Racism And Sexism In Academic Medicine Skew Health Care For Women, POC

It was 1908 when playwright Israel Zangwill first referred to America as a melting pot, a destination where people of different backgrounds and cultures could tough it out alongside each other and come out better for it. Come out an American. Now, his message resonates in a whole new way. In 2013, racial and ethnic minorities surpassed non-Hispanic whites as the largest group of American children younger than five years old; by 2044 the white majority in the United States is expected to be gone.

Women have also become a majority group, according to the 2010 census. The bureau reported they outnumbered men 157 million to 151 million, and among people aged 85 and older, there were more than twice as many women as men. The wise Ilana Wexler — the character comedian Ilana Glazer plays on Broad City — said it best: “Statistically, we’re headed toward an age where everybody’s going to be, like, caramel and queer.” Insert double peace sign.

And yet, at a time when non-white Americans bear the majority of the country’s disease burden, women and people of color remain underrepresented in clinical research. In 2004, women made up less than a quarter of all patients enrolled in 46 examined clinical trials, Slate reported. A more recent study published in Cancer found Hispanics and blacks participated in 1.3 percent of cancer clinical trials despite experiencing higher rates of disease than whites. This means that the counsel and care these two majorities receive comes secondhand — it is still largely designed for white men. Even in animal studies, there’s a bias toward males.

The exclusion suggests we’re all the same — a nice idea in terms of unity, but a reckless one when it comes to health care. Treatment is not universal, and in order to target effective therapies and medications, researchers have to consider sexual and racial differences. More than that, they have to face the fact that racism and sexism runs the whole gamut of medicine: In trials, in grant applicants, and in the classroom. Admitting there’s bias, as uncomfortable as that may be, is the only way we can truly work to eliminate it.

Vulnerable and abused

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) made two moves in the early 20th century that would inadvertently set a precedent of exclusion for women and people of color.

The first grew out of the 1938 U.S. Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which subjected every new drug to evaluation before it could be sold to consumers. The law didn’t specify the kinds of tests needed for approval, but it did allow officials to block new drugs because of insufficient data. In 1962, FDA inspector Frances Kelsey exercised this right when her supervisors and a pharmaceutical company tried to bring thalidomide over from Germany, where it had been approved in the late 50s to treat skin disease caused by leprosy. She was motivated by the news that children born to pregnant women taking the drug had severely deformed limbs, and because there weren’t any results available from U.S. clinical trials. This led to the 1962 drug amendments, which explicitly mandated scientific testing to substantially prove a drug’s safety and efficacy.

Soon after, the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research issued federal regulations that limited the extent to which both pregnant women and fetuses, and women with childbearing potential could participate in studies, labeling them “vulnerable populations,” a classification that has been criticized for its implication that women are incapable of making responsible decisions for themselves and their future offspring.

Similarly, when psychiatrist and neurologist Dr. Leo Alexander wrote the Nuremberg Code after studying the actions of German SS troops and concentration camp guards, agencies like the FDA used it as a prototype for their individual guidelines concerning human research subjects. The code recommended that every person involved in a study should have the legal capacity to give consent, be able to exercise their free will, and be free to end an experiment at any time. Some parts were more specific than others, ultimately leaving room for interpretation. Without formal regulations, mistreatment slipped through the cracks, leading to many abuses of the elderly, the weak, and African Americans.

One infamous example was the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male,” in which 600 African-American men were told they were being treated for "bad blood," or ailments like syphilis, anemia, and fatigue. The study first began in 1932 but, as it later come to light in 1972, the men weren’t receiving any treatment at all, not even when penicillin was approved as an effective treatment for syphilis.

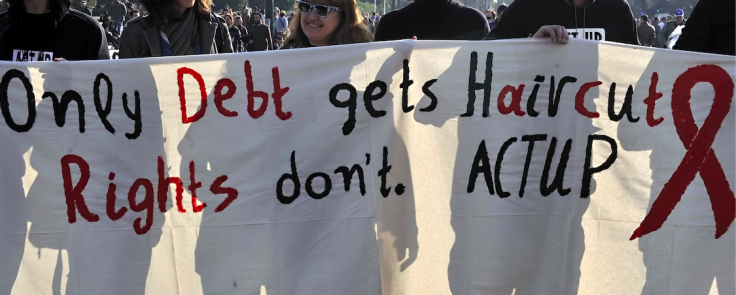

The FDA worked out the kinks of what were foundationally good policies, but these changes were motivated by public outcry. A German newspaper broke the story of thalidomide’s link to severe birth defects, and the Associated Press was the first to question the Tuskegee study. It took an outside force to protect women and people of color, a similar pattern repeated in the AIDS activism of the ‘80s and ‘90s — only in that instance, activists gave women and people of color license to cultivate a voice all their own and prove diverse research benefits us all in the end.

