Nanotechnology Sees Upgrade With Accelerated NanoMRI Process; Commercial Use Moves Closer

How do you view nanoscale materials, such as viruses and cells, up close and in-depth? You use a nanoMRI, of course. Now researchers from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich have accelerated the nanoMRI measurement process, bringing the technology one step closer to widespread commercial use.

Producing images of nano-sized objects with near-atomic resolution is hugely difficult. More importantly, the process takes time. A single nanoMRI scan requires not hours, not days, but weeks to complete.

In general, magnetic resonance imaging works by exploiting the fact that certain atoms have nuclei that act like tiny spinning magnets. If you bring these atoms into a magnetic field, they will rotate around the field’s axis the same way a spinning top rotates when it is imperfectly balanced and on a slant. This rotation is called precession and it happens at a precise frequency known as the Larmor frequency.

The Larmor frequency depends on both the type of atom and the general strength of the magnetic field. So to compose an image, an MRI essentially evaluates atoms’ locations by the frequencies at which they precess.

“When you look at a clinical MRI picture, you see bright pixels where the density of atoms is high, and dark pixels where the density is low,” Dr. Alexander Eichler, a postdoc researcher within the department of physics at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, stated in a press release.

When it comes to nanoMRI, though, the magnetic strength of nanomaterials is exceedingly small and so the sensitivity required of the technology is “at least a quadrillion times better,” Eichler explained. This has made it necessary to measure nano-sized information sequentially — one bit after another, a time-consuming process.

But what if you could measure the necessary information at the same time?

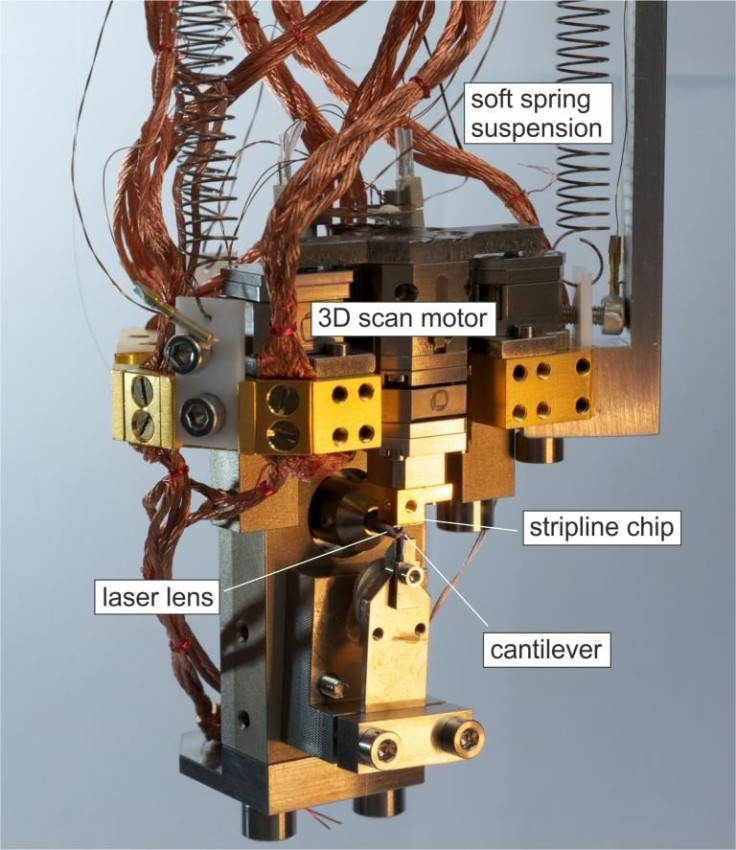

Such parallel measurement or multiplexing would require being able to distinguish where each bit of magnetic field information belongs in the final picture. While different strategies have been proposed, the research team in Zurich has developed a technique using a magnetic resonance force microscopy (MRFM) apparatus.

Here, the atomic nuclei experience a tiny magnetic force that is transferred to a cantilever, which acts as a mechanical detector. In response to the force, the cantilever vibrates and then, in turn, an image can be assembled from the measured vibration.

Using the new technique, a scan that normally might take two weeks can now occur within two days. Having overcome this major obstacle of high-resolution nanoMRI, the new research “brings us closer to the commercial implementation of nanoMRI,” Eichler concluded. In turn, this technology will allow scientists a closer view of cells and viruses, helping them advance their work on new medicines and vaccines.

Source: Moores BA, Eichler A, Tao Y, et al. Accelerated nanoscale magnetic resonance imaging through phase multiplexing. Applied Physics Letters. 2015.

Published by Medicaldaily.com