Where Am I? When Processing A Scene, We Categorize The Most Basic Characteristics First, Then The Details

Our brain is an amazing tool, wired to help us decipher the world around us in such a way that promotes our safety, while also enabling higher learning. When we encounter a scene, we have the ability to take the stimuli we’re surrounded by, and categorize them in a way that helps us better understand where we are and what’s happening. In more primitive times, this categorization helped us to distinguish danger before it was too late. Psychologists used to believe this categorization process worked by prioritizing certain stimuli over others, but now, researchers are finding this process may be far simpler. It turns out that when we categorize a scene, our brains initially group stimuli based on the easiest way to distinguish them.

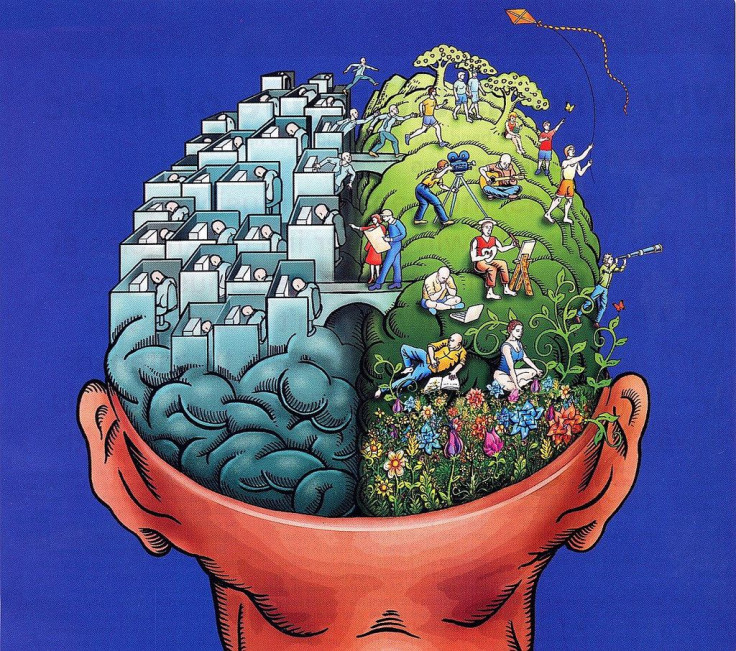

Looking at a scene, there are many things we can take away from it; is it a natural landscape, a manmade one, a forest or a beach, a face or not a face? Previous research has found that when we look at our surroundings, certain levels of categorization happen sooner than others, leading many researchers to believe that the brain establishes priorities. “The superordinate advantage,” suggests that our brains will establish the global characteristics of a scene before its details. For example, we are more likely to decipher whether we’re indoors or outdoors first, before acknowledging details, like whether it’s a kitchen or bedroom.

But Thomas Serre, assistant professor of cognitive, linguistic, and psychological sciences at Brown University feels we are overcomplicating the matter of categorization. “Whatever is happening in the visual system might not be as sophisticated as we thought,” he said in a recent press release.

To prove that “the superordinate advantage” is not always the natural way of categorizing a scene, Serre, along with co-authors Imri Sofer and Sébastien Crouzet, set up a prediction that we first categorize a scene based on “discriminability,” a measurement that describes how easy it is to distinguish between stimuli in a scene. For instance, when looking at a scene, do you first notice that you are outside or that you are in a desert?

In order to measure discriminability within their study, the researchers created a computational model, or algorithm, which they trained by exposing it to a large variety of natural scenes. Once the algorithm had been trained in these scenes, it was then taught categorization tasks. For this given experiment, the algorithm calculated how close each given scene was to a boundary, or a 50/50 shot of being one thing or the other, in this case either man-made or natural. The greater the distance from the boundary (how easily it could be deciphered as man-made or natural), the higher the discriminability score.

The researchers then brought in a small group of participants to test their new algorithm. This part of their research consisted of two experiments. In the first, eight people were exposed to hundreds of trials in which they looked at different scenes and were told to make the distinction between man-made or natural by pressing a button. Ultimately, they found that the higher the discriminability score, the quicker and more accurately participants were able to categorize the scene.

For the second experiment, the researchers asked: When taking discriminability into account, will the superordinate advantage theory still hold up? To test this, the researchers brought in 24 new participants, and exposed them to images that had to be grouped through a superordinate categorization (man-made vs. natural) or a basic categorization (desert vs. beach). Half of the participants were then given images with greater discriminability for superordinate categorizations, while the other was presented with easier-to-decipher, basic characterizations.

Researchers guessed that if the superordinate advantage was truly how our brains operated, participants would be able to decipher superordinate characteristics quicker than basic ones. However, they observed that when basic categorizations were easier, participants were able to make these distinctions faster and more accurately. Therefore, they concluded that the “basic advantage,” or the ability to decipher the most obvious distinctions, was how our brains processed a scene.

However, they said this doesn’t mean the superordinate advantage doesn’t play a part in the brain’s categorization methods; if superordinate categorization is easier, then we will distinguish it first. “The mere fact that it is possible to reverse [the superordinate advantage], shows that it is not a sequential type of process,” Serre said, adding that it’s possible there still exists a hierarchy of priorities, which further research will uncover.

Source: Serre T, Sofer I, Crouzet S. Explaining the Timing of Natural Scene Understanding with a Computational Model of Perceptual Categorization. PLOS Computational Biology. 2015.