When Genome Sequencing Tells Too Much, Doctors May Have To Keep Secrets

Genome sequencing is rapidly being integrated into the practice of medicine thanks to the falling price of sequencing combined with incremental advancements in bioinformatics. But as genomic information becomes more readily available to both doctors and patients, the explosion of personal data has spurred ethical discussions about what to do with the results, especially when inadvertent and unsettling discoveries are unearthed.

DNA may give us answers to questions we have not asked, and if the future of genomic testing comes to sequencing children at birth like experts believe, a child’s fate could unravel for parents within minutes of their birth.

“One could imagine a future where a child’s genome is sequenced at birth, it goes into their electronic health record and every time they go to see their doctor, their doctor looks up what their sequence is and looks for what kind of medications to give them, diseases to look for, and so forth,” said Dr. Eric Green, director of the Human Genome Research Institute (HGRI). “But it raises a whole host of ethical issues. The ethical questions are very different for sequencing a healthy newborn as opposed to an acutely ill one.”

Researchers at HGRI are already sequencing the genomes of newborn babies to explore possible ramifications before they’re played out in real time through a project nicknamed “NSight,” or Newborn Sequencing In Genomic Medicine and Public Health. The ongoing research project will advance clinical understanding through specific disorder screening and assess the ethical, legal, and social implications of implementing at-birth genomic sequencing.

The Newborn Dilemma

Green says it’s likely to become common practice to sequence a newborn’s genome. Sequencing a healthy child would serve as a form of screening, while sequencing an acutely ill newborn suffering from a mysterious disease will serve as an in-depth diagnostic tool to search for answers within their DNA.

Every year, an estimated 7.9 million children worldwide are born with a birth defect of genetic or partially genetic origin, according to the March of Dimes’ Global Report on Birth Defects. Children can be born with any one of the 3,500 genetic diseases, making it a particularly difficult problem for physicians because it can take months or even years to solve. Newborns age congenitally fragile from birth, making their chances of recovering less than likely compared to an adult.

Babies placed into the neonatal intensive care unit at Kansas’ Children’s Mercy Hospital — because of a mysterious and undiagnosed condition — rely on the success of genomic testing to survive. For the last three years, Dr. Stephen Kingsmore, director of the Hospital’s Center for Pediatric Genomic Medicine, has been sequencing the genetic information of newborns suffering from an occult disease using a unique computer-operated method.

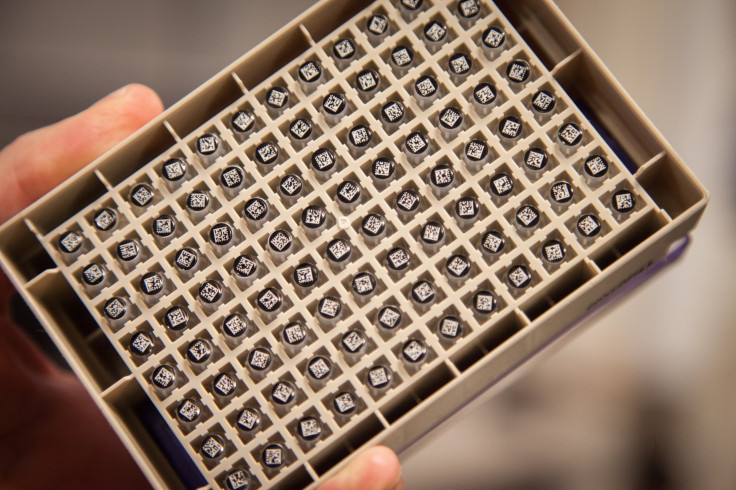

With one drop of blood, Kingsmore’s team of physicians, scientists, and pathologists are able to instantly decode the genome of a newborn. Once the sequence is uploaded onto their system, doctors enter in the baby’s symptoms, allowing the computer to search their genome for the possible genetic culprit causing the disease.

Currently, no other children’s hospital in the world provides this novel neonatal diagnostic service. The method, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, provides doctors with enough genetic clues into what could have gone wrong within 24 hours of testing. A third of the time Kingsmore can definitively identify the disease in a child’s case. But using sequencing to identify the genetic cause of a disease is different than routine screening of a seemingly healthy baby at birth.

“Nearly every child in America is genetically tested for two to three dozen diseases at birth,” Green said. “The question that’s being asked is, ‘Why don’t we just sequence their genome?’” If we did, he says, we could know whether or not “they have two to four thousand genetic diseases instead of just two dozen.”

