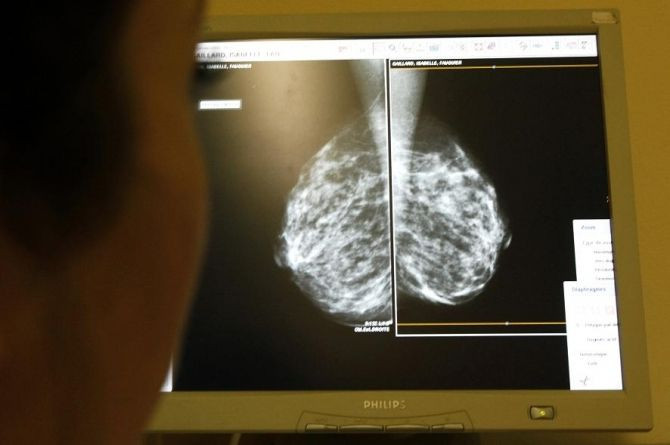

Study Links Mammograms to Overdiagnosed Breast Cancer Cases

Up to a quarter of breast cancer tumors detected by mammograms are overdiagnosed, and would have never caused symptoms, according to a new study.

Researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health conducted a study with 39,888 women in Norway with invasive breast cancer, including 7,793 that were detected after routine screening began, and found that between 15 and 25 percent of breast cancers detected by screenings led to unnecessary treatment such as surgery, chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

Researchers compared the number of breast cancer cases in women who had been offered screening to those not offered. They had predicted that if mammography screens were beneficial, there should be lower rates of late-stage breast cancer cases because early detection would in theory prevent late-stage disease.

The findings show there was no significant reduction in late-stage disease in women who had been screened, but instead a significant number of overdiagnosis. They found that while one death would be prevented for every 2,500 women offered screening, about six to ten women would be treated for a benign cancer that would have never caused symptoms.

Most women in the U.S. begin having annual mammograms beginning in their 40s and 50s, but scientists from the latest research said that the accumulating evidence of overdiagnosis from screening, which can cause unnecessary stress and medical treatment, suggest that mammography might not be effective for breast cancer screening.

"Mammography might not be appropriate for use in breast cancer screening because it cannot distinguish between progressive and non-progressive cancer," said study author Dr. Mette Kalager of the Telemark Hospital in Norway in a statement released on Monday.

"Radiologists have been trained to find even the smallest of tumors in a bid to detect as many cancers as possible to be able to cure breast cancer. However, the present study adds to the increasing body of evidence that this practice has caused a problem for women—diagnosis of breast cancer that wouldn't cause symptoms or death," Kalager added.

Researchers recommend that women be informed not only about the potential benefits from mammography but also about its potential harms.

"Overdiagnosis and unnecessary treatment of nonfatal cancer creates a substantial ethical and clinical dilemma and may cast doubt on whether mammography screening programs should exist. This dilemma can be reduced only when potentially fatal cancer that requires early detection and treatment can be reliably identified," the authors wrote.

Researchers said that because screening started earlier in the United States than in Norway, where the study took place, overdiagnosis probably occurs more frequently in the U.S., according to Dr. Joann Elmore, of the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, and Dr. Suzanne Fletcher, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, in an accompanying editorial.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force in 2009 revised their previous breast cancer screening guidelines and recommended that women ages 50 to 74 receive a mammography every two years, against their old guidelines that advised that women in their 40s get screened annually.

The latest USPSTF guidelines spurred controversy among physicians, advocacy groups and in the media, and many groups such as the American Cancer Society and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists still follow the old USPSTF guidelines, and recommend yearly screenings for women beginning the age of 40.

Researchers from the latest study noted that overdiagnosis and overtreatment could be reduced if doctors had tools to distinguish between cancers that are likely to process and those that are benign, but currently those tools still do not exist.

"Nevertheless, unless serious efforts are made to reduce the frequency of overdiagnosis, the problem will probably increase," as new imaging techniques are introduced, Elmore and Fletcher wrote in the editorial.

The study was published in the April 3 issue of the Annals of Internal Medicine.