New Research Reveals Almost 400 Medical Reversals

The number of “medical reversals” is growing in number, illustrating a rising open-mindedness to new medical practices superior to their predecessors.

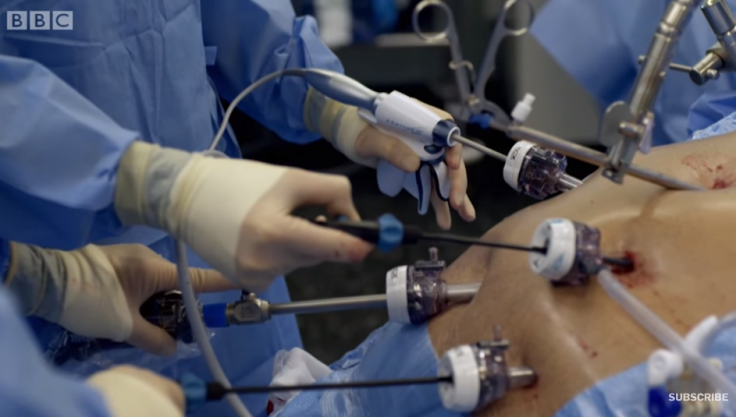

Medical reversals occur when new clinical research shows a certain medical practice doesn’t work, or does more harm than good. It often has to do with medications but can also affect surgical procedures

A new meta-analysis of 3,000 studies appearing in the journal eLife identified 396 cases of medical reversals. The new analysis to assess the validity of clinical practice was led by Dr. Diana Herrera-Perez, a research assistant at the Knight Cancer Institute at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) in Portland. She is also the lead author of the new analysis.

"We wanted to build on these and other efforts to provide a larger and more comprehensive list for clinicians and researchers to guide practice as they care for patients more effectively and economically,” said Herrera-Perez.

To do so, she and her colleagues examined over 3,000 randomized controlled trials published in three prestigious medical journals over the last 15 years: The Lancet, The Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) and The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

Their analysis discovered 396 medical reversals. Of this total, 154 were in JAMA, 129 in NEJM and 113 in The Lancet.

Researchers carried out 92 percent of the studies in high-income countries, while 8 percent were performed in low- or middle-income countries, including China, India, Malaysia, Ghana, Tanzania and Ethiopia.

Most of the medical reversals occurred in the fields of cardiovascular disease (20 percent), public health and preventive medicine (12 percent) and critical care (11 percent).

The most common interventions involved medications (33 percent), procedures (20 percent), vitamins and supplements (13 percent), devices (9 percent) and system interventions (8 percent).

There are a number of lessons that can be derived from the results. These include the importance of conducting randomized controlled trials for both novel and established practices, said Dr. Vinay Prasad, a hematologist-oncologist and associate professor at the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute.

He noted once an ineffective practice is established, it might be difficult to convince practitioners to abandon its use. Testing novel treatments rigorously before they become widespread can reduce the number of reversals in practice and prevent unnecessary harm to patients.

"We hope our broad results may serve as a starting point for researchers, policymakers, and payers who wish to have a list of practices that likely offer no net benefit to use in future work,” Prasad said.

Co-lead study author Dr. Alyson Haslam, Ph.D., who is also affiliated with the OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, said the team hopes its findings taken as a whole will help push medical professionals to evaluate their own practices critically and demand high-quality research before adopting a new practice in the future, “especially for those that are more expensive and/or aggressive than the current standard of care."