The Science Of Scars: Why Can't Our Skin Just Heal Itself Back To Normal?

For some cultures, scars are a symbol of beauty and group identity. But in the Western world, the best response they tend to get is one of nostalgia — memories of that slide you fell off when you were 5 or that dog that bit you on your way home from school. Ever wonder why you get them in the first place, though?

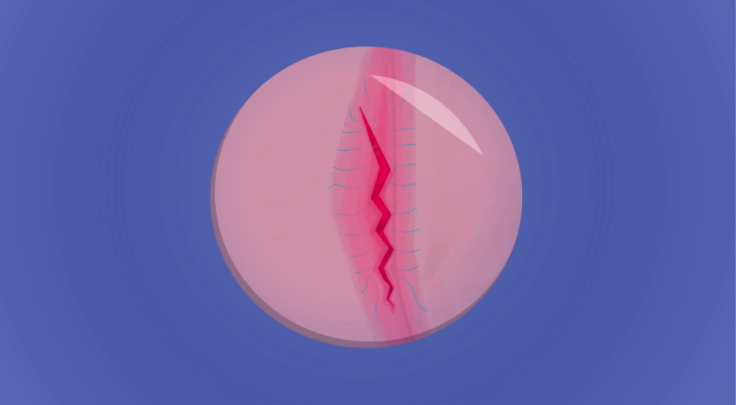

Healthy skin cells are connected by an extracellular matrix, or ECM. The ECM helps transport certain nutrients around the skin and keep the cells held together. It’s composed of certain proteins, such as collagen. When you fall off the slide or get bit by a dog, the wound disrupts the ECM’s neatly organized basket-weave structure. As the wound heals, the weave turns to straight lines and reduces elasticity and durability, not to mention slowing the processes inside the cell.

Scars are what the healed, yet disorganized, tissues look like. Though minor, the scars cause slight breakdowns in cell function, particularly if there is too much collagen or ECM. A surplus of collagen, for instance, hampers sweat production, deregulates body temperature, and can stimulate hair growth.

The best way to reduce long-term damage from scar tissue, then, is to protect it. That means bandages (or futuristic polymers). If too much fibrous tissue develops, experts refer to the condition as fibrosis, and it can happen in more organs than just the skin. Pulmonary fibrosis affects the lungs, and cystic fibrosis affects the pancreas. For visible scars, however, we can view them as reminders of the past — so we can appreciate the memories but still know not to do it again.