Virtual Reality Helps Whites Empathize With Blacks; Could End Racial, Gender, And Religious Biases

The deaths and aftermath of Michael Brown and Eric Garner have exposed a stark divide in racial attitudes across the country. As shown by a Bloomberg poll last week, Americans not only believe that race relations are worsening but they’re also relatively split down the black/white line with whether the deaths were justified by the police officers — more so with Brown’s death than Garner’s. Here’s the problem: People in general are more empathetic toward whites than blacks; they disregard blacks’ pain. And the only way to build that empathy is to put whites in blacks’ shoes, but how?

A new study from the Royal Holloway University of London and the University of Barcelona shows what initial steps toward this understanding could look like. With virtual reality, researchers were able to create illusions in which white participants were in the body of someone with darker skin. In doing so, they tapped into participants’ implicit biases, and developed a sense of empathy, “intention understanding,” and emotion recognition. In other words, by having participants identify themselves as the other person, they created perceptions of similarity, which in turn made participants more inclined to empathize with blacks — treat others the way you’d want to be treated, they say.

“Our findings are important as they motivate a new research area into how self-identity is constructed and how boundaries between ‘in-groups’ and ‘out-groups’ might be altered,” said Professor Manos Taskiris, of the Department of Psychology at Royal Holloway, in a press release. “More importantly though, from a societal point of view, our methods and findings might help us understand how to approach phenomena such as racism, religious hatred, and gender inequality discrimination.”

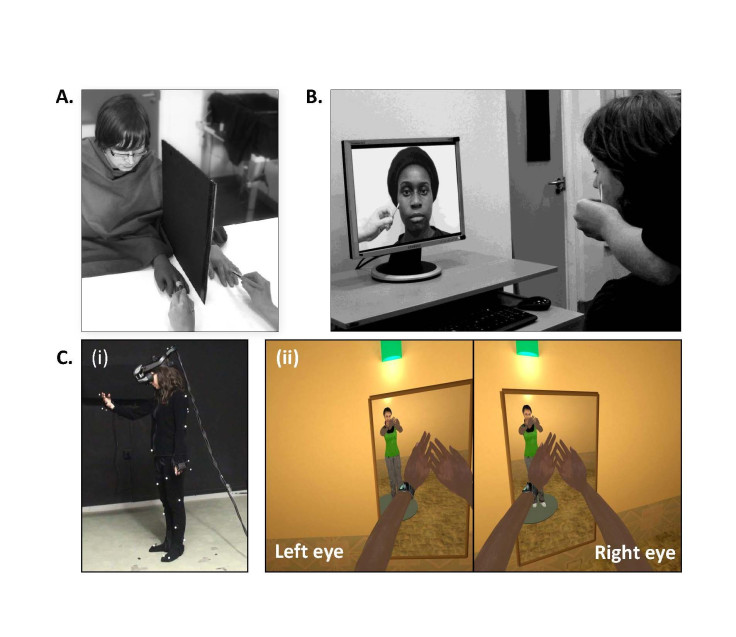

The researchers used various tests to trick participants’ minds. One of them, called the Rubber Hand Illusion, involved participants sitting under a blanket at a table with a dark rubber hand protruding in front of them. Their real hand, meanwhile, was placed to the side, out of view. Both hands were then stroked, among other sensory cues, creating the illusion the hand was theirs. In another similar experiment, called Enfacement Illusion, the same thing was done to the participants’ faces, while watching a black face on a screen. Finally, in a third experiment, participants were exposed to sensory cues while seeing themselves through a virtual reality device as black.

After all three experiments, participants’ implicit attitudes toward blacks were minimized. They were also more likely to report the other person’s face as being more attractive, more physically similar to their own, and they said they were also more likely to conform to the other person’s opinions. This last finding is perhaps the most important, because it’s one thing to empathize with another person’s pain and physical feelings, but to have long-lasting effects that stimulate change in social attitudes is something the researchers acknowledge is still unclear.

With about 40 percent of white Americans surrounded exclusively by friends of their own race, becoming exposed to people of other races could be the best way to quell anxieties. It may not even require these types of experiments. A study from last week found that sending gay canvassers into strongly anti-gay neighborhoods to talk to residents for about 20 minutes about marriage equality, and why it mattered, was effective in changing their attitudes about gays even nine months later. If exposing these anti-gay residents to gay people and their stories could change perception, surely exposing whites to blacks and their stories could as well.

Source: Maister L, Slater M, Sanchez-Vivez M, Tsakiris M. Changing bodies changes minds: owning another body affects social cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2014.