However, researchers are taking the blindfold off when they sequence a healthy newborn, and what they see has the potential to disrupt the child and family’s life. At such an early point in our genetic knowledge, it’s difficult to ascertain how a particular gene variant associated with disease will affect the child’s life, if at all. It’s also unclear if the gene puts them at risk for developing a disease that may be treatable or even curable in 20 or 30 years. On the other hand, routine screening has the potential to detect diseases early, which could save their life.

If doctors do find a disease-related gene in a newborn's sequence that indicates a chance of the future onset of disease like Alzheimer’s, it’s not a guarantee they will go on to develop the disease. Green predicts that because they’ve only had 12 years to analyze the genome sequence, it could take a couple of generations to fully understand genetic risk factors and know which genes will consequently lead to developing a disease.

“It’s not that we’re inept,” Green said. “It’s that we just don’t know. We’re still learning. Our knowledge hasn’t caught up with our technological innovation. You’ve got six billion letters in your genome and we’re only 10 percent of the way to understanding what all of those letters mean.”

Divulging Discoveries to Patients

These ethical questions are already coming up in clinical settings, and coming up with answers is becoming increasingly relevant to the next generation of medicine. For example, a cancer patient, who is having their genome sequenced to see which drug treatments will prove most effective, may unexpectedly learn that they are strongly susceptible to an early-onset neurological disorder like Alzheimer’s disease — that is, if their doctor tells them. Researchers and doctors have been trying to figure out how to handle the unsettling discoveries that come from incidental findings for years.

“How do you go about counseling them with information when it’s so unexpected?” asked Dr. Richard Sharp, director of the Biomedical Ethics program at Mayo Clinic. From a clinical point of view, he says it is one of the most pressing issues for doctors to grapple with when it comes to patient care. “The question isn’t how best to have the conversation, but rather is this something they want to know?”

In December 2013, the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues finally published a set of recommendations on how to handles incidental findings with major emphasis on genetic testing. The report advises doctors and researchers to discuss the possibility of incidental findings with their patients before they undergo testing, and also conduct studies to better understand the potential seriousness of test outcomes. It gives patients the opportunity to decide in advance whether or not they want to be told about any unexpected discoveries.

That same year, the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) said stumbling upon unexpected disease-related genes wouldn’t be enough. Instead, every time a lab conducts genome sequencing for a particular disease, doctors should take it a step further by ordering tests for several dozen other specific disease markers. Doctors should then report any incidental findings when a gene is clearly linked to disease. The recommendations include searching for BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants, two genes that are known to increase the risk for breast and ovarian cancer.

Controversy ensued when the ACMG argued incidental findings should be disclosed, even when the patient doesn’t want the information, or if they're a child. Advocating for transparency becomes especially tricky when the patient is a child who’s not old enough to fully understand the findings or to consent to sequencing in the first place.

“We do identify tragic things we have to share with children all the time — rare cancers, chronic diseases that are diagnosed — and we have to identify the ways in which we should share that information with children,” Sharp said. “If the child is sequenced at birth and the information is already there, there will be all of these complexities about what point do you start the conversation? There’s going to be a real need for a national level discussion on when and how to breach the conversation with a child.”

In the case of a parent requesting to actively seek out early-onset markers for predispositions of diseases like breast cancer for their child, Sharp said a responsible physician would deny them the sequence unless that parent was able to provide a valid reason. The medical community generally advises against it because it would force them to navigate through new territory fraught with unpredictable challenges.

“We’re going to have to find the right ways to curb our enthusiasm for genetic testing,” Sharp said, “and really limit genetic testing only to situations that we have reason to suspect are going to be useful to the patient’s well being. Excessive testing can cause distress, raise cost, and generate information that ultimately doesn’t have any clinical utility.”

Doctors can restrict patients from ordering certain tests, but ultimately the ethicality of reporting incidental findings is left up to the patient who has the right to deny learning about their possible risk factor for disease. Moral puzzles will inevitably intensify to become more difficult, forcing the medical community to figure out how to prepare for the onslaught of information sequencing will unleash as it becomes more common.

“These are the kinds of situations that come up pretty routinely already,” Sharp said, “and we’re going to have to deal with it more often as more and more people are sequenced.”

Published by Medicaldaily.com