This Is Your Brain On Cocaine: Dopamine Buildup Excites Brain's Reward Center, But At What Price?

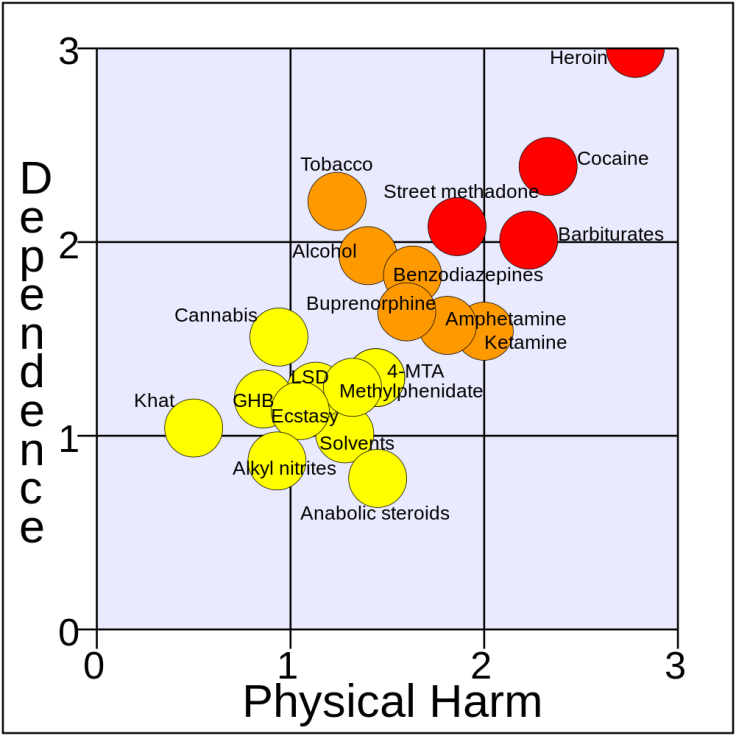

Dr. David Nutt, the Edmond J. Safra professor of neuropsychopharmacology at Imperial College London, caused something of a stir in the scientific community when he in 2007 proposed a definitive “rational scale” for assessing the harm and addiction potential of various substances. Here’s what he published in The Lancet:

Cocaine, as you can see, has been placed far off in the deep end together with heroin. Initially, some questioned this decision. But it would appear that the whole world has since been on a crusade to prove Nutt right.

In the U.S. alone, cocaine abuse is the cause of 5,000 deaths and nearly half a million hospitalizations every year. The drug, which is derived from the leaves of the coca bush, is typically snorted, smoked, or rubbed against mucous tissue for a short high that users describe in terms of unbridled euphoria. Official estimates indicate that 15 percent of the population has tried the drug, with 6 percent reporting use prior to their senior year of high school.

Cocaine is a versatile killer: Users may develop serious heart problems or intestinal ulcers, suffer a stroke, or just die right there on the spot. The drug is also associated with an array of non-lethal yet chronic problems, such as seizures, headaches, nausea, and kidney problems. So, why do people do it?

Because It Does This To The Brain

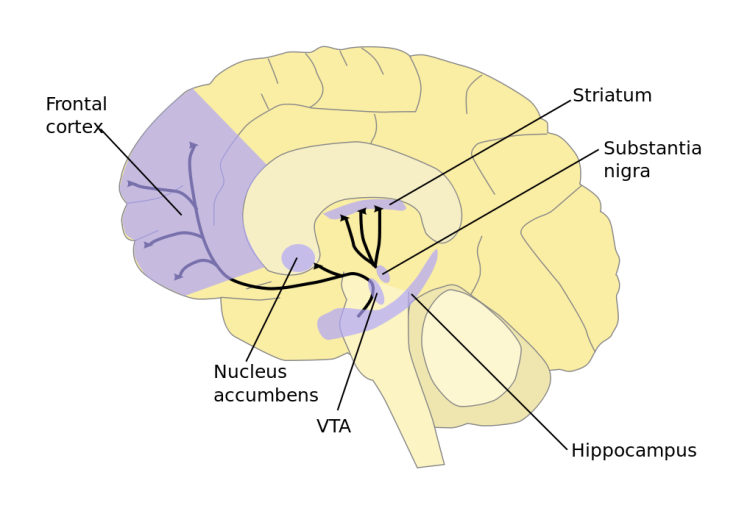

To fully comprehend why cocaine users find it nearly impossible to kick the habit, it is important to have a handle on what cocaine actually does. Luckily, research has led to a pretty clear map of the drug’s mechanism of action inside the body. It all starts in a brain region called the ventral tegmental area.

