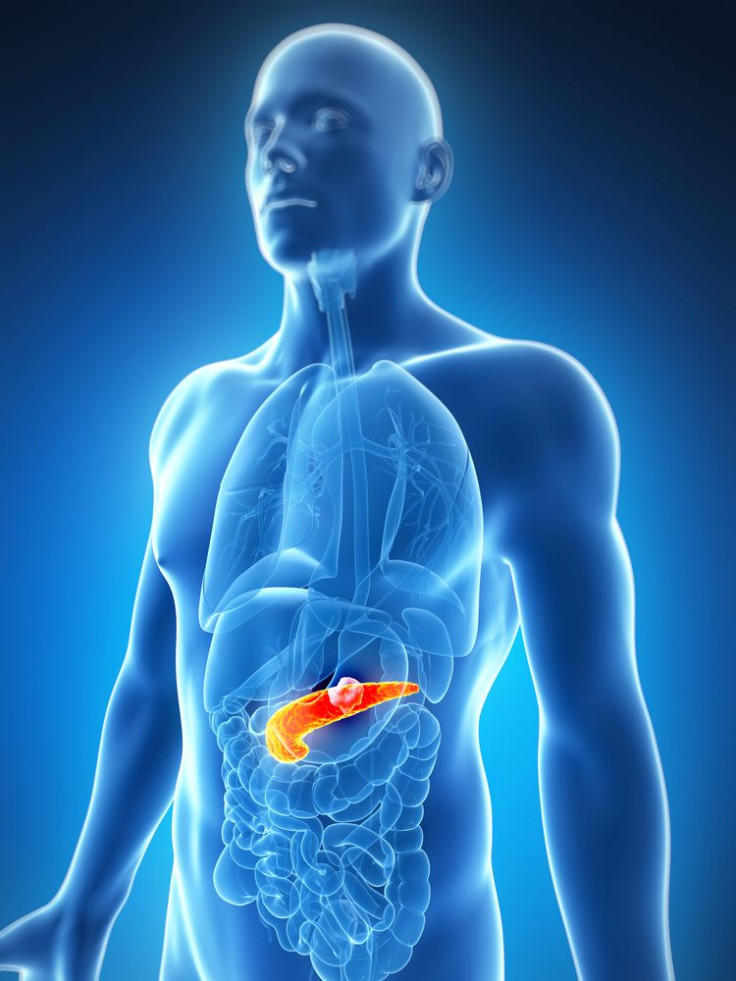

New Vaccine ‘Reprograms’ Pancreatic Tumor To Make It More Responsive To Immunotherapy

Pancreatic cancer is lethal due to its resistance to conventional chemotherapy and other treatment approaches. But a new vaccine developed at Johns Hopkins' Kimmel Cancer Center re-programs the microenvironment of the tumor, making it more vulnerable to the body’s immune responses and thus also to immune-based therapies.

The study was published in Cancer Immunology Research, June 18. The team tested the vaccine in 39 people with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC), which accounts for more than 90 percent of pancreatic cancer cases. Diagnosis is difficult, as the symptoms are vague and more often than not the cancer is caught in the later stages, which is why it does not respond well to treatments. It is estimated that close to 44,000 Americans will be diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and more than 37,000 will die.

PDACs do not generally trigger immune responses but the new vaccine developed by Johns Hopkins researcher Elizabeth Jaffee, M.D., "reprogramed" tumors to include cancer-fighting immune system T cells, according to a press report. The vaccine, known as GVAX, consists of irradiated tumor cells that have been modified to trigger immune responses against the tumor. The researchers tested GVAX in combination with an immune modulator drug called cyclophosphamide that can supress regulatory T cells (Tregs) that prevent antitumor immune responses of certain T cells.When modified, the tumor will become more susceptible to immune-modulating drugs that have been useful in fighting other cancers, said Jaffee, The Dana and Albert "Cubby" Broccoli Professor of Oncology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

The vaccine modifies different types of tumors so that they become more responsive to immunotherapies. For example, Jaffee says, in certain melanomas, "we've tested immunotherapies that target T cells and have found a 10-30 percent response in cancers that naturally have the ability to trigger immune system responses, but there are few options for the other 70 percent of patients who barely or never respond to immunotherapies."

According to the researchers, the vaccine worked by creating structures called tertiary lymphoid aggregates within the patients' tumor. These structures display characteristics similar to organs like lymph nodes and regulate immune cell activation and movement. The aggregates, which appeared in 33 of the 39 patients treated with the vaccine, exhibited well-organized structures that do not typically appear in these types of tumors naturally, said coresearcher Lei Zheng. "This suggests that there has been significant reprogramming of lymphocyte structures within the tumor."

The aggregates could "really shift the immunologic balance within a tumor, setting up an environment to activate good T cells to fight the cancer, by tamping down Tregs," Jaffee said, "and such T cells would be educated to recognize the cancer proteins in that specific tumor environment." The vaccine and the resulting lymphoid aggregates boosted the activity of several molecular pathways that supress cancer-fighting immune cells and provide potential targets within the tumor for immune-modulating drugs.

The researchers next plan to test the effectiveness of a combination of GVAX and an antibody to PD-1, one of the immune-suppressing molecules that became more active after vaccination.

"We think combinations of immune therapies will have the biggest impact," said Zheng.