technical University in Munich, Germany, stated in a press release.

What Are MS Symptoms?

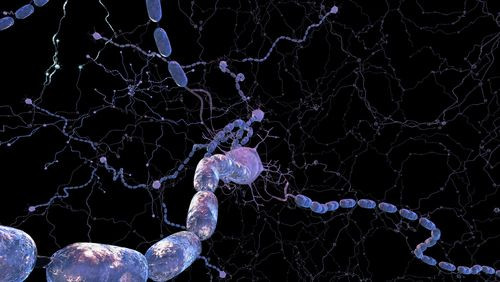

Most people are diagnosed with MS between the ages of 20 and 50, but children as young as 2 and adults as old as 75 have developed the disease. MS is thought by some to be an autoimmune disorder that particularly damages myelin, the protective insulation surrounding nerve fibers of the central nervous system (the brain, optic nerves, and spinal cord). Ravaged myelin, which is often compared to insulating material around an electrical wire, is replaced by scars of hardened “sclerotic” tissue which interferes with the transmission of nerve signals. Most people diagnosed with MS live a normal or near-normal lifespan though severe cases can shorten someone’s life. Symptoms are unpredictable and vary from person to person. One person, for example, may experience abnormal fatigue and episodes of numbness and tingling, while someone else suffers a loss of balance and muscle coordination and yet another has slurred speech, tremors, stiffness, and bladder problems. Major symptoms sometimes disappear completely. In severe MS, though, symptoms become permanent and include partial or complete paralysis, and difficulties with vision, cognition, speech, and elimination.

For the German study, 16 blood donors who were later diagnosed with MS were compared to 16 blood donors of the same age and sex who did not develop MS. Samples had been collected between two and nine months before the first symptoms of MS appeared and scientists looked for a specific antibody — a protein produced by the body's immune system when it detects harmful substances known as antigens — to KIR4.1. All of the healthy controls tested negative for the KIR4.1 antibody. Of those who later developed MS, seven people tested positive for the antibodies, two showed borderline activity and seven were negative. Next, researchers looked at antibody levels in the blood at additional time points up to six years before and then after disease onset in those who had the KIR4.1 antibody in their blood. The researchers found KIR4.1 antibodies several years before the first attack of MS, though concentrations varied for individual people at different time points.

"The next step is to confirm these findings in larger groups and determine how many years before onset of disease the antibody response develops," Biberacher said. Her research, conducted with colleagues, will be presented at the American Academy of Neurology's 66th Annual Meeting in April.

Published by Medicaldaily.com