Real Brain Games: How Simple Playtime Affects Our Growth And Development

All humans and mammals take part in some form of play during their formative years, from dogs chasing one another, to rats wrestling, to toddlers playing with building blocks or little girls playing house. The act of play continues well into adulthood in the form of drinking games, parties, board games, and video games.

For a while, it was assumed that the act of play had a role in childhood development; playing house or creating adult-like scenarios with Barbie dolls helped children practice adulthood, in a way. Playing also gives kids a chance to practice social skills — learning that they have to share toys without throwing tantrums in order to keep playing. “In play, young mammals practice the very skills that they must develop in order to make it into adulthood,” Peter Gray, a professor of psychology at Boston College, told PBS. Play has been referred to plenty of times as a “dress rehearsal” of sorts for school and real life.

“Scientists who study play, in animals and humans alike, are developing a consensus view that play is something more than a way for restless kids to work off steam; more than a way for chubby kids to burn off calories; more than a frivolous luxury,” Robin Marantz Henig wrote in a 2008 New York Times article. “Play, in their view, is a central part of neurological growth and development — one important way that children build complex, skilled, responsive, socially adept and cognitively flexible brains.”

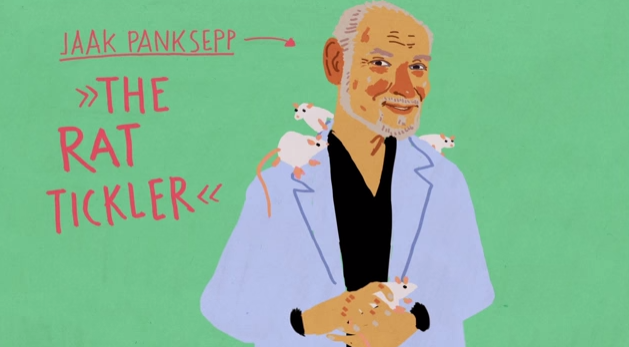

The video introduces Jaak Panksepp, a psychologist, psychobiologist, and neuroscientist who explains a fascinating theory about play. Panksepp sought to discover where exactly in the brain play originates — in the new part of the brain or the older, ancient part of the brain commonly associated with basic needs like food, sex, and sleep. In studying rats, Panksepp found that the play impulse indeed came from the primitive part of the brain. Because of this, he believes that play is vital for survival — because the act of playing hasn’t died off after years of natural selection. Play helps kids develop social skills and learn to navigate social situations and hierarchies. And it’s possible that play can lead to advantages later in life: in another one of Panskepp’s studies, he found that male rats that had played plentifully throughout their lives were more attractive to female rats.

“Play is a very valuable — not just superfluous — it’s a very valuable thing for child development, and we as a culture have to learn how to use it properly and have to make sure our kids get plenty of it,” Panksepp said in the video.