What Is Shingles? Four Things To Know About Painful Chickenpox-Related Disease

Shingles may be a disease that sounds more festive than dangerous, but don’t be fooled.

As Medical Daily’s own Samantha Olson has personally attested, shingles can be an excruciating experience with health consequences that may last for years afterward. But what exactly is shingles and what are some of the most important things we need to know about it? Let’s take a look.

An Old Foe

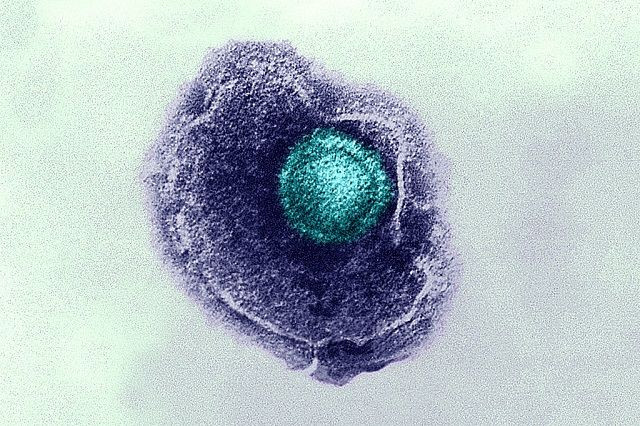

Shingles is caused by the same pathogen responsible for chickenpox, varicella zoster virus (VSV), a cousin of the viruses responsible for both types of herpes.

Though chickenpox is typically a mild, if highly contagious, disease that’s easily defeated by our immune system, the virus itself isn’t completely vanquished. Like a comic book villain, it escapes and hides away in our nerve cells undetected, biding its time for decades. For only broadly understood reasons, such as a weakened immune system, the previously dormant VSV reemerges in about one-third of past chickenpox sufferers and goes on a rampage, often bringing on pain, fever, and a distinctive rash limited to one side of the body that lasts for weeks. Even worse, about twenty percent of these sufferers will likely have yet another episode of shingles in the future.

It’s No Joke

Aside from causing pain that would send the toughest guy into a fetal position (Olson aptly described it as a “dragon living inside my ribcage”), shingles can have far-reaching implications past its initial bout.

In some cases, people will develop a condition called post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN). The virus leaves behind lingering nerve damage, causing affected areas to erupt with pain at the slightest touch. While PHN usually lasts for a few weeks, it’s been known to plague sufferers for years. It’s estimated that upwards of 10 percent of shingles patients will develop PHN, with the risk increasing the older you get.

Elsewhere, other research has shown that shingles can slightly raise the risk of stroke for older adults in the first three weeks following its emergence.

A Vaccine Connection?

Some experts have worried that the chickenpox vaccine will and has increased the risk of developing shingles. But the evidence doesn’t seem to bear that out. In recent years, the rate of shingles cases has climbed, but this increase started happening before the chickenpox vaccine became mandatory for school-age children in 1996.

Because the vaccine uses a live, if weakened, version of VSV, it isn’t impossible for the virus to pull off its disappearing act and later cause shingles. But that possibility is likely much rarer than the chances of someone who naturally came down with chickenpox and would have much more virus circulating in their system. Ultimately, though, it will probably take decades for us to be sure about that.

That doesn’t mean the vaccine hasn’t caused some unintended mishaps. In her article, Olsen raised the possibility, borne out by some research, that people like her — adults who contracted chickenpox right before the vaccination program began in earnest — might be at heightened risk of shingles.

As the theory goes, previously infected children in the past were frequently exposed to the virus from their fellow friends and family, which helped their immune system remember how to defend against it. And children today receive a second booster shot against it in their elementary school years, mimicking that same effect. But for that small slice of adults, they likely only were exposed to the virus once during their initial infection. And as they continue to grow up in a world without chickenpox everywhere, they may be more vulnerable to shingles.

The Future Of Shingles

With the advent of a chickenpox vaccination, though, shingles will likely someday become a relic of the past for most everyone else.

Even if the occasional case does happen, they’ll probably be much less troublesome, according to Dr. William Schaffner, doctor of preventative medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

"Nearly 99 percent of children who receive the vaccine will not get chickenpox at all," Schaffner told Live Science in 2014. "The remaining 1 percent who do get it will get a much milder version of it. Therefore, a vast majority of people receiving the immunization will not develop shingles later in life."

Until then, though, efforts are underway to protect the next incoming generation of still vulnerable senior citizens (though stress and disease can trigger shingles, aging remains the biggest risk factor). In 2006, the FDA approved Zostavax® for adults 60 and older. The one-dose shot has been shown to reduce the risk of shingles by around 50 percent and the risk of PHN by around 60 percent, but quickly drops off in effectiveness after five years.

Though currently the only vaccine on the market, another vaccine by GlaxoSmithKline proved to be 97 percent effective in a Phase 3 randomized clinical trial of over 15,000 participants published last year as well as one published this September. The company plans to file for approval of its vaccine from the FDA by the end of the year.