Color-Changing Wound Dressing May Someday Help Doctors Quickly Treat Infections — And Avoid Antibiotic Resistance

It’s a relatively simple invention that may someday help doctors better combat infections and forestall antibiotic resistance — and it’s pretty cool-looking to boot.

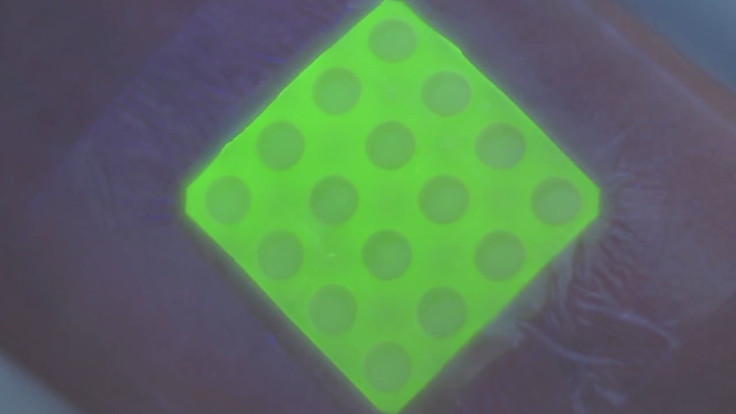

This November, University of Bath researchers in the UK announced that they are in the process of developing a new type of wound dressing capable of indicating whether a wound is actually infected by worrisome bacteria via a fluorescent color change.

“Our medical dressing works by releasing fluorescent dye from nanocapsules triggered by the toxins secreted by disease-causing bacteria within the wound,” explained lead researcher Dr. Toby Jenkins in a statement. “The nanocapsules mimic skin cells in that they only break open when toxic bacteria are present; they aren’t affected by the harmless bacteria that normally live on healthy skin.”

As Jenkins went on to note, that unintrusive warning sign could allow doctors to quickly identify infections without the waiting period of lengthy lab tests or having to replace the dressing for a physical examination. For the most severe wounds like burns, that patience may mean faster recovery time and less pain and scarring. “It could really help to save lives,” he said.

Almost as importantly, it will stop doctors from unnecessarily prescribing antibiotics to their patients as a precautionary measure. While antibiotics are no doubt an essential tool in medicine, their overuse has largely contributed to the growing ability for certain bacteria to resist conventional treatments.

“Children are at particular risk of serious infection from even a small burn. However, with current methods clinicians can’t tell whether a sick child might have a raised temperature due to a serious bacterial burn wound infection, or just from a simple cough or cold,” added Dr. Amber Young, Clinical Lead for the Healing Foundation Children’s Burns Research Centre at Bristol Children’s Hospital. “Being able to detect infection quickly and accurately with this wound dressing will make a real difference to the lives of thousands of young children by allowing doctors to provide the right care at the right time, and also, importantly, reduce the global threat of antibiotic resistance.”

Young, along with Jenkins and his colleagues, will coordinate efforts to test out the dressing in more real-world conditions, by subjecting it to samples derived from actual burn wound sufferers. The research is being supported by a nearly £1 million grant ($1.5 million US) from the Medical Research Council , “a national funding agency dedicated to improving human health by supporting research across the entire spectrum of medical sciences.”

Jenkins and his team are cautiously optimistic about their invention’s future. “Translating research from the laboratory towards the clinic is fraught with complexity, but this award will allow us to start this critical translational pathway,” he said. “Working with our industry partner, the funding will be used to design, manufacture and package a final prototype dressing, safe and ready for trial in humans.”

Should the dressing continue to meet expectations, it may see use in hospitals in about four years.