UK, Japan Scientists Win Nobel for Stem Cell Breakthroughs

Scientists from Britain and Japan shared a Nobel Prize on Monday for the discovery that adult cells can be transformed back into embryo-like stem cells that may one day regrow tissue in damaged brains, hearts or other organs.

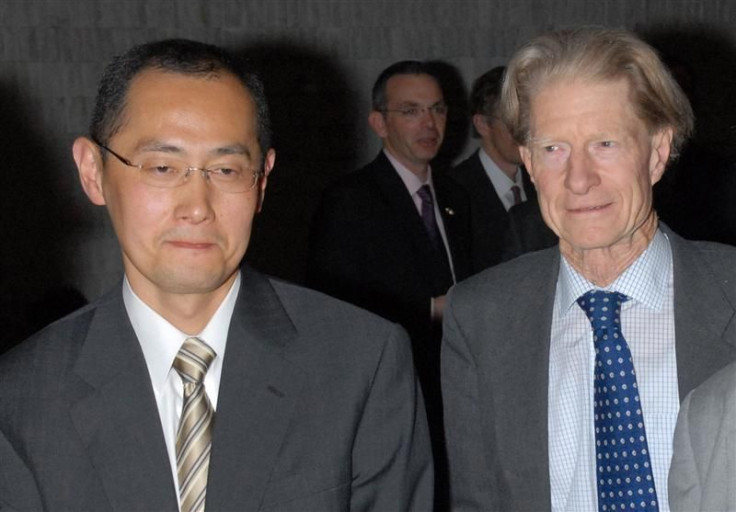

John Gurdon, 79, of the Gurdon Institute in Cambridge, Britain and Shinya Yamanaka, 50, of Kyoto University in Japan, discovered ways to create tissue that would act like embryonic cells, without the need to harvest embryos.

They share the $1.2 million Nobel Prize for Medicine, for work Gurdon began 50 years ago and Yamanaka capped with a 2006 experiment that transformed the field of "regenerative medicine" - the field of curing disease by regrowing healthy tissue.

"These groundbreaking discoveries have completely changed our view of the development and specialization of cells," the Nobel Assembly at Stockholm's Karolinska Institute said.

All of the body's tissue starts as stem cells, before developing into skin, blood, nerves, muscle and bone. The big hope for stem cells is that they can be used to replace damaged tissue in everything from spinal cord injuries to Parkinson's disease.

Scientists once thought it was impossible to turn adult tissue back into stem cells, which meant that new stem cells could only be created by harvesting embryos - a practice that raised ethical qualms in some countries and also means that implanted cells might be rejected by the body.

In 1958, Gurdon was the first scientist to clone an animal, producing a healthy tadpole from the egg of a frog with DNA from another tadpole's intestinal cell. That showed developed cells still carry the information needed to make every cell in the body, decades before other scientists made headlines around the world by cloning the first mammal, Dolly the sheep.

More than 40 years later, Yamanaka produced mouse stem cells from adult mouse skin cells, by inserting a few genes. His breakthrough effectively showed that the development that takes place in adult tissue could be reversed, turning adult cells back into cells that behave like embryos. The new stem cells are known as "induced pluripotency stem cells", or iPS cells.

"The eventual aim is to provide replacement cells of all kinds," Gurdon's Institute explains on its website.

"We would like to be able to find a way of obtaining spare heart or brain cells from skin or blood cells. The important point is that the replacement cells need to be from the same individual, to avoid problems of rejection and hence of the need for immunosuppression."

The science is still in its early stages, and among important concerns is the fear that iPS cells could grow out of control and develop into tumors.

Nevertheless, in the six years since Yamanaka published his findings the discoveries have already produced dramatic advances in medical research, with none of the political and ethical issues raised by embryo harvesting.

"NOT A ONE-WAY STREET"

Thomas Perlmann, Nobel Committee member and professor of Molecular Development Biology at the Karolinska Institute said: "Thanks to these two scientists, we know now that development is not strictly a one-way street."

"There is lot of promise and excitement, and difficult disorders such as neurodegenerative disorders, like perhaps Alzheimer's and, more likely, Parkinson's disease, are very interesting targets."

The techniques are already being used to grow specialized cells in laboratories to study disease, the chairman of the awards committee, Urban Lendahl, told Reuters.

"You can't take out a large part of the heart or the brain or so to study this, but now you can take a cell from for example the skin of the patient, reprogram it, return it to a pluripotent state, and then grow it in a laboratory," he said.

"The second thing is for further ahead. If you can grow different cell types from a cell from a human, you might - in theory for now but in future hopefully - be able to return cells where cells have been lost."

Yamanaka's paper has already been cited more than 4,000 times in other scientists' work. He has compared research to running marathons, and ran one in just over four hours in March to raise money for his lab.

In a news conference in Japan, he thanked his team of young researchers: "My joy is very great. But I feel a grave sense of responsibility as well."

Gurdon has spoken of an unlikely career for a young man who loved science but was steered away from it at school. He still keeps a discouraging school report on his office wall.

"I believe he has ideas about becoming a scientist... This is quite ridiculous," his teacher wrote. "It would be a sheer waste of time, both on his part and of those who have to teach him." The young John "will not listen, but will insist on doing his work in his own way."