On the cutting edge of change

There are two mainstream examples of diversity in clinical research: the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) and the ongoing Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) study. That they began within less than a decade of each other, at the end of the 20th century, suggests inclusivity once had momentum — but that movement has since stalled. They remain the only large-scale studies to tackle diversity in a real way. The methods that made each study successful, though, could be roadmaps for future endeavors.

The WHI began in 1993, right on the heels of the AIDS movement. “We know that women’s issues didn’t get attention until they got a voice,” principal investigator Dr. Garnet Anderson told Medical Daily. ”It was a primary marker of the activists who learned how to push to get research done.”

When the National Institutes of Health (NIH) sponsored the WHI, which focused on strategies to prevent heart disease, cancer, and bone fractures in postmenopausal women, they made it a goal from day one to include a racially and ethnically diverse population representative of older American women at that time. The goal was for 17 to 18 percent of the total sample to be minorities. They achieved this by setting up 10 of their 40 clinical centers in diverse areas of country. Before that they had only managed to attract 5 percent or less, Anderson said.

The NIH again encouraged this inclusivity when it sponsored the MESA study in 2000. Of the more than 6,800 men and women aged 45 to 84 they’re studying, 38 percent are white, 28 percent African-American, 22 percent Hispanic, and 12 percent Asian, predominantly of Chinese descent. The study is designed to better understand new imaging technology and whether it predicts heart attack and stroke better than traditional risk signs, principal investigator Dr. Gregory Burke, who was also involved with the WHI, told Medical Daily.

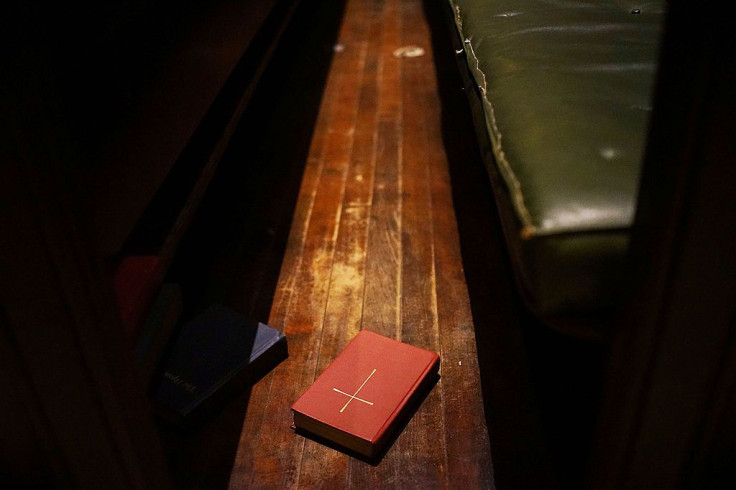

Both studies prove that when you make inclusivity a primary goal, you get a diverse sample of participants because you set up a study structure already built for success, Anderson said. And, as demonstrated by the WHI, when you put research projects directly in affected communities, it increases participation engagement and offers valuable insight on how to include them in the overall research agenda. For example, communities of color “are less enamored with traditional science and technology,” Dr. Janet L. Mitchell first suggested in a paper she wrote for the Institute of Medicine. Instead, they’re more likely to turn to spirituality and alternative treatments; in which case it’s no surprise Anderson sent some recruiting investigators to faith organizations. Overall, researchers are finding that religious associations are a better avenue for recruitment than traditional media, posters, and telephone contacts.

“Spirituality is seen as a major cornerstone in the foundation for survival,” Mitchell said. “It is especially called upon when one is faced with life-and-death crises, such as a terminal illness.”

On the other hand, the extensive follow-up the MESA study has incorporated into its five exams so far addresses another barrier women and communities of color face, according to Mitchell: loss of income and lack of time.

“While there is a growing middle class in communities of color, there is still a gap in the earning potential and job status,” she explained. “The middle class status of many families is dependent on two incomes or multiple jobs. The job position may not allow for much flexibility. This translates for many into loss of income for the time needed for follow-up or the inability to find the time for follow-up because of multiple responsibilities.”

And since women traditionally fall into the roles of caregiver and caretaker, they are more likely to put another person’s needs before their own. A successful program will recognize that.

