What Taste Buds Look Like In Action: Scientists Give First Glimpse In Real-Time

To the naked eye, chewing food won’t look like anything special. Just some beige mush that will soon get swallowed. But on a molecular level, a lot is going on. And for the first time, scientists have observed the activation of certain taste cells in real-time.

A study on the findings, published in the journal Scientific Reports, suggests one half of the ever-perplexing taste equation, the physiological component, may be solved. Within each taste bud are many taste cells, which help determine how the taste bud picks up the taste of the food. But uncovering how the brain perceives these sensations to pick up on one taste over another, still remains a mystery.

Research into taste in the last several decades has debunked at least one myth, namely, that the tongue can be divided into five distinct, fenced-in regions for each of the five tastes: bitter, salty, sour, sweet, and umami. In knocking down that misconception, scientists actually raised even more complex questions: If the tongue’s some 2,000 taste buds are localized based on taste, then how are they organized? Are they organized at all?

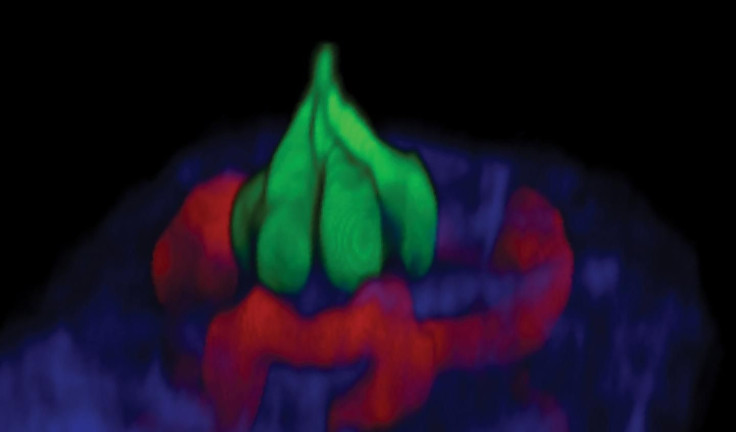

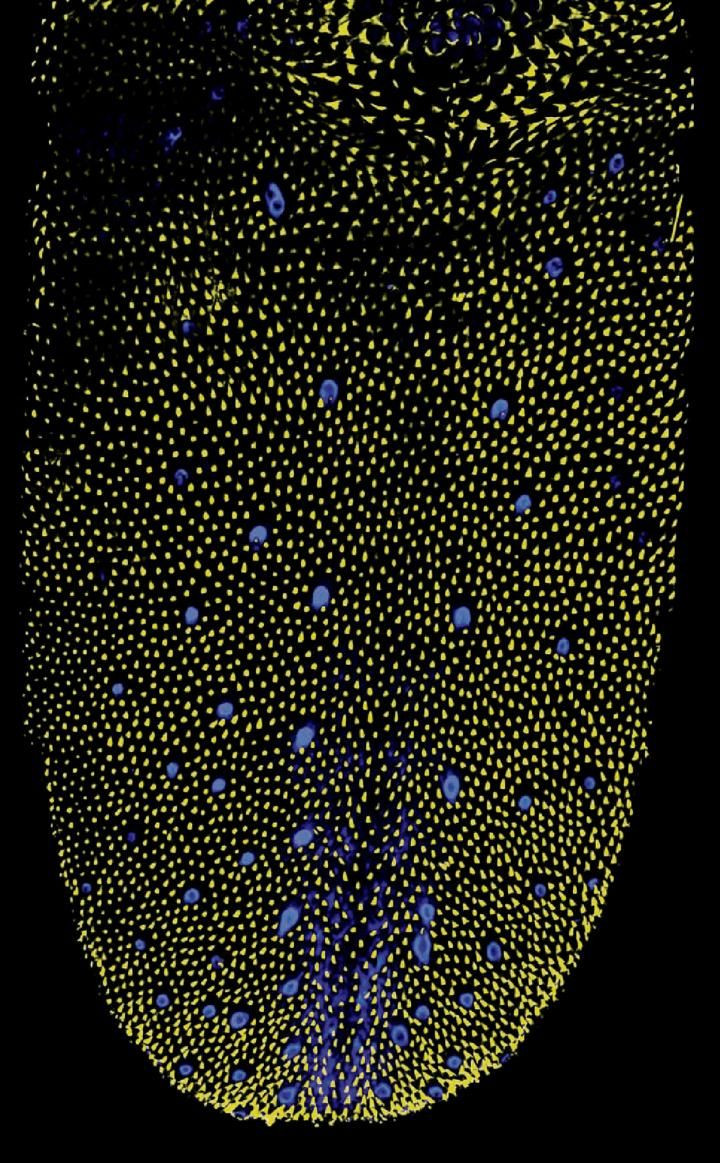

Biomedical engineer Dr. Steve Lee, from the Australia National University, and his colleagues set out to answer those questions by feeding mice various “tastants,” or foods, and observing how the tongue’s taste cells reacted. Using a technique called intravital multiphoton microscopy, they shone an infrared light on each of the mice’s tongues that let them observe the behavior of taste cells and blood vessels as deep as 240 microns beneath the tongue’s surface. Each tongue lit up, or fluoresced, to reveal a raft of information about which cells were activating.

Some of the results came as a surprise, such as the relationship between food molecules and blood composition, said lead author Myunghwan Choi, of Sungkyunkwan University in South Korea. Rather than the taste cells interacting solely with the food itself, there seemed to be an interplay between the taste cells and the blood in the underlying vessels. “We think that tasting might be more complex than we expected,” Choi said in a press release.

Now that they’ve established how taste works on a molecular level, the team is working on designing an experiment to track the perception of taste. With such technology, they could figure out how certain foods become acquired tastes, like broccoli or beer. And they could uncover how to help people with eating disorders, such as food addictions, to control their cravings.

Unfortunately, Lee said, these advances are still years away from being fully realized. “Until we can simultaneously capture both the neurological and physiological events,” he said, “we can't fully unravel the logic behind taste.”

Source: Choi M, Lee W, Yun W. Intravital Microscopic Interrogation of Peripheral Taste Sensation. Scientific Reports. 2015.

Published by Medicaldaily.com