Urinary Tract Infections In Children Are Often Antibiotic Resistant — Especially If They Live In The Developing World

A new, extensive review released Tuesday, March 15, in The BMJ, confirms that, whatever their faults may be, antibiotic resistant bacteria don’t discriminate by age.

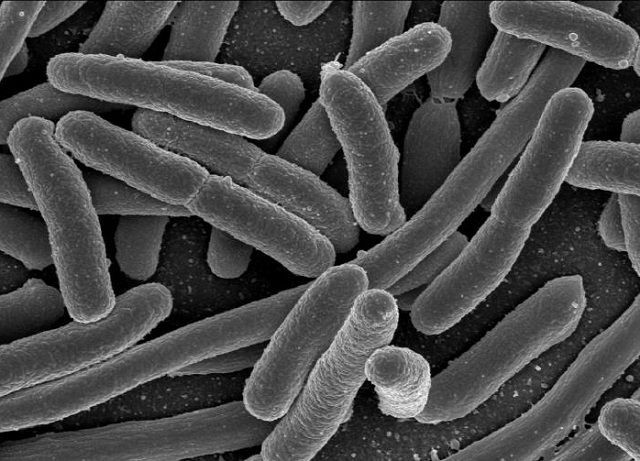

The authors gathered data from 58 previous studies from 26 different countries looking at resistance rates among children aged 0 to 17 with a urinary tract infection, specifically those caused by Escherichia coli . To set up an useful contrast between developed and developing countries, the researchers split the studies between those taken from countries that belong to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), such as the United States, and those that don’t, such as Nigeria.

They found resistance was rampant in all the countries, particularly to first-line antibiotics like ampicillin, but that it was especially abundant in non-OECD countries. Five studies had measured previous antibiotic exposure, and from these the team determined that, after using an antibiotic, people’s risk of resistance increased for up to six months.

“Prevalence of resistance to commonly prescribed antibiotics in primary care in children with urinary tract infections caused by E. coli is high, particularly in countries outside the OECD, where one possible explanation is the availability of antibiotics over the counter,” the authors wrote. “This could render some antibiotics ineffective as first line treatments for urinary tract infection.”

Specifically, E. coli resistance to ampicillin, a widely used and affordable drug for everything from urinary tract infections to meningitis, was found in 53 percent of the pooled 77,783 samples taken from OECD countries. In the non-OECD samples, that jumped up to an average of 79.8 percent. Some nations, including Nigeria and Ghana, had 100 percent of their samples display resistance. For co-amoxiclav, a type of penicillin combined with a booster, the rates between the two groups of countries were 8.2 percent versus a whopping 60.3 percent. For ciprofloxacin, it was 2.1 percent compared to 26.8 percent.

Noting that many health organizations such as the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend antibiotics only be used for a particular germ if its local resistance rate is below 20 percent, the researchers caution their findings may call for a drastic overhaul of urinary tract infection treatment everywhere. Indeed, none of the first-line antibiotics, save nitrofurantoin, held up to that watermark in non-OECD countries. Nitrofurantoin also had the lowest resistance rate in OECD countries, at 1.3 percent, indicating its continued utility there as well. The drug is almost exclusively used to treat the condition, one of the most common bacterial infections in children and most often caused by E. coli.

These rates of E.coli resistance, troubling as they are, do roughly match up with those seen in adult urinary tract infections. Children under the age of 5 did appear to have slightly higher rates, possibly because of more exposure to antibiotics in general.

The researchers speculated there were other reasons aside from over-the-counter antibiotic use for the disparity in resistance rates between the two groups of countries. For instance, non-OECD nations likely have weaker health care infrastructure, meaning doctors and patients alike are less likely to monitor antibiotic use carefully. Similarly, infections or injuries that would be manageable elsewhere spiral out of control more often, leading to a greater use of antibiotics to prevent death.

The other main finding, that recent antibiotic use can promote more resistance down the line, may demand a similarly broad change in how we prescribe antibiotics. “Primary care clinicians will probably need to get used to taking an ‘antibiotic history’ before prescribing for common bacterial infections,” wrote Professor Grant Russell of the School of Primary Health Care at Monash University in an accompanying editorial. “A parent’s claim that ‘antibiotic x always works for my child’ might need to be balanced with the notion that ‘if antibiotic x was used in the last six months, there’s a good chance that it’s not going to work as well if used again.’”

Source: Bryce A, Hay A, Lane I, et al. Global prevalence of antibiotic resistance in paediatric urinary tract infections caused by Escherichia coli and association with routine use of antibiotics in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis. The BMJ. 2016.