Calling out preconceived notions and bias

Ileana L. Piña, a cardiologist at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore-Einstein Medical Center in the Bronx, a borough of New York City, didn’t learn about adversity and disparity in health care when she was in medical school, she previously told Medical Daily — she learned it on her own, motivated by her identity as a Cuban woman. Mitchell could probably relate. When the NIH asked her what her biggest career obstacle was, she said her gender.

“When I applied for residency [to be an OB-GYN], there were programs that did not take women,” she recalled. “Even my interview at Harlem Hospital, I was told of the five slots for residents, they only took one woman a year.” This was 1988.

Today, 47 percent of students in academic medicine are women, but they still only hold 24 percent of science, technology, engineering, and medical-related career jobs, according to a report from the U.S. Department of Commerce. What’s more, as David Kaplan suggested in an article for Scientific American, the NIH grant process may unintentionally discriminate against women and nonwhites.

The basis for Kaplan’s theory is a 2011 study from the University of Kansas that found only 16 percent of applications from black researchers were funded, while 29 percent of those from whites were. Lead study author Donna Ginther said the effect “probably has many causes, such as the level of education and mentoring white scientists received compared to their black peers. The two may give the former applicants an edge over the rest.”

Kaplan had another idea.

“One possible explanation is that NIH peer review is structured to promote bias not so much against a racial group as against the unfamiliar and unconventional,” he wrote. “Expert reviewers are asked to provide detailed assessments of long, highly complex, extraordinarily technical documents, and they are given little time to do it. The reviewers are usually conversant with the specific area of research that the proposal addresses, which means that they come to the application with preconceived notions. Short deadlines encourage them to rely on established knowledge and sensibilities. In this scenario, reviewers are more comfortable with proposals from scientists they are familiar with — scientists they either know or know of.”

The same could be said for the diseases themselves, Kaplan continued. He suggested grant applicants’ ideas may seem “unconventional” if they target rare diseases like sickle cell anemia , a blood disorder that disproportionately affects Black and African-American men. On the other hand, an applicant might get farther with a study on melanoma — also a rare disease, but the leading cause of skin cancer deaths.

The American Heart Association recognized a similar problem with the state of heart disease research in the early 2000s. Since the condition was believed to only affect old men, no one knew what to do with new data that showed it was now greatly affecting women. As a result, they launched the Go Red For Women Campaign to help women learn the facts about heart disease, which can manifest differently in females than in males. The campaign also encourages women to get involved and to take legislative action on behalf of themselves and others.

More of these grassroots campaigns are popping up throughout the country: Trust Black Women is working with Black Lives Matter to “develop a strong network of African-American women organizations and individuals mobilized to defend” reproductive rights, according to their mission statement. The Fortaleza Latina project aims to develop a multilevel breast cancer intervention for a sample of Latino women living in western Washington.

Scientists apply for research grants because clinical study is expensive. It’s an arduous process, so if a team focuses on a specific hypothesis, then diversity efforts may fall by the wayside, Anderson said. It costs money to set up clinical centers in minority communities, a luxury the WHI could afford. But health care shouldn’t be a privilege.

What comes next

Systemic racism and sexism is alive and well in the U.S., though many will disagree — at the very least they’ll be uncomfortable confronting that bias. A study published in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology found that when white people are faced with this reality, as well as the idea that their group benefits from privilege, they fail to take responsibility and claim hardships to protect their self-image.

In his coverage of the study for Pacific Standard, staff writer Tom Jacobs suggests it’s easier to deplore the bad things rather than face the music because, historically, “Our national mythology insists we live in a meritocracy, and we’re reluctant to believe otherwise — especially when the playing field is tilted to our advantage.” A meritocracy may be the ideal melting pot; a country that’s led by the best and the brightest. But it’s only an ideal. The data shows, or rather doesn’t show, women in science, technology, engineering, and medicine. Black researchers with NIH grants. Either group in clinical trials.

“There’s awareness of it at the government level, by scientists, that we want [diversity],” Burke said. “The challenge is that it just doesn’t happen. You have to purposefully identify how you’re going to recruit a diverse sample. You want to make sure you have data that can be applied more universally.”

For Burke, that means thinking more about tailored outreach efforts in communities of color, as well as in medical schools. And for Anderson that means going directly to the source.

“We need to do a better job training more minority young people to become [investigators], to get more young people interested in science and medical research,” Anderson said. “They are the ones that are going to have the trust of [their] populations. They are going to be the leaders of the next generation."