What Is Midazolam: Why Are Doctors Worried The Lethal Injection Drug Won't Sedate Death Row Inmates?

Not to be lost in the shuffle of broad-spanning Supreme Court decisions this past week is one involving the process of lethal injection.

As NPR reported, earlier today the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 to uphold the use of the drug midazolam in the lethal injection protocol utilized by states like Oklahoma to execute its prisoners. The merits of the case, Glossip v. Gloss, relied on whether or not the inclusion of midazolam in lethal injections constituted cruel and unusual punishment, which the majority decided it had not.

Yet, in a scorching dissent by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, she criticized the decision as potentially leaving "petitioners exposed to what may well be the chemical equivalent of being burned at the stake." The case had originally been brought to court by four death row inmates in Oklahoma.

But what exactly is midazolam? And why have medical experts been fiercely against its use as a means of execution?

'Rapid Entry'

According to an amicus brief filed by 16 professors of pharmacology this March in Glossip v. Gloss, midazolam has been around since 1976, when it was first synthesized.

Part of a class of drugs known as benzodiazepines, its cousins include alprazolam (Xanax) and diazepam (Valium). And like its brethren, midazolam has primarily been used to treat anxiety, seizures, and insomnia. More pertinently, it’s also used to help render people unconscious prior to surgery.

This works because of the drug’s depressive effect on the central nervous system. It does this by allowing the major inhibitory neurotransmitter of the body, GABA, to better bind to corresponding receptors in the brain, slowing down the electrical activity of neurons as these receptors are opened wide. The more GABA that floods the brain, the slower it functions, to a certain point.

What makes midazolam special among benzodiazepines is the speed with which it can do this, with the brief noting the "rapid entry of midazolam into brain tissue and very rapid onset of activity following intravenous administration." It also means that midazolam doesn't linger in the body for too long.

It’s that efficiency that likely impressed the penal systems of Oklahoma and three other states. In recent years, they’ve decided to turn to midazolam because the supply of drugs previously used in lethal injections — sodium thiopental and pentobarbital — has run dry, due to the refusal of manufacturers to provide them for execution.

But as the amicus brief explains, filed independently and in support of neither party, midazolam is not the cousin of sodium thiopental or pentobarbital. And its subtle differences from the two may indeed constitute a cruel fate for those lethally injected with it.

Ceiling Effect

Sodium thiopental and pentobarbital are barbiturates, which also work to depress the central nervous system. Unlike benzodiazepines, however, which amplify the naturally occurring GABA’s effect on receptors, barbiturates hijack these receptors and leave the gate open for longer periods of time, even in the absence of GABA.

And because the brain only produces a certain amount of GABA at any one time, it’s that distinction that makes barbiturates’ effect on the brain much more potent than benzodiazepines. To think of it in another way, midazolam is the crowbar that helps you open a stubborn window to get inside a house, while barbiturates are the wrecking ball that create a new door for you right on the spot. That destructive potential has led to the decreased use of barbiturates as first line treatments, in favor of benzodiazepines and other less dangerous and addictive drugs, but it does make them perfect candidates for lethally injecting someone to death.

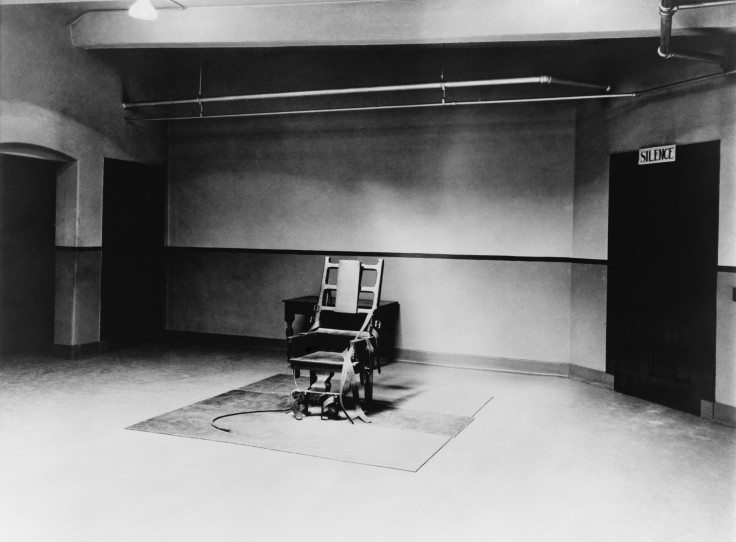

The lethal injection process in Oklahoma actually involves three injections: One to fully sedate the prisoner, another to paralyze them, and the third to actually kill them. Thiopental and pentobarbital are more than capable of consistently accomplishing the first task (barbiturates can reliably send someone into a permanent coma all by their lonesome as a matter of fact). But according to the brief, midazolam simply can’t, no matter how much of it you inject into someone. "[A]s the dose of benzodiazepine increases, the benzodiazepine curve plateaus, reaching a 'ceiling' before general anesthesia can be reached," they wrote.

This is exactly why midazolam is only used by doctors to help sedation along, like the aperitif equivalent of anesthesia. There’s little reason to believe that it alone can completely dull the pain from the remaining injections shot into a person scheduled for death, and several unfortunate examples that demonstrate its inefficiency at doing so (As the Pacific Standard's Nick Walsh noted in 2012, there's been controversy surrounding the use of barbiturates in lethal injections as well, but it was generally about the possibility that those executed have been insufficently dosed, not about these drugs' inablity to produce coma provided a large enough dosage.)

In April 2014, Oklahoma death row inmate Clayton Lockett writhed in pain for nearly an hour and ultimately died of a heart attack after an injection of midazolam failed to sedate him. At the time, that state argued that Lockett’s botched execution was the result of a failure to properly inject him through a suitable vein, and not the drug itself. But other executions involving midazolam have resulted in men like Joseph Wood taking over two hours and 14 extra injections to finally die. Before he expired, Wood apparently gasped for life over 600 times, according to the Arizona Republic’s Michael Kiefer.

Critics have pointed out that the majority of lethal injections using midazolam have gone smoothly, but considering that Oklahoma's protocol also involves paralysis, it’s possible that at least some of the men we’ve sent to their deaths using midazolam suffered immensely along the way, chemically frozen in horror.

'Constitutionally Adequate'

For their part, the Supreme Court justices that voted to allow midazolam to be used in lethal injections focused more on the legal issues surrounding the case rather than the scientific ones.

But in speaking about the clinical evidence presented to the court, Justice Samuel Alito wrote, "[T]he fact that a low dose of midazolam is not the best drug for maintaining unconsciousness during surgery says little about whether a 500-milligram dose of midazolam is constitutionally adequate for purposes of conducting an execution."

As Alito notes, there hasn’t been definitive evidence demonstrating that such a large dose wouldn’t knock someone out long enough for the rest of the injections to kill them, but neither has there been concrete proof showing that it can. Essentially then, future prisoners who are lethally injected will serve as guinea pigs for a drug cocktail that may or may not subject them to literally unspeakable pain in the moments before death.

Without getting into the morality of the death penalty, it feels difficult to see that sort of ignoble end as anything other than cruel and unusual.

Published by Medicaldaily.com