Proton Beam Therapy: Is It Really Necessary For Treating Cancer?

Proton beam therapy, which is twice the cost of conventional radiotherapy, is available in 11 medical centers throughout the U.S. and 17 more facilities are slated to be built. But with health care spending still out of control, some experts are debating whether they're necessary.

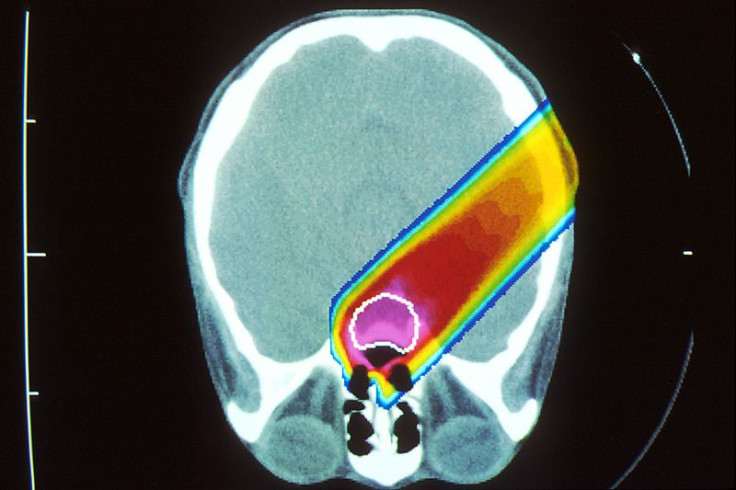

Proton therapy involves a cyclotron, which accelerates protons to two-thirds the speed of light. These protons are then directed toward the tumor where the radiation is released. The proton beam is so focused that only the tumor is affected by the radiation, sparing the surrounding tissues which would be radiated with conventional photon radiotherapy. Proponents of the therapy believe that this will lead to fewer side effects.

Proton therapy has shown promise for treating brain and spinal tumors on children, because the focused beam protects the developing cells surrounding the tumors from side effects. However, there is a lack of clinical evidence that supports that proton beam therapy is any better than standard photon radiation machines in other populations.

"We believe that this therapy is absolutely necessary, but we also think that it's appropriate to be applied to certain types of cancer with certain treatments and not everything," Chip Davis told Kaiser Health News. Davis is the president of Sibley Memorial Hospital, where the Hopkins proton center will be built.

Sibley Memorial Hospital is part of the Johns Hopkins hospital systems in Washington, D.C. and is one of two facilities in the area that was recently approved by the local government to build a proton center. The other facility is MedStar Health's Georgetown University Hospital. The total expected cost of both centers is $153 million. There is also a treatment center in the process of being built just 40 miles away in Baltimore.

Dr. Minesh Mehta, who will direct the Maryland Proton Treatment Center, understands that proton therapy is most beneficial to children, but he says that of the 200 patients they see a day, 90 percent will be adults, and 35 percent of those will have prostate cancer.

"It's hard to find a lot of children with brain cancers you can treat with the device, but you can find millions of men with prostate cancer," Amitabh Chandra, an economist and professor of public policy at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, said.

Mehta acknowledged that the proton therapy hasn't proved increased efficacy in any clinical trials outside of children with brain cancers. He argues that studies showing proton therapy isn't any better in treating prostate cancer were based on flawed data and didn't accurately portray the potential of proton therapy.

"At the end of the day, when I tell a patient I can treat you with the technology that will treat less of your normal tissue with radiation you don't need versus more radiation to tissue that should not be radiated, which would you like to choose?" Mehta said. "The vast majority of patients will choose the technology that gives less radiation to their tissues."

But while some experts are excited about the new technology, others don't see the point.

"Neither should be building," Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, a former health care adviser to the Obama Administration, said. "We don't have evidence that there's a need for them in terms of medical care. They're simply done to generate profits."

The machine at the Sibley Memorial Hospital is expected to generate $15.8 million by 2019, but at twice the price of standard photon therapy, the cost of the machines is expected to trickle down to taxpayers, employers, and consumers through higher health insurance premiums.

"It's hard to bend the cost curve when you're spending a lot of money," Emanuel said. "These are tens if not hundreds of thousands of dollars in treatment for interventions that do not improve survival, improve quality of life, decrease side effects, or save money."

Published by Medicaldaily.com