Opioid Painkillers: Why Some States Prescribe More And Kill More People From Overdoses

We’ve heard a lot about the increase of opioid painkiller prescriptions — and fatal overdoses — in recent months. At this point, plenty of health care providers have warned that the “treatment is the problem,” as nearly three out of four prescription drug overdoses are caused by painkillers.

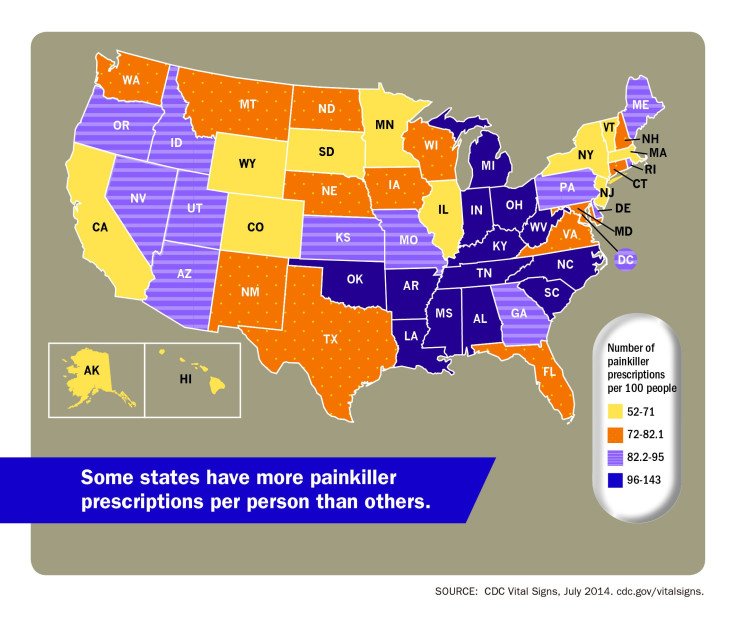

According to a new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report, Vital Signs, the amount of painkillers prescribed to patients varies significantly across states — with some prescribing three times as many as others. A swath of Southern states, in particular, are the worst offenders: Alabama, West Virginia, Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Kentucky prescribe nearly three times as many painkillers as some of the lowest states of New Jersey, New York, Minnesota, California, and Hawaii. For example, 22 times as many prescriptions were written for oxymorphone — a type of painkiller that treats moderate to severe pain — in Tennessee as in Minnesota.

“Prescription drug overdose is epidemic in the United States,” CDC Director Tom Frieden said in a press release. “All too often, and in far too many communities, the treatment is becoming the problem. Overdose rates are higher where these drugs are prescribed more frequently. States and practices where prescribing rates are highest need to take a particularly hard look at ways to reduce the inappropriate prescription of these dangerous drugs.”

Indeed, the epidemic has grown threefold since 1990, with triple the amount of deaths from prescription painkillers occurring now than they did before. In 2012, health care providers wrote 259 million prescriptions for opioid painkillers, according to the Vital Signs report. And the number of overdose deaths from painkillers is twice as many as those from heroin and cocaine combined. Sometimes, people who end up addicted to heroin started out on painkillers: “In some ways, it’s a single epidemic,” Frieden said.

According to the CDC, for every painkiller-related death, there are 10 treatment admissions for abuse, 32 emergency department visits for misuse or abuse, 130 people who are addicted, and 825 non-medical users.

But the situation isn’t black and white. Perhaps what makes the opioid painkiller debate so frustrating is the fact that many chronic pain sufferers truly rely on these medications in order to function daily. And a good number of painkiller abusers and opioid addicts actually started out as street drug users, not pain patients. These people get the pain medication from a friend or relative, through dealers, theft, or prescription forgery, so it’s difficult to figure out where to lay the blame. “Almost all prescription drugs involved in overdoses come from prescriptions originally; very few come from pharmacy theft,” the CDC states. “However, once they are prescribed and dispensed, prescription drugs are frequently diverted to people using them without prescriptions.”

The CDC and health care providers hope to tackle the epidemic by implementing prescription drug monitoring programs, which can help identify over-prescription problems, and considering policy options like laws and regulation to better handle prescription practices. In addition, the CDC suggests increasing access to substance abuse treatment facilities to be better prepared when people overdose on painkillers. “We know we can do better,” Dr. Daniel M. Sosin, acting director of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, said in the press release. “Improving how opioids are prescribed will help us prevent the 46 prescription painkiller overdose deaths that occur each day in the United States.”