In Search Of A Hair Loss Cure: How Close Are We, Really?

While losing a little off the top isn’t the social exile that it once was, the experience of hair loss is still stressful and frustrating for most people.

About 70 percent of men and 40 percent of women go through some degree of hair thinning as they age, almost usually as a result of androgenic alopecia (AGA), otherwise known as male or female pattern baldness. Though a number of products and treatments currently exist to fight back against hair loss, a so-called permanent "cure" would probably be one of the most exciting scientific discoveries to come along in a long time, right behind fat-free bacon and unlosable house keys. But is such a cure actually even possible? And if so, just how far from it are we?

Hair Today, Gone Tomorrow

By conventional standards, the current line of hair loss treatments are pretty damn effective, though ultimately limited in their capabilities. Finasteride (Propecia) and Minoxidil (Rogaine) are very safe medications that significantly boost and even regenerate our noggin’s capacity for hair growth.

For the short primer: Hair continuously grows out of a single follicle for a period of about four years, all the while being nourished by surrounding cells. The follicle then undergoes a short hibernation phase of about three months, recuperates, and sheds the current hair strand attached to it before starting production back up. At any one time, about 10 percent of our follicles are in that resting state while the rest are happily pumping out luscious tubes of keratin.

However, the cycle can be interrupted or made shorter by a number of things, including when blood levels of the androgen Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) are too high, such as with AGA, or when the immune system is mistakenly compelled to attack the follicle, such as with alopecia areata (AA). It can also be permanently shut down when follicles are damaged beyond repair (we’re born with all the hair follicles we’ll ever have, so once one is taken out of commission, that’s that).

Minoxidil circumvents hair loss largely by increasing blood flow (and nutrition) to the follicles, though it’s also believed to return some dormant follicles to a healthy state of growth. Finasteride, on the other hand, is a DHT inhibitor and restores a degree of normal function to the follicles. But both treatments need to be applied daily to work; have a limit to the amount of hair they can restore (they won’t work on permanently damaged follicles), and lose their effectiveness over time for a subset of users (Dutasteride, another more potent but off label DHT inhibitor, faces the same limitation).

Hair transplantation, where productive follicles from the rest of the head or body are seeded into the balding areas, is a more permanent option. Far from the old perception of fake-looking hair grafts, these techniques have become very good at replicating "natural" hair. In recent years, we’ve seen the advent of robotic technologies that aid the surgeon in precisely extracting and transplanting follicle grafts with minimal scarring. But these surgeries are plenty expensive, costing upwards of $10,000, can only shift around the amount of total hair you have, and don’t stop additional hair loss.

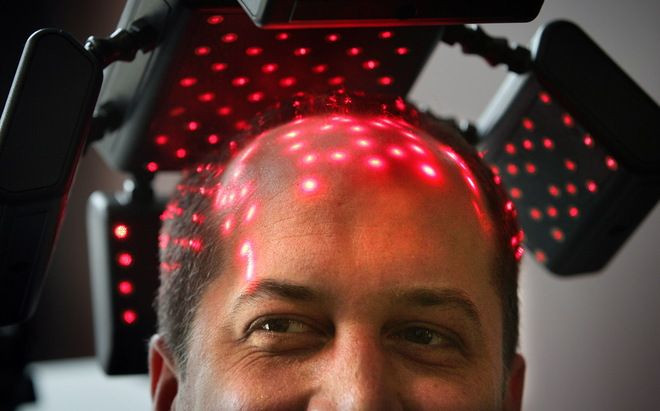

Other treatments, like low-light laser therapy, or nutritional supplements, have the barest of evidence or plausibility supporting their use.

Despair not though, embarrassed cap-wearing readers. As it turns out, there might actually be a bona-fide cure for hair loss already out there. Kind of.

Hair-Raising

About this time last year, the news was abuzz with the story of 25-year old Kyle Rhodes, a man whose head had become entirely bald, eyelashes included, because of his alopecia areata, first diagnosed when he was two. Like Lazarus rising out of a beauty salon, though, once Rhodes was treated with Xeljanz (tofacitinib), a drug ordinarily used for rheumatoid arthritis, his hair grew back after a scant eight months.

Funnily enough, his dermatologist, Dr. Brett King of Yale University, only prescribed the medication to help with Rhodes’ severe psoriasis, also an off-label use for the Pfizer-owned drug. "I was ecstatic," King told CNN. "I was truly overjoyed for him." He later published a study documenting Rhode’s hair recovery in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

"The results are exactly what we hoped for," King said in a statement released by the university. "This is a huge step forward in the treatment of patients with this condition. While it’s one case, we anticipated the successful treatment of this man based on our current understanding of the disease and the drug. We believe the same results will be duplicated in other patients, and we plan to try."

