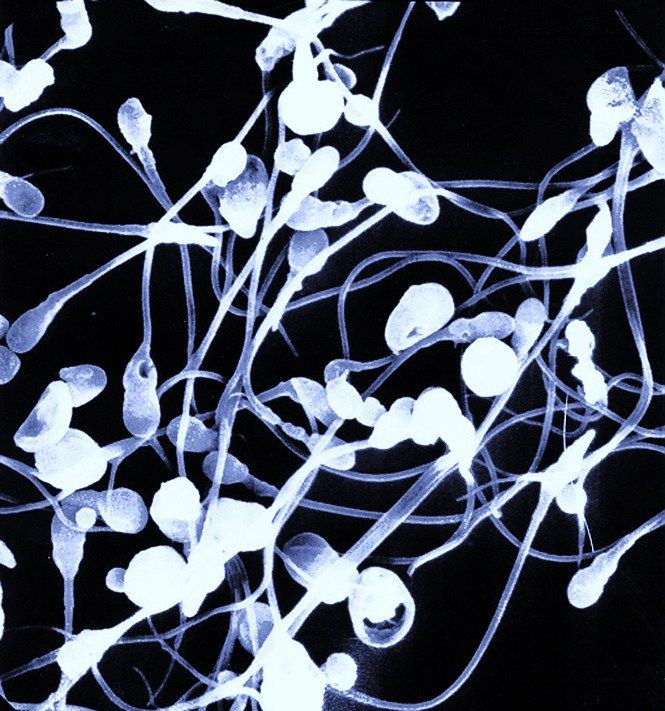

Sperm Rarely Swim, Instead They Blindly Crash and "Crawl" Their Way to the Female Egg

Scientists have discovered that contrary to popular belief, ejaculated sperm rarely swim, but instead fight and navigate through the complex female reproductive tract by 'crawling' along the channel walls, swimming, only rarely, around corners and repeatedly colliding into one another.

While millions of sperm cells are generally ejaculated at once, the few that actually reach the egg bump into each other frequently along the way.

A team led by Petr Denissenko, from School of Engineering at Warwick University and Jackson Kirkman-Brown, reproductive biologist at the University of Birmingham, studied sperm cell behavior by injecting the cells into hair-thin micro-channels or mini-mazes to determine which type of sperm were the quickest and why.

"In basic terms – how do we find the 'Usain Bolt' among the millions of sperm in an ejaculate. Through research like this we are learning how the good sperm navigate by sending them through mini-mazes," co-author Kirkman-Brown said in a statement.

"Sperm cell following walls is one of those cases when a complicated physiological system obeys very simple mechanical rules," researcher Denissenko, at the University of Warwick's School of Engineering, said in the statement.

"I study fluids in a variety of environments, but moving to work with live human sperm was quite a change,” he added. "I couldn't resist a laugh the first time I saw sperm cells persistently swerving on tight turns and crashing head-on into the opposite wall of a micro-channel.”

Despite popular imagery that the sperm make their way to the egg by smoothly swimming upstream, the latest findings suggest that their journey may be more sluggish and bumpy as they travel in the complex and intricate female channels that are filled with viscous fluids.

"When the channel turns sharply, cells leave the corner, continuing ahead until hitting the opposite wall of the channel, with a distribution of departure angles, the latter being modulated by fluid viscosity," researchers said. "Specific wall shapes are able to preferentially direct motile cells.”

Researchers said that the new findings, published Tuesday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, would help pave to way to future treatments that can help struggling or infertile couples that want to conceive.

Published by Medicaldaily.com