Rain Man’s Concussion: 4 Cases Of Acquired Savant Syndrome That Turned Regular Folks Into Geniuses

There are few people who are satisfied with their level of creativity. They could always be better artists, they think. Or better musicians. Or writers. Some dedicate their entire lives to molding this talent, while others merely gaze from the outside in. Then there are those people who, in a brilliant flash of accident and discovery, develop the abilities as the result of traumatic brain injury — people otherwise known as “acquired savants.”

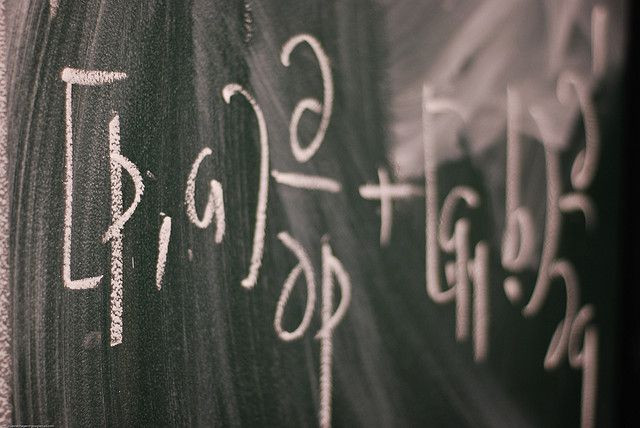

Science is a slippery mess when it comes to acquired savant syndrome. The closest scientists have come to understanding what happens in the brain when a concussion leads to mathematical or artistic genius is that more neural connections are being made. Psychologists generally regard creativity, in a basic sense, as the bridges your brain builds between unrelated parts. You see patterns where others don’t. Acquired savants stumble upon this dense web on accident, their talents mysteriously changed forever.

1. Derek Amato — The Pianist

Seven may be the magic number for Derek Amato, as it is the same number of concussions he’s sustained in his life and the number of hours he’d been playing the piano when the salesman at the music store inquired about his background.

The first concussion happened when Amato was in second grade, and he bashed into the monkey bars during a game of kickball. The seventh, and the one that forever made him a piano virtuoso, happened when dove headfirst into the shallow end of a swimming pool. He lost 35 percent of his hearing that day, and he still suffers brief headaches and light sensitivity, but he’s gained an ability that others train for years to achieve.

“I truly believe after meeting all these gifted people,” Amato said in a recent TED Talk, “that we all have this area somewhere inside our brain that will allow beautiful or genius or something new.”

2. Jason Padgett — The Geometer

Before he got mugged in Tacoma, Wisc., one night outside a karaoke bar, Jason Padgett was a college dropout with a young daughter and zero interest in academia. Immediately after a blow to the back of his head, Padgett fell unconscious. But when he woke up, the world was different.

“Suddenly, I’m able to basically process more information geometrically where before I couldn’t,” Padgett told Fox News. Soon after his injury, Padgett learned his newfound mathematical insights and drawing ability — he completes complex pencil drawings of fractals and other geometric shapes — were likely the result of acquired savant syndrome.

Now he meticulously produces these geometric drawings and teaches his daughter math. He admits, however, that his passion sometimes acts as handcuffs. “Yes,” he said, when asked if the ability impairs his daily life. “It does constantly.”

3. Ric Owens — The Artist

Before Feb. 9, 2011, Ric Owens was an executive chef working at Widener University. Following a run-in with a big rig on a Pennsylvania highway, Owens’ occasional migraines and slurred speech put him out of commission. He was forced to leave his job. But Owens didn’t become a recluse; his injury soon turned to artistic prowess.

"I see geometry now, I see the planes, the angles," he explained to The Philadelphia Inquirer at the time. "I never understood architecture before. Now, I stop and draw it." Owens completes intricate, detailed works of art, often on unexpected canvasses, and showcases them in galleries.

Owens calls himself the Accidental Artist. He no longer feels compelled to cook, as he had felt for the first 55 years of his life. Now, he dedicates his time to art. "I never know what's going to come out," he said of his artistic vision — or lack thereof. "I just let it happen."

4. Alonzo Clemons — The Sculptor

Alonzo Clemons was 3 years old when he suffered a severe fall. To this day, in his late fifties, Clemons still retains an IQ of no more than 50, and he can neither read nor write. His claim to fame, however, is his ability to sculpt. In a half hour, Clemons can shape a piece of clay into the shape of just about any animal. They range from mere inches high to full life-sized replicas, which have sold at exhibitions for upward of $45,000.

Clemons, like other savants, can’t describe why or how he came to acquire this ability. He simply saw the world one way before the accident, and another way after it. And given his young age at the time of his fall, researchers believe it’s unlikely something made its way in from the outside. It could be the case, according to Dr. Darold Treffert, the foremost expert on acquired savant syndrome, that the ability actually lies dormant inside everyone.

“These are people,” he explained, “who develop normally, are neurotypical, and have some kind of incident — it may be a stroke, it may be a head injury, it may be dementia — that unleashes some buried potential.”

Published by Medicaldaily.com