Type 2 Diabetes Begins With Bacterial Infection, Suggesting Room For A Vaccine

Scientists working in rabbit models have recreated the hallmark symptoms of type 2 diabetes using a common strain of bacteria found on the skin’s surface, a new study reports. The findings could pave the way for anti-bacterial treatments and vaccination against microbial invaders.

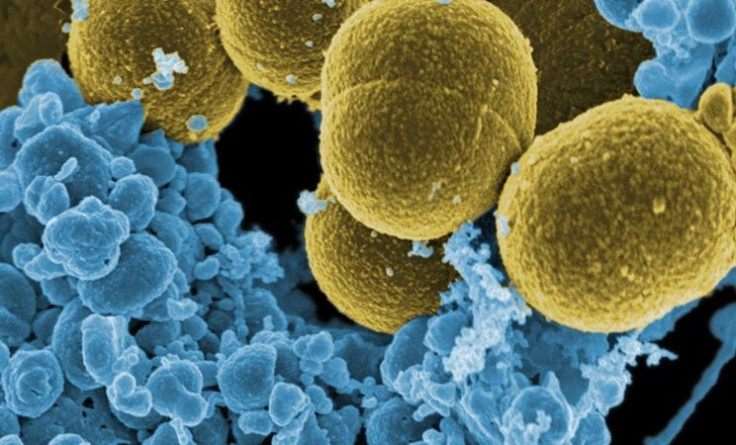

Between 90 to 95 percent of diabetes cases are type 2 diabetes, an insulin deficiency that develops through lack of exercise and poor diet. This has led to the widespread belief that obesity poses direct risks to developing the disease; however, the new research suggests an alternate route to diagnosis, namely, the Staphylococcus aureus (staph) bacteria living on the surface of the skin.

“At any given time, 30 percent of folks are colonized in the [nostrils] and other mucosal surfaces with S. aureus, with nearly all of us occasionally colonized,” Dr. Patrick Schlievert, the study’s senior author and professor of microbiology at the University of Iowa College of Medicine, told Medical Daily in an email. As people gain weight, their skin effectively becomes “wetter” due to increased sweating and greater skin folds, making an ideal home for bacteria to colonize and enter the body. “We find that the colonization rate goes up to 100 percent.”

Schlievert and his colleagues recently wanted to learn more about what happens when staph bacteria colonies grow to extraordinary numbers. Prior studies had shown a “superantigen” effect. When the bacteria reach a certain threshold, they initiate a defense mechanism against the body’s immune system, targeting key cells involved with immune-related functions, called T-cells.

In their latest study, the investigators exposed a group of rabbits to the staph superantigen. Once in the body, the bacteria created a domino effect of physiologic responses — first targeting fat cells and the immune system, which then triggered an inflammation response and, finally, insulin resistance. When the team took swab samples from four diabetes patients, they found superantigen levels were proportional to those causing diabetes-like symptoms in the rabbits.

Up next for the scientists is developing a way to stop the staph bacteria from colonizing and forming superantigens in the first place, Schlievert says. Most likely it will come in the form of a gel compound containing glycerol monolaurate that kills bacteria on contact. “This compound is already approved by FDA for some uses on people,” he explained.

Also in the works is a vaccine that can inoculate humans against the bacteria’s invasion. Schlievert says the vaccine has achieved success in the lab — protecting 86 of 88 rabbits from the superantigen — and now he has his sights set on pursuing phase 1 safety trials in humans.

According to estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, type 2 diabetes will afflict roughly one in three people by the year 2050. It is already the leading cause of new cases of blindness, kidney failure, and amputations unrelated to accidents or injury.

Source: Vu B, Stach C, Kulhankova, et al. Chronic Superantigen Exposure Induces Systemic Inflammation, Elevated Bloodstream Endotoxin, and Abnormal Glucose Tolerance in Rabbits: Possible Role in Diabetes. mBio. 2015.