Tragic Photos Show How Zika Damages Babies' Brains

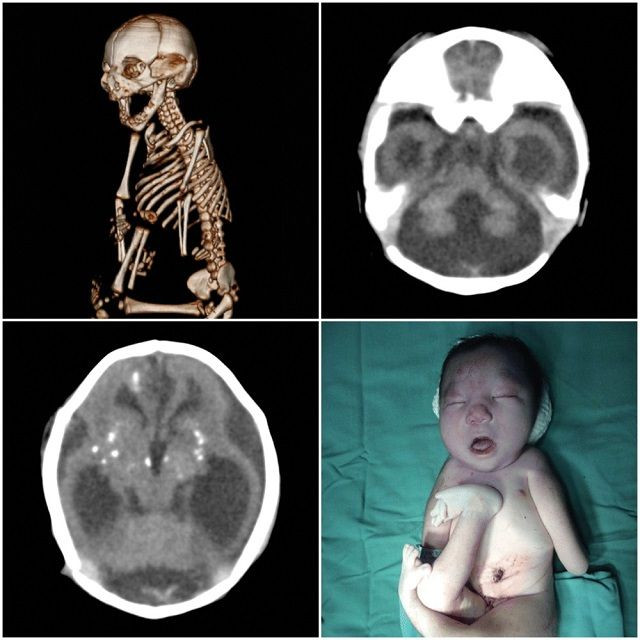

An exhaustive study of Zika-infected babies released in Radiology reveals the extent of destruction that the mosquito-borne virus causes to their developing brains.

The international coalition of researchers reviewed the brain scans and ultrasound photos of 45 babies either confirmed or strongly suspected to have been infected with Zika while in the womb. The images, obtained from the Instituto de Pesquisa in Paraiba, Brazil, display a wide array of neurological and physical deformities — from calcified and shrunken regions of the brain to fluid-filled ventricles on the verge of bursting. Importantly, they also reaffirm that the appearance of microcephaly, or a much smaller-than-normal head, is not the only problem for these unfortunate children. The results suggest that it may take years before doctors can be sure how exactly Zika infection will affect their development growing up, and children born with seemingly normal-sized heads may still suffer silent brain damage.

“It’s not just the small brain, it’s that there’s a lot more damage,” study co-author Dr. Deborah Levine, a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School in Boston, told The New York Times. “The abnormalities that we see in the brain suggest a very early disruption of the brain development process.”

Like previous research reported by Medical Daily, they also found that several children had come down with joint contractures as a result of Zika infection. The contractures, possibly formed by the brain’s inability to communicate with the affected muscles, could leave the children with frozen limbs, unable to walk.

For several of the children, the scans revealed a particularly disturbing consequence of Zika infection: Their brains had stopped growing at some point, but the rest of their heads hadn’t, leaving the skin on top of their skulls folded into itself.

“There’s too much skin for the size of the head,” Levine said.

Three infants didn’t meet the medical definition of microcephaly, but at least in one case, it was only because the virus caused obstructions in the brain, causing certain cavities to fill up with cerebrospinal fluid and the head to swell up, according to Levine. This build-up likely destroys areas of the brain as fetuses develop and then decompresses, helping cause the shrunken head appearance of microcephalic infants. For infants who still have fluid-filled ventricles, though, the burst may only occur later in life, leading to the collapse of the brain. Of the 17 infants with confirmed infections, 3 had died soon after being delivered.

The sample studied by Levine’s team isn’t perfectly representative of all congenital Zika infections, and may only reflect the most severe cases. Nearly all the confirmed infections in the study were found in infants whose mothers had developed a telltale rash, for instance, but not all cases of congenital Zika have reported the same. What is likely certain is that Zika does its worst to developing fetuses in the 1st trimester of pregnancy, and the earlier the worse. But we still don’t really know how likely the chances of an infected mother passing the virus to her child are, and whether the risk or severity of infection is lower in those moms who present no symptoms. These symptomless carriers account for about 80 percent of all Zika patients.

Levine and her colleagues hope their findings, made available free of charge, can help create a sort of roadmap for future doctors and radiologists as the Zika epidemic continues to spread across the world.

Source: Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld P, Levine D, Suely de Oliveira Melo A, et al. Congenital Brain Abnormalities and Zika Virus: What the Radiologist Can Expect to See Prenatally and Postnatally. Radiology. 2016.

Read More:

Zika Virus May Cause Joint Deformities, As Well As Microcephaly, In Newborns. Read here.

The ‘New Normal’: How Zika Virus Will Affect The Mental, Physical Health Of Children In The Americas. Read here.