New Research Finds Low Risk Of Zika Virus At Olympics

CHICAGO (Reuters) - New research attempting to calculate the risk of the Zika virus at the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro may reassure organizers and many of the more than 500,000 athletes and fans expected to travel to the epicenter of the epidemic.

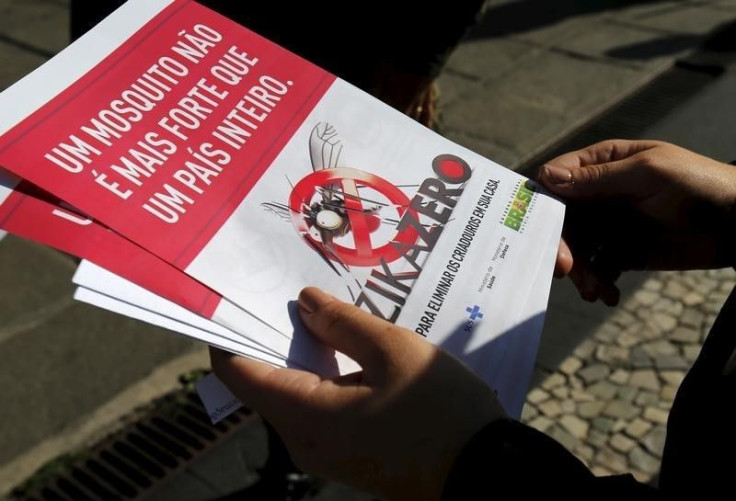

Controversy about the global gathering in August has grown as more about the disease becomes known. The mosquito-borne virus can cause crippling birth defects and, in adults, has been linked to the neurological disorder Guillain-Barre.

The World Health Organization, acknowledging the concern, has called a meeting of its Zika experts to evaluate the transmission risk posed by the Olympics.

The debate has played out largely in the absence of models calculating the risk to tourists attending the Olympics. New projections obtained by Reuters suggest the risk is small.

One Sao Paulo-based research group predicted the Rio Olympics would result in no more than 15 Zika infections among the foreign visitors expected to attend the event, according to data reviewed by Reuters.

The projection echoes that of a separate group of Brazilian scientists, also based at the University of Sao Paulo, in a study published in the journal Epidemiology & Infection in April. It found the Olympics would result in no more than 16 additional cases of the disease.

Neither study attempted to assess the risk of even a single Olympics traveler carrying the virus back to a vulnerable home country - a central concern of recent calls to reconsider the venue of the Games.

But a team of U.S. government epidemiologists calculated that Olympics visitors would account for .25 percent of the total risk of spreading Zika through air travel. That was based on 2015 data showing about 240 million people moved to and from areas that now have active transmission.

"Even if the Games were totally shut off and stopped, and the whole thing were canceled, 99 percent of that risk is still ongoing," Dr. Martin Cetron, director of global migration and quarantine for the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview.

Questions about whether the Games should go on arose in February when WHO declared Zika a global health emergency based on reports of a spike in a typically rare birth defect in Brazil. Since then, Brazil has identified more than 1,400 cases of microcephaly, a condition defined by small head size and underdeveloped brains, linked to Zika.

The WHO and CDC warned pregnant women against traveling to Zika outbreak areas, and advised men exposed to or infected with the virus to practice safe sex, or abstain altogether, for weeks to months upon their return.

Several would-be Olympians have voiced concerns about competing in Rio.

In the most direct critique to date, more than 200 bioethicists, lawyers and health experts sent a letter to WHO Director-General Margaret Chan calling for the Games to be moved or postponed. WHO rejected the idea, saying it lacked scientific merit. Notably, WHO officials said, August is a low season for mosquitoes in Rio and the virus has already spread well beyond Brazil.

But late last week, WHO said its Emergency Committee on Zika would meet this month to assess what is known about the risk. The agency said it was up to the International Olympic Committee to make any decision about changing the Games.

NEW RISK ASSESSMENTS

One new risk analysis assumed that if 500,000 people attend the Olympics, the Games would add five to 15 Zika cases to what would otherwise occur.

The projection was developed by a team of researchers at the University of Sao Paulo and submitted to The Lancet early last week. As of last Thursday, the British medical journal had yet to accept it for publication. But Dr. Eduardo Massad, the medical informatics professor who led the effort, shared a copy with Reuters.

"If you are not pregnant and decided not to attend the Rio Olympics this year out of fear of Zika infection, you'd rather find a better reason; there are many others," Massad wrote in his letter to The Lancet, citing higher rates of crime and dengue.

Previously in The Lancet's Infectious Diseases journal, Massad’s group pegged the risk of dengue among the expected 600,000 visitors to the 2014 World Cup in Brazil at three to 59 cases. The forecast was lower than others but was ultimately borne out: Three cases of dengue were confirmed during the global soccer championship.

Another group of scientists from Brazil's Oswaldo Cruz Foundation recently estimated infections of dengue - which they view as a proxy for the spread of Zika - could range up to 36 cases among Olympic tourists, according to an opinion piece published June 2 in Memorias Do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, a peer-reviewed medical journal.

The estimate was based on historical patterns of dengue infection in Rio in August and assumed tourists have the same risk exposure as residents. The risk of Zika infection, which is transmitted by the same mosquito, would likely be even lower, said to Marcelo Gomes, an expert in computational physics at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation and one of the study's authors.

Olympics visitors are more likely to stay in areas with greater protection against mosquitoes, including window screens and insecticide, he said in an email, while Aedes aegypti mosquitoes also are less efficient at carrying Zika than dengue.

The research teams, as well as other disease experts, seek to refute concerns raised in the public letter to WHO. In it, Amir Attaran, a professor of law and medicine at the University of Ottawa, and colleagues wrote that the influx of visitors to Brazil would result in otherwise avoidable birth defects.

Attaran told Reuters he does not trust the estimate of Massad and his colleagues because the virus is so new to Brazil that their underlying assumptions could be wrong.

Gomes countered that there was evidence to show Zika infection patterns were similar enough to the long-studied dengue virus to create a reliable risk model.

Research provided to Reuters by WHO also suggested the risk of contracting Zika while at the Olympics was low and the benefit from canceling the games was small.

Alessandro Vespignani - a professor of physics, computer science and health sciences at Northeastern University in Boston - is developing a model that predicts where the virus will spread based on travel patterns to and from places where the virus already is being transmitted.

The model is based on the CDC’s list of more than 30 Latin American and Caribbean countries where Zika is present.

Based on his work, he said, the contribution of the Olympics to the global spread of Zika “is a fraction of a percent. This is a number that at this point doesn't really make a difference.”

Attaran said such calculations fail to consider the special nature of the Olympics, which draws travelers from places with high concentrations of Aedes species mosquitoes capable of carrying the virus. He also noted that slum-like conditions in Brazil help fuel the spread of Zika there.

He pointed to an analysis by Nuno Faria of Oxford University that suggested Zika was carried to Brazil by a single individual in late 2013. By early 2016, as many as 1.5 million people in the country were estimated to have been infected.

"People can legitimately argue about the magnitude of the risk," Attaran said. "Nobody is denying the risk exists."

(Reporting by Julie Steenhuysen; Editing by Michele Gershberg and Lisa Girion)