That same year, researchers in Nature Medicine announced their own hair miracle, as they reported that an oral preparation of the bone marrow cancer drug ruxolitinib had restored more than half of the hair lost by three balding AA patients after five months of treatment, validating their earlier animal studies.

Miracles rarely come without some caveats though. The drugs likely worked to reverse hair loss because of their immunosuppressive effects on the body, with both drugs belonging to a new class of drugs known as JAK inhibitors. At the time, neither Rhodes nor the patients in the Nature study reported any adverse effects, but it’s known that sustained use of these sorts of drugs can have severe drawbacks like an increased risk of infection — as anyone who has undergone chemotherapy can attest to.

It also isn’t known whether taking someone off these drugs will, like Rogaine, result in the hair falling back out yet. In a follow-up interview with WebMD, the authors of the Nature study explained that out of the dozen people they treated with ruxolitinib, only six out of nine experienced the miraculous hair growth they first reported (the last three hadn’t been on the treatment long enough to conclude anything at that time). Being a recent invention, these drugs would be also fairly expensive to regularly prescribe.

Some of these concerns can be mitigated should a JAK inhibitor ever be made available in topical form. At the time of his study, King hoped to pursue a clinical trial using a cream version of tofacitinib. And as of last October, the Nature researchers were eagerly looking to evaluate other JAK inhibitors in a placebo-controlled study. "Patients with alopecia areata are suffering profoundly, and these findings mark a significant step forward for them. The team is fully committed to advancing new therapies for patients with a vast unmet need," said study author Dr. Angela M. Christiano, professor in the Departments of Dermatology and of Genetics and Development at Columbia University Medical Center, in a statement.

Unfortunately, probably the biggest sticking point to these treatments is that they would likely do nothing for the majority of hair loss sufferers. AA, like rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis, is an autoimmune disorder, and the mechanism by which baldness happens in these people is different than what causes AGA — though it would certainly be a great boon to the approximately four million people in America suffering from AA.

No, to permanently cure baldness will undoubtedly take a much more radical approach.

'Unlimited' Hair

The major stumbling block to any hair loss cure is in restoring full functionality to our follicles, even those which have permanently become a Nair’d tundra. None of the current or proposed treatments we have available can pull that latter trick off.

Many researchers believe that the only way around this is to create new cells from scratch that stimulate hair growth for us, via stem cell therapy. Though stem cells, undifferentiated cells that can become a variety of specific cells, has been lauded as a potential means of regenerating organs or turning back the wheels of time, there’s logically no reason why they couldn’t also be turned into hair restorers.

Earlier this year, the authors of a PLOS-One study published this January may have made a giant leap in understanding how to accomplish that goal. From human pluripotent (embryonic) stem cells, they created cells that resembled dermal papilla cells, which reside underneath and regulate our follicles, and grafted them into the skin of albino mice. They discovered that these cells were able to stimulate hair growth.

What made their results particularly compelling was the fact that earlier attempts to use ordinary dermal papilla cells in grafting have come up short, due to their hair-simulating ability quickly fading away once removed from the body. It’s a shortcoming that the researchers believed they avoided by forcing the stem cells to pass through an additional transformation into a precursor stage of neural crest cells before finally becoming dermal papilla cells.

"Our stem cell method provides an unlimited source of cells from the patient for transplantation and isn't limited by the availability of existing hair follicles," said study author Dr. Alexey Terskikh, associate professor in the Development, Aging, and Regeneration Program at Sanford-Burnham University, in a statement at the time.

Though the research is only in the beginning stages, it "represents the first step towards development of a cell-based treatment for people with hair loss diseases," according to the authors.

"Our next step is to transplant human dermal papilla cells derived from human pluripotent stem cells back into human subjects," said Terskikh. "We are currently seeking partnerships to implement this final step."

Keeping It Healthy

In the meantime, while we’re waiting for that cure, there’s plenty we can do to ensure our hair health. As Medical Daily has previously reported, a healthy diet, exercise, and making sure your hair isn’t pulled too tightly by combs or hair ties will help maintain its cohesion. Similarly, should you notice it starting to wisp away, the best thing to do is to visit your dermatologist, since finasteride and minoxidil are much more effective when hair loss is caught early.

And as with most things, staying cool and collected will only help you in the long run. After all, one of the known causes of hair loss? Stress.