Spina Bifida Explained: Prevention Of This Birth Defect Begins With Moms-To-Be Eating Enough Folate

National Spina Bifida Awareness month is observed in October. Spina bifida is Latin and means “split spine.” Each year about 1,500 babies are born with spina bifida, according to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“As spina bifida and other birth defects occur during the first few weeks of pregnancy, it is critical that mothers plan their pregnancies so they can adopt healthy habits prior to becoming pregnant,” Dr. Kim Waller, an associate professor of epidemiology at The University of Texas Health Science Center, told Medical Daily.

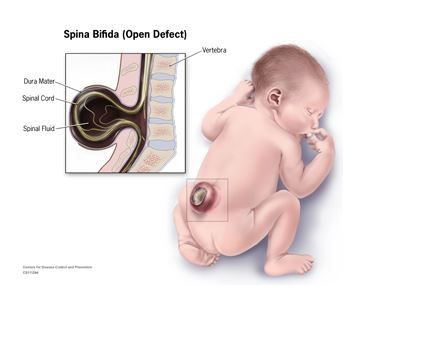

Spina bifida is classified as a neural tube defect. The neural tube begins to form early in a pregnancy, the Mayo Clinic explains; eventually it develops into a baby’s brain, spinal cord (a bundle of nerves running down the backbone), and enclosing tissues. Under normal circumstances, the neural tube closes during a pregnancy by the 28th day after conception. However, when a baby has spina bifida, a portion of the neural tube fails to develop or close properly.

In such a case, the spine becomes split in more than one vertebra and a sac forms on the outside of the baby’s back, Waller explained.

Types of Spina Bifida

Symptoms vary, depending on the severity of the defect and its location on the spine. Generally, Waller said, when spinal bifida occurs at the thoracic level or higher, this is associated with more disability. A lower level of spina bifida, say, on the lumbar spine or lower, is associated with less disability. The most severe defects can cause weakness, loss of bladder control, or even paralysis.

Meningocele is a rare form of the defect that causes a sac of fluid containing the protective membranes around the spinal cord to push through an opening in a baby’s back. Importantly, the spinal cord itself is not in this sac and so little or no nerve damage occurs. Because the spinal cord has otherwise developed normally, the sac can be removed by surgery with little or even no damage to nerve pathways.

Myelomeningocele, the most severe form of this defect, is also known as “open spina bifida.” Here, a sac of fluid pushes through an opening in the baby’s vertebrae — it contains part of the spinal cord and nerves, all damaged. Because tissues and nerves are exposed, the baby is prone to life-threatening infections. Myelomeningocele generally causes disability, including neurological impairment, which leads to bowel and bladder problems, loss of feeling in the legs or feet, muscle weakness of the legs, and sometimes paralysis, seizures, or orthopedic problems — such as deformed feet, uneven hips, and a curved spine.

What may be confusing to many people is a condition referred to as “hidden spina bifida” or spina bifida occulta. “Spina bifida occulta is a finding in about one percent of all back X-rays. It’s a little anomaly of the vertebrae, and not necessarily even related,” Waller said. “It’s not clear that it’s the same disease.”

This “defect” causes a small gap in one or more of the bones of the spine, without any damage to the spinal cord or nerves. Often it may not even be discovered until adulthood as it is only visible as a small dimple.

Treatment and Incidence

Treatment of spina bifida consists of surgically closing the opening in the baby’s back. Certain cases are appropriate for and treated with fetal surgery; however, if not treated in the womb, a baby will undergo surgery after birth, Waller explained. Most babies also require occupational therapy following surgery to assist them with walking and mobility.

Through fetal surgery and improvements in neonatal surgeries overall, the percent of infants who are able to walk increases all the time, according to Waller.

Though the cause of spina bifida is unknown, some families have a history of neural tube defects. Compared with white mothers, for example, Hispanic mothers are more likely to have infants with spina bifida, a number of studies have found. One 2012 study, led by Dr. A.J. Agopian, assistant professor of epidemiology at UT Health, clarified prevalence rates. Agopian and his colleagues found Hispanic mothers have a higher risk of almost all subtypes of spina bifida compared to white mothers, and black mothers have a lower risk of most types of spina bifida compared with white mothers.

In descending order, the rate for Hispanic women is 4.17 per 10,000 babies, 3.22 per 10,000 babies for white mothers, and 2.64 per 10,000 for black mothers, according to the CDC. While this may suggest genetics plays a role, Waller noted that it more likely is the result of a complex blend of environmental and genetic factors.

An important environmental risk factor is folic acid deficiency.

Folic acid, a B vitamin that cells need to grow and develop, reduces the risk of spina bifida and other neural tube defects. Folic acid is often listed on food packages as “folate,” March of Dimes explains. Since 1992, national guidelines instruct all women of childbearing age to take 400 micrograms (mcg) of folic acid each day as a supplement. In January 1998, the Food and Drug Administration mandated adding 400 mcg of folic acid per serving to bread, pasta, rice, and breakfast cereals. Since fortifying grains in this way, the prevalence rate of spina bifida has declined 31 percent in the United States, according to the CDC.

Ultimately, women can decrease their chance of having a baby affected by spina bifida by taking a daily multivitamin, maintaining a healthy weight, and avoiding unusual or extreme diets before they become pregnant. “It is critical that mothers plan their pregnancies before becoming pregnant,” Waller said, adding that women need to focus not just on pregnancy care but on pre-conception care. “That’s a difficult thing for people to do,” Waller said.

Published by Medicaldaily.com