For Sperm, Being Slow Is Better Than Being Fast

For sperm, it was believed that it was better to be the hare rather than the tortoise It was widely believed the fastest swimming sperm usually succeed in its pursuit to fertilize the egg—until now. New research disproves that belief as nothing more than myth.

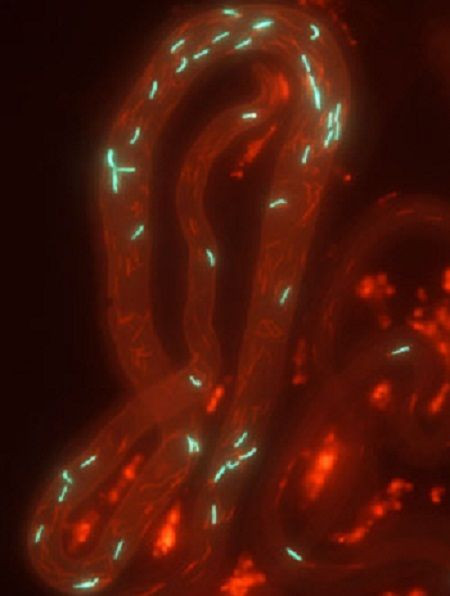

With the help of fruit flies, Stefan Lüpold, a post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Biology at Syracuse University, was able to monitor sperm in real time inside the female reproductive tract.

Biology professor John Belote genetically altered the fruit flies, so that the heads of their sperm would glow fluorescent green or red under the microscope.

“Sperm competition is a fundamental biological process throughout the animal kingdom, yet we know very little about how ejaculate traits determine which males win contests,” Lüpold says.

Researchers observed that female fruit flies mate approximately every three days. Sperm from each mating period swim through the female bursa into the storage area and remain there until the eggs are released. The egg will then travel from the ovaries into the bursa to await the sperm.

It is in the storage area where the sperm battle to fertilize the egg. After each mating period new sperm will try to throw out the sperm from previous mating sessions. The female will then eject the displaced sperm, completely eliminating previous sperm from the mating game. Additionally, it was also observed the longer slow moving sperm were better at replacing their rivals, which in turn they were less likely to be ejected from the storage, compared to their faster counterparts.

“The finding that longer sperm were more successful is consistent with earlier studies,” Lüpold says. “However, the finding that slower sperm also have an advantage is counterintuitive.”

Lüpold believes due to the sluggish movements of the sperm, it is less likely to hit the exit of the storage area, consequently reducing their chance of being ejected out.

The study was published in the journal Current Biology.

The U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and the Swiss National Science Foundation funded the study.