With Climate Change, Ticks Are Moving On Up, Spreading Lyme Disease And Other Tick-Borne Diseases To New Parts Of The Country

With the summer approaching quicker than you can say ‘beach bod’, the fear of shark attacks will inevitably rear its sharply pointed head again. Yet for all the hubbub surrounding them, the actual frequency of attacks in the United States is, and has remained, embarrassingly low. Only 53 authenticated, unprovoked attacks were documented in 2013, according to the Shark Research Institute.

No, when it comes to clear and present dangers from summertime wildlife, the fearsome shark pales in comparison to an eight-legged creature several orders of magnitude smaller than it, the tick. While their bites might be gentler, the variety of pathogens they can spread with each one, including those responsible for Lyme Disease, sure aren’t. And if the recent warnings from Indiana University Bloomington (IUB) researchers bear any fruit, these ticks’ sphere of influence will only grow in size as our climates get warmer.

A Rising Tide

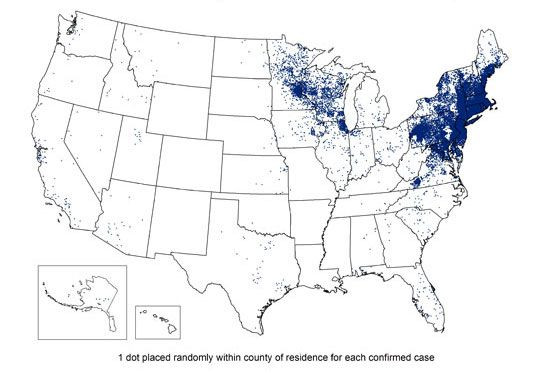

Though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have reported an annual 20,000 to 30,000 cases of Lyme disease for the past decade, they themselves caution that their numbers are likely a severe underestimation of the true prevalence of Lyme, mostly caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi through the bite of a black-legged tick (Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus). In its announcement of May as Lyme Disease Awareness Month, the CDC explained that research shows as many as 300,000 cases of Lyme are treated and diagnosed every year.

But Lyme isn’t the only disease spread by ticks. While Lyme is generally only seen in the upper midwest, New England, and the mid-Atlantic states, cases of southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI) dot the eastern, southeastern and south-central states, spread by the lone star tick, Amblyomma americanum. These ticks have also been linked to a string of newly discovered ailments, including the Heartland virus in Missouri, and its saliva alone is believed to inexplicably trigger a meat allergy in certain individuals.

Not to be outshone, the Ixodes family of ticks has been connected to outbreaks of babesiosis and Powassan virus disease. These diseases vary in their severity, but range from crippling fatigue months after antibiotic treatment to permanent neurological damage and even death. The diversity of illnesses that can be spread via ticks easily makes them the most influential disease vector in the U.S., second only to the mosquito worldwide.

And according to Dr. Keith Clay, Distinguished Professor in the Indiana University Bloomington College of Arts and Sciences' Department of Biology, we're only becoming more intimate with them. "Just in the past 10 years, we're seeing things shift considerably," Clay said in a press release by the college, "You used to never see lone star ticks in Indiana; now they're very common. In 10 years, we're likely to see the Gulf Coast tick here, too. There are several theories for why this is happening, but the big one is climate change."

The research conducted by the Clay Lab at IUB has broadly examined how interactions between organisms, especially microorganisms, can influence the ecology of a community, or even that of an individual species. It has been their efforts in studying the microbial world inside ticks that have allowed them to see shifting patterns of movement among their populations. “In Indiana, the black-legged tick is invading from the north while the lone star tick is invading from the south,” Clay Lab researchers wrote.

Other research has echoed similar conclusions, albeit about different parts of the world. "The number of known endemic areas of Lyme disease in Canada is increasing because the range of I. scapularis is expanding in the eastern and central provinces," a 2009 study from the Canadian Medical Association Journal concluded. And the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), in a section evaluating the possible impacts climate change may have on human health, notes that marked increases of the tick population in North America and Europe have been observed over the past two decades, with some evidence showing a correlation between milder winters in Sweden from 1980 to 1994 with an influx of tick growth.

No Smoking Gun

Despite all that, it’s still too soon to declare a smoking gun connection between climate change and tick-borne illnesses. In a 2015 review published in Philosophical Transactions B, the authors note that while many studies have found evidence for a link between warming temperatures and tick-borne illnesses spread by the black-legged tick, there are too many overly simplistic assumptions made by these studies to be able to reach any concrete conclusions.

Some research has relied on laboratory methods to replicate the best environmental conditions for tick growth, but it can be difficult to translate their results to a real life setting. The authors specifically point out that while a location might be arid and dry, conditions unfavorable for the black-legged tick, they can find humidity in leaf litter or soil. And attempts to create theoretical models of tick growth based on a variety of environmental factors can result in vastly different conclusions, the authors noting that while one model predicted a westward migration of ticks with climate change, another predicted that incidences of Lyme would vastly increase in the eastern and Midwestern areas of the United States.

In other words, while it’s likely that warming temperatures have and will spread ticks to more parts of the world; we don’t have a firm grasp of how and where exactly this will happen. And we won’t until we establish a better standard of research that accounts for the complicated interactions of climate on not only tick, but human, pathogen, and other host animal populations, the authors warn. "An understanding of climatic impacts on the vector and pathogen will allow researchers to predict how risk of human exposure to these pathogens will change as the climate continues to change," they wrote.

For their part, the Clay Lab has attempted to understand how the microbial environment, commonly referred to as the microbiome, of a tick can influence not only its life cycle, but possibly even fight against the emergence of disease-causing pathogens by increasing the amount of non-disease-causing microbes known as symbionts found in a tick. "Understanding the tick's microbiome is really laying the foundation for future research," former Clay Lab graduate student and current postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Edinburgh Evie Rynkiewicz said, "There are groups working right now on introducing symbionts into mosquitoes' microbiome to block or reduce the number of pathogens in their systems that affect humans. One day we may be able to do the same with ticks."

Regardless of where these advances in research may bring us someday, perhaps the most important lesson to take away is in being aware of the practical steps we can take to prevent tick-borne illnesses in the first place. As per the CDC, simple tips include avoiding areas with tall grass and brush where ticks are known to reside; using repellents with at least 20 to 30 percent DEET; showering soon after coming indoors as well as conducting a full body check for ticks; and seeking medical attention if symptoms like fever, rash and muscle and joint pain develop.

Now if only we could get the Discovery Channel to sponsor Tick Week.

Published by Medicaldaily.com