New Tumor Shrinking Antibody Treatment Has Cure Potential for 7 Cancers

A drug being developed to help the immune system break down cancerous tumors has been found to shrink breast, bowel, prostate, ovarian, brain, bladder, liver and some blood cancers that have been transplanted into mice, according to a new study.

The latest research suggests that the drug may even be a cure if given early, and while the drug has only been tested on mice, researchers hope to start giving it to people within two years.

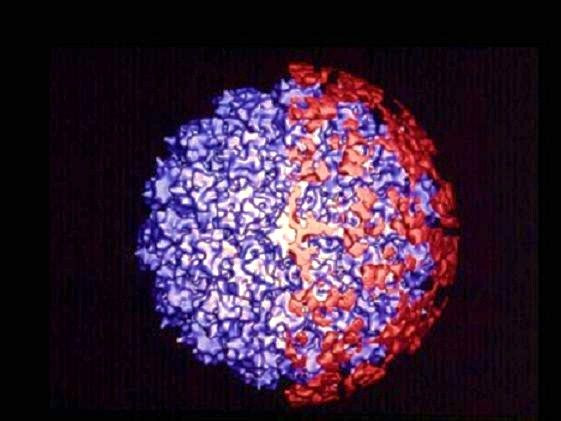

The antibody treatment is a protein used by the immune system to destroy foreign cells and works by blocking a CD47 “do not eat” signal, normally found on cancer cells to save them from being destroyed by antibodies. Scientists from the study said that the treatment appeared to be safe and effective after testing it in mice.

"Blocking this 'don't-eat-me' signal inhibits the growth in mice of nearly every human cancer we tested, with minimal toxicity," Dr. Irving Weissman, professor of pathology who directs Stanford's Institute of Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, said in a university statement released on Monday. "This shows conclusively that this protein, CD47, is a legitimate and promising target for human cancer therapy."

Previously Weissman and his research team found that leukemia cells produce higher levels of CD47 protein than healthy cells that also display the protein. Researchers explain that the protein is a marker that blocks the immune system from killing them as they circulate, and cancer cells take advantage of the protein signal to trick the immune system into ignoring them.

They found that blocking the CD47 protein stimulated the immune system to recognize the cancer cells as invaders, and thus cured some cases of lymphoma and leukemia in mice.

Researchers said that the findings show that the anti-CD47 antibodies significantly inhibited the growth of human cancer tumors, and noted that while tumors did not shrink in some mice, the drug stopped the cancer from spreading to other parts of the body.

"If the tumor was highly aggressive, the antibody also blocked metastasis," Weissman said. "It's becoming very clear that, in order for a cancer to survive in the body, it has to find some way to evade the cells of the innate immune system."

Weissman also noted that the treatment failed to work for some mice with breast cancer cells from a particular human patient.

Researchers are also unsure if reducing the tumor size with radiation or surgery before the antibody treatment would be more beneficial, and they suggest that by using a second antibody in addition to CD47 may further stimulate the ability of macrophages or other immune system cells to destroy cancer cells.

"There's certainly more to learn," said Weissman. "We need to learn more about the relationship between macrophages and tumor cells, and how to draw more macrophages to the tumors."

Cancer researcher Tyler Jacks of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge told Science that while the new findings in mice are promising, more research needs to be done to seen whether the results would also hold true in people.

"The microenvironment of a real tumor is quite a bit more complicated than the microenvironment of a transplanted tumor," Jacks said, "and it's possible that a real tumor has additional immune suppressing effects."

The findings were published in the March 26 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.