Revolutionary Treatment Uses HIV to Reprogram Cells Into Fighting Cancer

Emma Whitehead, now aged seven, was five years old when she was diagnosed with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Last spring, she was near death, having twice relapsed from chemotherapy. But this year, she has been in remission for seven months, has started the second grade, and has regained her childhood, according to her parents. She was able to do so with a revolutionary new treatment that appears to have allowed her own immune system to fight cancer.

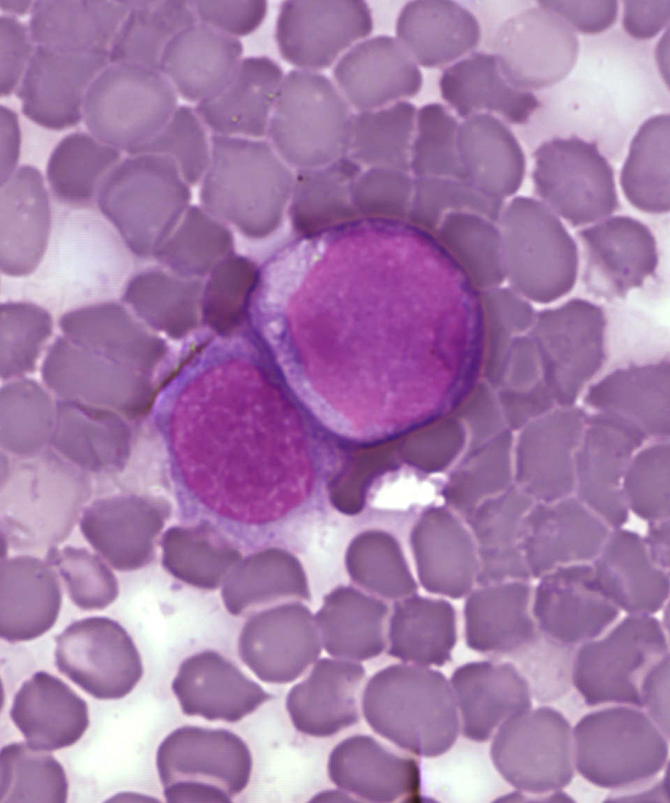

The treatment uses a disabled version of the virus that causes AIDS to reprogram the genes of a person's immune system and retrain it to kill cancer cells. Researchers remove millions of the patients' T-cells, a type of white blood cell, and insert new genes that would allow the T-cells to kill cancerous ones. Disabled HIV is used for the treatment because the virus is good at transmitting genetic material into T-cells. Then the engineered T-cells are pumped back into the body where they are intended to attack B-cells, which turn malignant during leukemia. The reengineered cells can stay in the body for years, though not at the same level as when fighting the disease.

Emma is just one of a dozen patients, and only a few children, who have had the treatment. It is imperfect - the treatment itself nearly killed the second-grader. It also attacks healthy B-cells, so Emma needs to take immune globulins regularly in order to stave off infections. It is also extremely expensive, currently costing $20,000 - without a profit margin. Scientists remain uncertain about why it works and why it does not in some cases. Still, researchers are excited about the findings and hope to perfect it.

Dr. Carl June, who leads the research team at the University of Pennsylvania, ultimately hopes that the technique will eliminate the need for bone marrow transplants, which is now the last resort for people with Emma's kind of cancer.

The results have been mixed though. Three adults with chronic leukemia have since gone into remission with no further signs of the disease. One adult has been treated too soon for researchers to be sure about his progress. Four adults removed but did not fully go into remission, one child relapsed after the treatment, and in two adults, the procedure did not cause any progress whatsoever.

Still, even those not involved with the treatment say that it has great promise because it has worked in hopeless cases. Novartis, a major pharmaceutical company, has committed to $20 million for a research center that would be used to bring the treatment to market.

The treatment was first developed at the University of Pennsylvania and, while Emma received it at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, similar techniques are being used at the National Cancer Institute and the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.