Stem Cells Safe For Use In Regenerative Medicine: Researchers Incorporate Human Pluripotent Cells In Embryo

There’s been a big victory for stem cells, and it could have important implications for regenerative medicine: Researchers have found the strongest evidence to date that human pluripotent cells will develop normally and safely once transplanted into an embryo.

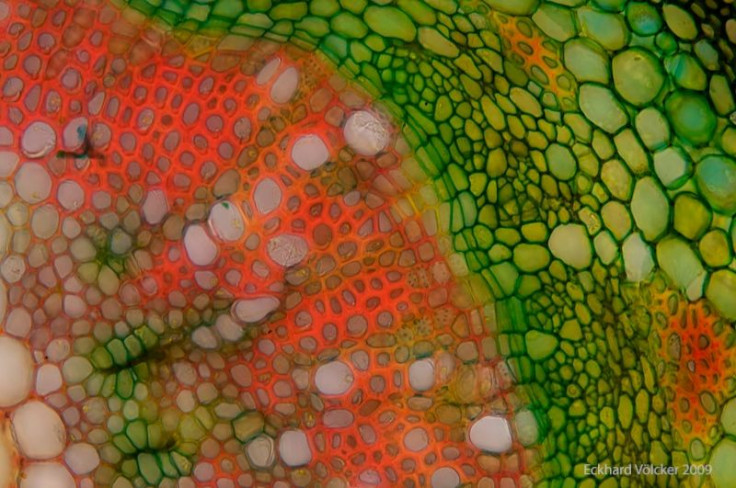

Pluripotent cells have the potential to become every tissue in the body, an invaluable ability for regenerative medicine and biomedical research. Human pluripotent stem cells are derived from two sources: embryonic cells, which come from fertilized eggs discarded from IVF procedures; and induced pluripotent stem cells, skin cells that scientists have "reset" to their original pluripotent form. These cells are seen as having promising uses in therapeutic, regenerative medicine to treat serious conditions — most notably in those organs that have poor regenerative capability, like the heart, brain, and pancreas.

Despite their many virtues, the human pluripotent stem cells are a cause of concern for many scientists, who believe the cells may not incorporate into the body properly, and not distribute themselves as intended. This could result in tumors, an obviously negative consequence.

A new study out of the University of Cambridge suggests that this won’t happen, and that stem cells, when implanted properly, will most likely be safe for use in regenerative medicine.

"Our study provides strong evidence to suggest that human stem cells will develop in a normal — and importantly, safe — way," said Professor Roger Pederson from the Anne McLaren Laboratory for regenerative Medicine at the University of Cambridge, in a statement. "This could be the news that the field of regenerative medicine has been waiting for.”

Passing The Test

Researchers’ best bet for understanding how stem cells would incorporate into the body is to transplant them into an early-stage embryo and track how they develop. It’s unethical to attempt this with human embryos, so scientists generally use those of mice. Cambridge developed the gold standard test for the process in the 1980s, which involves inserting stem cells into a mouse blastocyst (a very early stage embryo) and assessing the stem cell contribution to the various tissues of the body.

Past research had never succeeded in getting human pluripotent stem cells to effectively incorporate into the embryos. Pederson and study co-author Victoria Mascetti have finally shown that it is possible to successfully transplant human puluripotent cells into a mouse embryo, resulting in normal growth and development.

“Stem cells hold great promise for treating serious conditions such as heart disease and Parkinson’s disease, but until now there has been a big question mark over how safe and effective they will be,” Pedersen said.

Attempts to incorporate the cells had failed previously, due to the stem cells being inserted at the wrong stage of embryo development. The cells actually needed to be transplanted into the mouse embryo at a later stage than previously thought, so once they were transplanted at the correct stage, the cells went on to spread normally, integrating into the embryo and proliferating across all relevant tissues.

“Our finding that human stem cells integrate and develop normally in the mouse embryo will allow us to study aspects of human development during a window in time that would otherwise be inaccessible,” Mascetti said.

Professor Jeremy Pearson, the associate medical director at the British Heart Foundation, which funded the study, added that the results strengthen the idea that induced pluripotent stem cells are a good choice for regenerative medicine.

“The Cambridge team has shown definitively that when stem cells are introduced into early mouse embryos under the right conditions, they multiply and contribute in the correct way to all the cell types that are formed as the embryo develops,” he said.

Source: Mascetti V, Pedersen R. Human-Mouse Chimerism Validates Human Stem Cell Pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. 2015.