Scientists Literally "Squeeze" the Cancer out of Malignant Breast Cells

"Squeezing" stops malignant breast cancer cells from spreading and turns them back into healthy cells, according to new research revealing, for the first time, that simple mechanical forces alone can revert and stop out-of-control growth of cancer cells.

More importantly, scientists found that this transformation can happen even if the genetic mutations responsible for the cancer remain, setting up a fight between nature and nurture in determining a cell's fate.

Scientists presenting the latest findings Dec. 17 at the annual meeting of the American Society for Cell Biology in San Francisco said that "tissue organization is sensitive to mechanical inputs from the environment" during the beginning stages of a cell's growth and development.

"An early signal, in the form of compression, appears to get these malignant cells back on the right track," researcher Daniel Fletcher, professor of bioengineering at UC Berkeley said in a statement.

Although researchers have traditionally focused on genetic mutations within the cell from studying cancer development, recent studies have shown that malignant cells do not always develop into tumors, and that the fates of these cells depend on how they interact with their surrounding microenvironment.

While previous studies found that the manipulation of a cell's environment through the introduction of biochemical inhibitors could control malignant mammary cells into behaving normally, the latest research takes a step forward by introducing the concept of mechanical rather than chemical influences on cancer cell growth.

"People have known for centuries that physical force can influence our bodies," co-researcher Gautham Venugopalan said in a statement.

"When we lift weights, our muscles get bigger. The force of gravity is essential to keeping our bones strong. Here we show that physical force can play a role in the growth - and reversion - of cancer cells," Venugopalan explained.

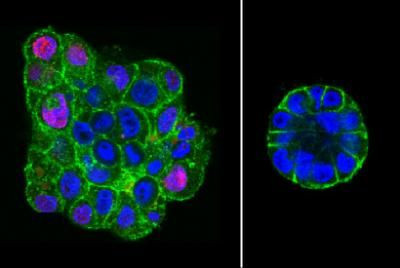

Researchers grew malignant breast epithelial cells in a gelatin-like substance that had been injected into bendable silicone chambers, which allowed them to apply a compressive force in the first stages of cell development. They found that that when compressed, malignant cells grew into more organized and health looking cells that looked like normal structures over time compared.

Furthermore, the findings show that even after compressive force had been removed, the previously compressed malignant cells stopped growing once the breast tissue structure was formed.

"Malignant cells have not completely forgotten how to be healthy; they just need the right cues to guide them back into a healthy growth pattern," Venugopalan explained.

In an additional experiment, researchers looked at the effects of a drug that blocks E-cadherin, a protein that helps cells adhere to their neighbors.

They found that when the drug was added to the cell, despite being physically compressed, the malignant cells returned to their disorganized, cancerous appearance. Researchers said that the effects of the E-cadherin-blocking drug demonstrate the importance of cell-to-cell communication in organized structure formation.

While the latest findings suggest that simple physical force has the power to stall cancer growth, researchers stress that they are not proposing that compression bras be used as a treatment for breast cancer.

"Compression, in and of itself, is not likely to be a therapy," Fletcher explained. "But this does give us new clues to track down the molecules and structures that could eventually be targeted for therapies."

Published by Medicaldaily.com