Astronaut Scott Kelly Spent A Year In Space For Science; Here's What NASA Hopes To Learn From His Body

Astronaut Scott Kelly spent 340 consecutive days — an American record — circling the globe inside the International Space Station (ISS), all for the sake of science and future space travel. But why did Kelly spend so long floating in zero gravity, and what does NASA hope to discover after examining Kelly and comparing his body to that of his twin brother Mark, who spent the year safely on Earth? First, let’s look at everything NASA already knows about how space affects us, then let’s find out what the space agency hopes to learn from Kelly’s journey.

What We Already Know

People who spend extended amounts of time in space can suffer psychologically, which is why NASA submits all prospective astronauts to a series of rigorous tests to determine whether they’re capable of handling the journey. They look for good social skills, an easygoing demeanor, and the type of resilience that means the astronauts will be able to control themselves while cooped up in a bedroom-sized area for months at a time.

The ISS circles 249 miles above the surface of Earth. Astronauts who travel there can experience a phenomenon known as the “break-off,” which may be caused by isolation, their mental state, and even the way the ship is shaped. It can lead to sudden anger or a sense of being outside reality, according to Dr. Larry Young, Apollo program professor of astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

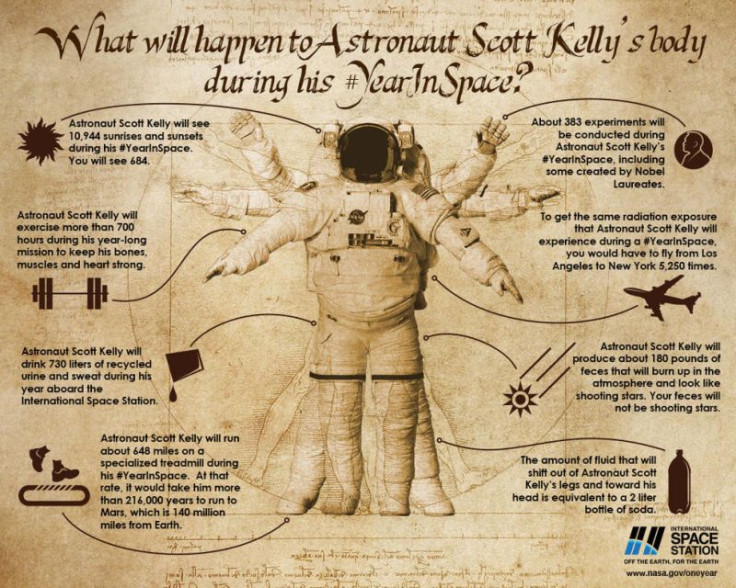

Physically, floating in zero gravity decreases overall bone strength, which means astronauts have to exercise in what Earthlings would call extreme amounts. Astronauts spend about two hours each day running and weightlifting using special machines that simulate gravity. Kelly spent about 700 hours lifting weights and ran about 648 miles while aboard the ISS.

What We Hope To Find Out

Gravity keeps the fluids in our bodies where they ought to be; once out of its grip, the fluids run rampant. As the infographic above shows, about 2 liters of fluid shifted from Kelly’s legs to his head over the course of the year. This shift may be the cause of a condition known as moon face — the puffiness in the cheeks of people who just got back from weightlessness.

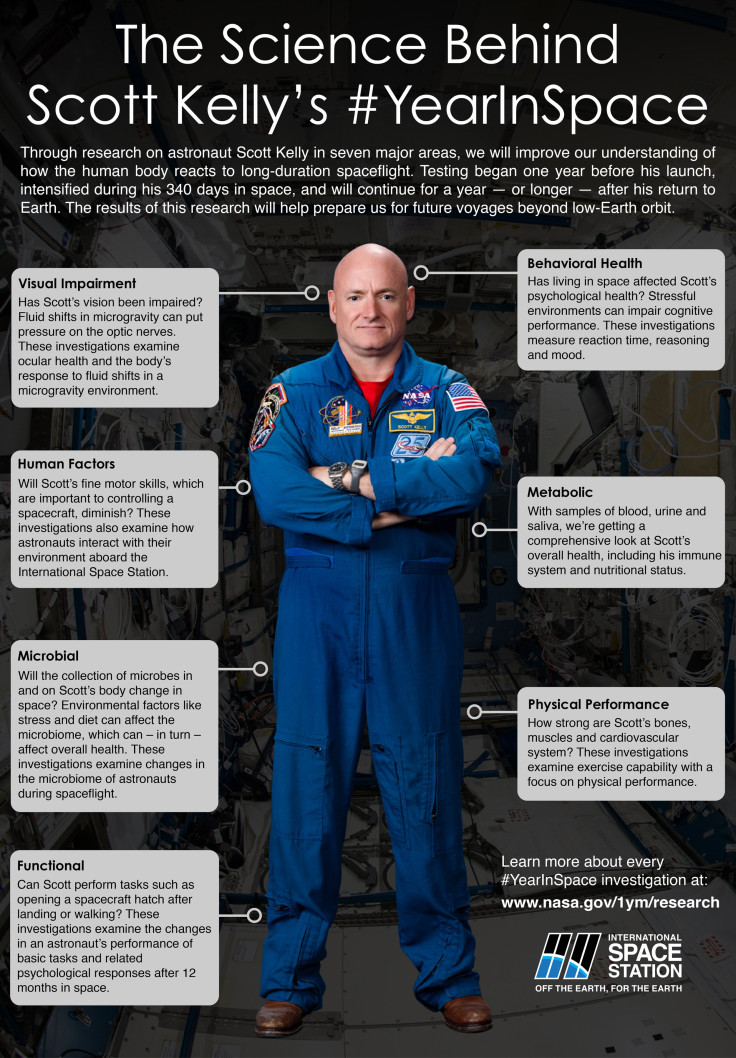

Shifting fluids in our bodies also spell trouble for our vision. Astronauts who return from lengthy trips in space reportedly come back slightly nearsighted. NASA believes fluid causes this as it pools around the astronauts’ brains, weighing on the optical nerves and deforming the eyeballs. To learn more, Kelly and his fellow astronauts underwent a fluid shift study and used a Russian Chibis suit, basically a pair of pants that use vacuum suction to mimic gravity, several times throughout the year. NASA monitored Kelly’s heart rate, vision, and body-fluid distribution throughout the process. While John Charles, Chief Scientist at NASA’s Human Research Program told Gizmodo that the experiment showed them something, more time is needed to analyze the data.

Radiation remains one of the biggest threats to humans in our quest to conquer space. Astronauts are constantly bombarded with it, even if their ships and the ISS are designed to shield them. Though NASA knows the dangers of exposure to too much radiation, such as an increased risk of cancer and even death, they used Kelly to find out if it alters our DNA.

This is where Kelly’s twin brother Mark comes into play. As we age, so do the telomeres on the ends of our DNA that protect our chromosomes from harm. Space travel might make our biological clocks move faster, meaning the telomeres age faster than normal, which can lead to mental problems later in an astronaut’s life. Seeing as the brothers have the exact same genetic code, NASA hopes to explore whether spending time in space caused any significant differences between them.

It will be a while before the results of Scott Kelly’s year in space come to fruition. But thanks to his journey, science may be better prepared for the trials and tribulations ahead as we reach out to the stars and beyond.

Published by Medicaldaily.com