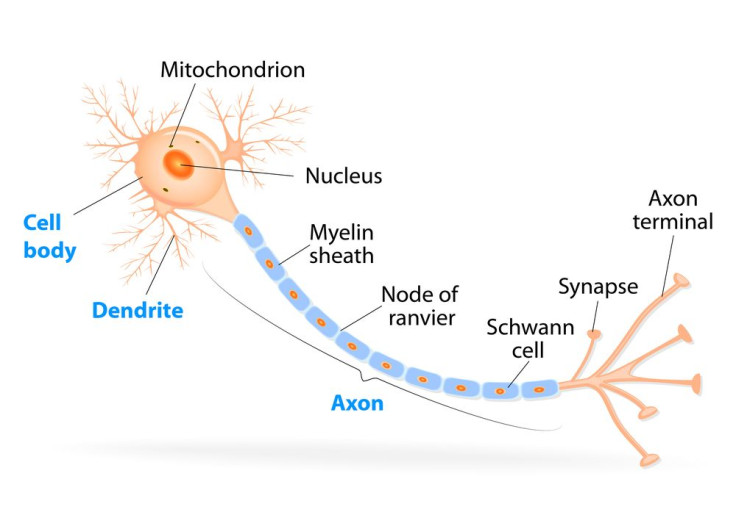

From here, nerve fibers extend to the nucleus accumbens, which plays an important role in the brain’s reward system. Studies with animals have found that this area becomes more active in response to higher levels of dopamine, a brain chemical that is released by rewards. In order to activate the nucleus accumbens, this chemical, or neurotransmitter, must flow along the so-called synapses — connective structures between neurons.

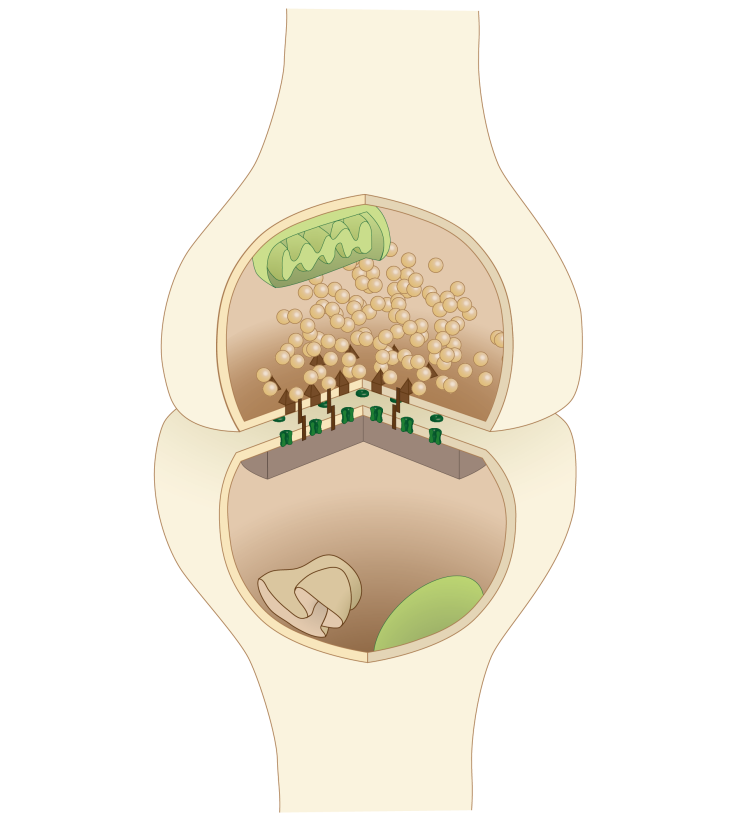

Normally, this is carried out according to a neat set of rules. First, the reward stimulus is recognized; second, dopamine (the tan dots) is released across synapses; third, specialized receptors (the dark green cylinders) receive and interpret the transmission; and finally, dopamine is removed from the synapse to be recycled and used again.

When you throw cocaine into the mix, things get weird right away. During the high, the protein transporters tasked with carting off dopamine for recycling are momentarily taken out of commission, allowing a steady buildup of the neurotransmitter in the synaptic structure. This coaxes the nucleus accumbens into a state of activity that is, according to user accounts, pretty great.

“It's like a hurricane blast of pure white pleasure,” said one user involved in a 1999 study of the psychoactive drug.

However, the same user is quick to point out that the fun never lasts. Once the euphoria subsides, the opposite feeling takes root. “It's the most horrible depression I ever got. The only thing to do is do more coke, but it doesn't help… ”

Other immediate side effects of dependence include fatigue, agitation, and problems sleeping. Users have also reported psychotic episodes, delirium, sexual dysfunction, and mood swings. Usually, the easiest way to quell these withdrawal symptoms is to snort more cocaine — and as tolerance develops, each hit becomes more dangerous than the one before.