This Eye Exam Could Detect Alzheimer’s Early Signs

It's always been difficult for doctors to make a conclusive diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in its early stages. Unfortunately, Alzheimer's disease usually isn't diagnosed in the early stages, even in people that visit their doctors complaining of memory problems. One reason is people and their families generally underreport the symptoms.

This is one reason there is still no single definitive test to diagnose Alzheimer's disease despite decades of research. This means detecting Alzheimer's is an equally tough job. An Alzheimer's eye test will be an easy and inexpensive way to spot early signs of the disease but no such test currently exists for the most common cause of dementia.

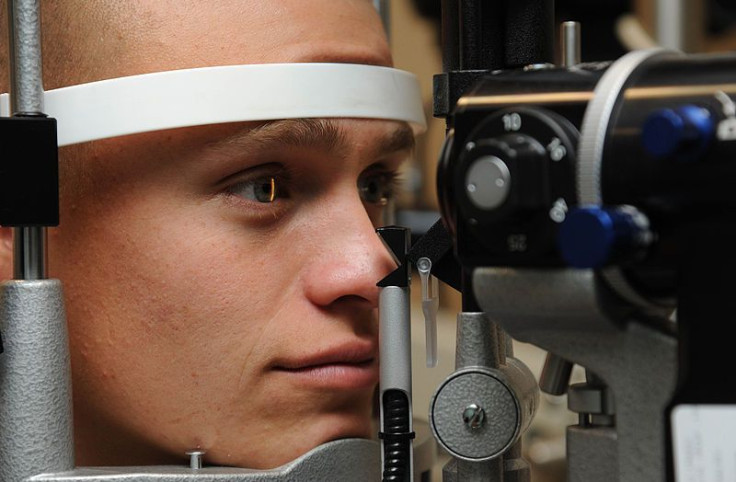

A simple eye exam, however, might make it easier to detect Alzheimer’s disease many years before severe clinical symptoms appear. These retinal screening tests are about to undergo a $5 million clinical trial sponsored by the University of Rhode Island (URI), Butler Hospital in Providence and BayCare Health System, a system of 15 hospitals and other centers in central Florida.

The hope is that retinal screening tests might someday be administered by optometrists and ophthalmologists to detect Alzheimer's in its early stages. Retinal screening tests are also incredibly cheaper than positron-emission tomography (PET) scans used to detect the buildup of amyloid plaques in the brain associated with Alzheimer’s before symptoms appear.

PET scans, however, cost thousands of dollars and aren't normally covered by most insurance plans. Physicians also use invasive spinal taps to help diagnose Alzheimer's but a diagnosis usually isn't confirmed until signs of the disease are found in the deceased patient's brain.

“When our study is completed, we want to make the technology available so that optometrists and ophthalmologists could screen for the retinal biomarkers we believe are associated with Alzheimer’s disease and watch them over time,” Peter Snyder, URI’s vice president for research and economic development, professor of biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences and a principal investigator in the study, said.

“If clinicians see changes, they could refer their patients to specialists early on,” Snyder noted. “We believe this could significantly lower the cost of testing. We may then identify more people in the very earliest stage of the disease, and our drug therapies are likely to be more effective at that point and before decades of slow disease progression.”

The study will see researchers enroll 330 volunteers, ages 55 to 80 “ranging from very healthy and low-risk adults, to persons with concerns about their memory, as well as patients with mild Alzheimer’s disease.”

Volunteers will be examined at four different times over a three years span. Each study visit will include an eye exam, a medical history discussion, some tests of how people think and how well they remember new information, the retinal imaging very much like the kind done at the eye doctor’s office and measures of mood, walking and balancing, sleep habits and other types of medical information.

The URI effort partners that of billionaire Bill Gates, who, in July 2019, announced a $30 million investment to develop a reliable and affordable test for Alzheimer's.

"We need a better way of diagnosing Alzheimer's -- like a simple blood test or eye exam -- before we're able to slow the progression of the disease," Gates said in announcing the investment.